Bookshelf | Spalding Library | Mormon Classics | Newspapers | History Vault

|

Francesco S. Clavigero (1721-1787) History of Mexico, Vol. II Richmond: Wm. Prichard, 1806 |

|

Acosta's Natural & Moral History (1604) | Southey's Madoc (1805) | Robertson (1812 ed)

Von Humboldt's Researches (1814) | Del Rio's Ruins (1822) | View of the Hebrews (1823)

(this web-page is under construction)

|

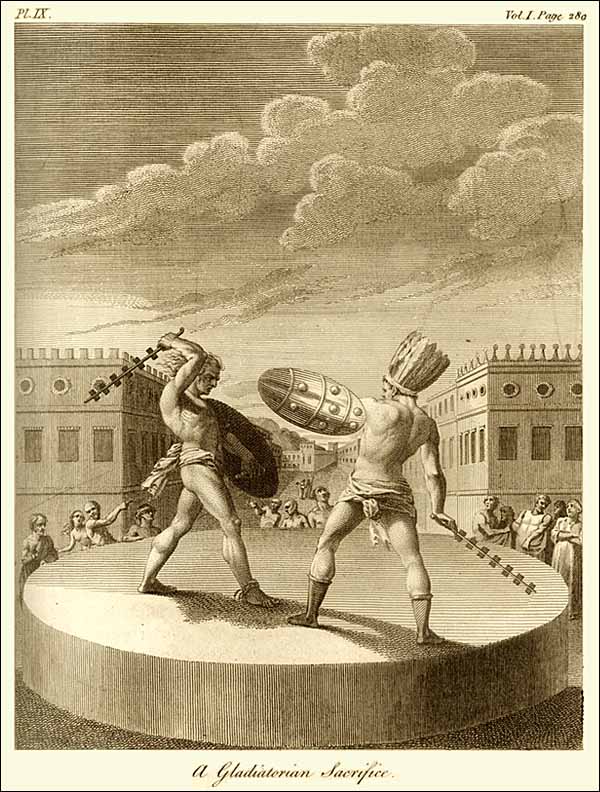

C O N T E N T S OF VOLUME II. __________ BOOK VI. 1 Religious system of the Mexicans 6 The gods of Providence and of heaven 9 The deification of the sun and the moon 11 The god of air 15 The gods of mountains, water, fire, earth, night, and hell 18 The gods of war 22 The gods of commerce, hunting, fishing, &c. 26 Their idols, and the manner of worshipping their gods 27 Transformations 28 The greater temple of Mexico 33 Buildings annexed to the greater temple 36 Other temples 40 Revenues of the temples 40 Number and different ranks of the priests 43 The employments, dress, and life of the priests 46 The priestesses 48 Different religious orders 50 Common sacrifices of human victims 54 The gladiatorian sacrifice 55 The number of sacrifices uncertain 58 Inhuman sacrifices in Quauhtitlan 59 Austerities and falling of the Mexicans 63 Remarkable acts of penitence of the Tlascalans iv CONTENTS. 66 Divination 66 Figures of the century, the year and month 68 Years and months of the Chiapanese 69 Festivals of the four first months 71 Grand festival of the god Tezcatlipoca 75 Grand festival of Huitzilopochtli 78 Festivals of the sixth, seventh, eighth, and ninth months 82 Festivals of the tenth, eleventh, twelfth, and thirteenth months 86 Festivals of the five last months 92 Secular festival 94 Rites observed at the birth of children 98 Nuptial rites 103 Funeral rites 108 Their sepulchres BOOK VII. 111 Education of the Mexican youth113 Explanation of the seven Mexican paintings on Education 116 The exhortations of a Mexican to his son 119 Exhortations of a Mexican mother to her daughter 122 Public schools and seminaries 125 Laws in the election of a king 127 The pomp and ceremonies at the proclamation and unction of the king 129 The coronation, crown, dress, and other insignia of royalty 130 Prerogatives of the crown 132 The royal council and officers of the court 133 Ambassadors 134 Couriers, or posts 136 The nobility and rights of succession 138 Division of the lands, and titles of possession and property 141 The tributes and taxes laid on the subjects of the crown 145 Magistrates of Mexico and Acolhuacan 148 Penal laws 154 Laws concerning slaves 157 Laws of other countries of Anahuac 158 Punishments and prisons 159 Officers of war and military orders CONTENTS. v 162 The military dress of the king 162 The arms of the Mexicans 166 Standards and martial music 168 The mode of declaring and carrying on war 172 Fortifications 176 Floating fields and gardens of the Mexican lake 177 Manner of cultivating the earth 179 Threshing-floors and granaries 180 Kitchen and other gardens and woods 182 Plants mod cultivated by the Mexicans 183 Animals bred by the Mexicans 184 Chase of the Mexicans 187 Fishing 188 Commerce 191 Money 192 Regulations of the market 193 Customs of the merchants in their journeys 194 Roads, houses for travellers, vessels, and bridges 196 Men who carried burdens 197 Mexican language 202 Eloquence and poetry 204 Mexican theatre 207 Music 208 Dancing 211 Games 216 Different kinds of Mexican paintings 219 Cloths and Colours 221 Character of their paintings and mode of representing objects 225 Sculpture 227 Casting of metals 228 Mosaic works 231 Civil architecture 235 Aqueducts and Ways upon the lake 236 Remains of ancient edifices 238 Stone-cutters, engravers, jewellers, and potters 240 Carpenters, weavers, &c. 242 List of the rarities sent by Cortes to Charles V. 244 Knowledge of nature, and use of medicinal simples 247 Oils, ointments, and infusions 247 Blood-letting and baths vi CONTENTS. 248 Temazcalli, or vapour-baths of the Mexicans 250 Surgery 251 Aliment of the Mexicans 256 Wine 258 Dress 259 Ornaments 259 Domestic furniture and employments 262 The use of tobacco 262 Plants used instead of soap BOOK VIII. 265 First voyages of the Spaniards to the coast of Anahuac269 Character of the principal conquerors of Mexico 273 Armament and Voyage of Cortes 274 Victory of the Spaniards in Tabasco 276 Account of the famous Indian Donna Marina 278 Arrival of the armament at the port of Chalchiuhcuecan 283 Montezuma's uneasiness, embassy, and presents to Cortes 286 Present from Montezuma to the Catholic king 288 Embassy from the lord of Chempoalla and its consequences 293 Imprisonment of the royal ministers in Chiahuitztla 295 Confederacy of the Totonacas with the Spaniards 295 Foundation of Vera Cruz 296 New embassies and presents from Montezuma 298 Breaking of the idols of Chempoalla 301 Letters from the armament to the Catholic king 302 Signal conduct of Cortes 303 March of the Spaniards to Tlascala 305 Alteration in the Tlascalans, their resolution concerning the Spaniards 311 War of Tlascala 316 New embassies and presents from Montezuma to Cortes 319 Peace and confederacy of the Tlascalans with the Spaniards 321 Embassy of prince Ixtlilxochitl, and league with the Huexotzincas 322 Submission of Tlascala to the Catholic king 323 Entry of the Spaniards into Tlascala 326 Enmity between the Tlascalans and Cholulans CONTENTS. vii 328 Entry of the Spaniards into Cholula 332 Slaughter committed in Cholula 335 Submission of the Cholulans and Tepeachese 336 New embassy and present from the king of Mexico 337 Revolutions in Totonacapan 339 March of the Spaniards to Tlalmanalco 344 Visit of the king of Tezcuco to Cortes 346 Visit of the princes of Tezcuco, and entry of the Spaniards into that court 347 Entry of the Spaniards into Iztapalapan 349 Entry of the Spaniards into Mexico 349 Reception from the king and nobility BOOK IX. 353 First conference, and new presents from Montezuma357 Visit of Cortes to the king 359 Description of the city of Mexico 362 Effects of Cortes's zeal for religion 364 Imprisonment of Montezuma 371 Life of the king in prison 374 Punishment of the lord of Nauhtlan, and new insults to Montezuma 378 Attempts of the king of Acolhuacan against the Spaniards 381 Imprisonment of that king and other lords 384 Submission of Montezuma and the nobles to the king of Spain 386 First homage of the Mexicans to the crown of Spain 387 Uneasiness of the nobles and new fears of Montezuma 390 Armament of the governor of Cuba against Cortes 394 Victory over Narvaez 396 Slaughter of the nobles and insurrection of the people 401 Skirmishes between the Mexicans and Spaniards 404 Speech of the king to the people, and its effect 407 Terrible engagement in the temple 412 Death of Montezuma, and other lords 417 Defeat of the Spaniards in their retreat 420 Fatiguing March of the Spaniards 421 Famous battle of Otompan 425 Retreat of the Spaniards to Tlascala viii CONTENTS. 426 Election of a king in Mexico 428 Embassy from king Cuitlahuatzin to Tlascala 432 Baptism of the four lords of Tlascala 432 Discontent among the Spaniards 434 War of the Spaniards against the Tepeachese 436 War of Quauhquechollan 439 War of Itzocan 441 War of Xalatzinco, Tecamachalco, and Tochtepec 442 Havoc made by the small-pox. Death of Cuitlahuatzin, and prince Maxixcatzin, and election of Quauhtemotzin 444 Exaltation of prince Coanacotzin, and death of Cuicuitzcatzin |

|

HISTORY OF MEXICO.

111