|

[ 25 ]

SOLUTION.

OF THE

GRAND HISTORICAL PROBLEM

OF THE

POPULATION OF AMERICA.

The injudicious and total destruction of the annals and records of the American nations, has not only proved a most

serious loss to history, but very prejudicial to that religion, whose progress, it was supposed, would thereby have

been accelerated: such unexpected effects are sometimes produced by the very limited connexion between the

understanding and the policy of men, to whom it is natural to err, even in designs the best conceived, both as to

their means and object; in addition to which, they are too frequently the result of prejudice or of ignorance.

Religion, which has always been the leading object of attention with civilized nations, is invariably connected with

their history; neither can the one fail in affording instruction as regards the other. If the history of a nation

deserves to be

26

destroyed and blotted out from the memory of man, merely because it is the record of superstition, idolatries, and

other errors, regugnant to true religion, then the sacred books, that are the foundation of our holy catholic faith,

would not have been exampted from the fatal misfortune which produced the destruction of the American Records.

The Hebrews, who were chosen by God, from among all nations, to be the depositories of his true religion and worship,

were not less inclined to idolatry, than were the American nations; for the sacred text informs us of their frequent

lapses from the divine ordinances, and of the various punishments inflicted by the Almighty for the purpose of

correcting and bringing them back to the path of truth, but it does not conceal from us the idolatrous errors into

which they were precipitated.

We no where read of, nor has it ever been asserted of the apostles, who with their inspired voices, desseminated

the mysteries of the catholic religion throughout the world, and who endevoured to esterminate idolatry, even by the

sacrifice of their lives, that they destroyed the histories of the Pagan nations in whose hearts they implanted the

true faith; even the holy fathers and doctors of the church neglect to have them compiled with the minute descriptions

of the many supertitious errors to which they were addicted.

The fate of the American histories immediately brought into action the pens of many learned men, natives as well as

27

Spaniards, and roused the attention of Phillip the second and of the first viceroys of Mexico, to replace, as far as

possible, so deplorable a loss (note 1). Their exertions do not prove if any essential service, as the histories which

they produced embrace only a few of the latter ages; neither do they appear to have employed much research in discovering

the origin of the Americans. At subsequent periods, however, many men of superior attainments undertook to write on

this subject (note 2). But what has proved the result? Notwithstanding all their zeal and application, after

undertaking much and having essayed through many different channels an investigation of how, and from whence the first

inhabitants of America came, yet, to the present period, no hypothesis has been advanced, that is sufficiently

probable, to satisfy a mind sincerely and cautiously desirious of arriving at the truth. This is the conclusion drawn

by that illustrious benedictine, Fray Benito Geronymo Feyjoo, in the twenty-fifth discourse of the fifth vol. of his

Teatro Critico, where he says: "After long study and attentive examination of so many, and such various opinions,

I find no one, having the necessary appearance of truth to satisfy a prudent judgment, and many that do not possess

even the merit of probability."

A research enveloped in so much obscurity, led the celebrated Guiseppo Antonio Constantini to declare, that whatsoever

may be advanced upon the subject, does not pass beyond the limit of mere opinion, as we have neither histories,

manuscripts, nor traditions of the Americans; the greater part of whom, he says, when they were discovered, were

ignorant

28

and uncultivated, and that the suppositions given by many writers are subject to inscrutable difficulties (note 3).

Francisco Xavier Clavigero, a modern American author, has said -- "that the history of the primitive population of

Anahuac is so obscure and so much involved in fable as to render it not merely a most difficult matter for solution,

but totally impossible to come at the truth" (note 4).

The darkness of this historical question opened the road to an attack upon the impregnable rock of religion. About the

middle of the last century, Isaac Peyrere erected his system of the Preadamites which he founded upon the more

philsophical than historical one, of the deluge, invented by Thomas Burnet in his sacred Theology of the Earth

(note 6) denying, on the one hand, the universality of the flood upon the earth, in opposition to the irrefragable

sense of the scriptures, and the uniform belief of the church, pretends, on the contrary with the synogogue, that all

the human race are not the descendants of Adam and Eve, and consequently denies original sin and the principle of our

holy catholic religion; producing the population of America as the chief support of this hypothesis, and the ignorance

that exists as to the source of its origin. Assuming the fact, that there is no communication between the two

continents by land, and not without traversing immense seas, he infers that, anterior to the invention of the mariner's

compass, men could not pass over either from Europe, Asia, or Africa; therefore, as it is clear that America was

peopled before the time of that invention, he infers therefore, that its inhabitants

29

are not the descendants, from those of the old continent; and therefore not indebted to Adam and Eve for their origin,

but to others of the human race both male and female, whom God had created at a much earlier period, and placed in

these southern regions.

Innovation is not to be tolerated in religion; for, being sole, holy and eternal, it is, as it has been, and as it will

be to the end of time, immutable; new doctrines may be admitted in philosophical matters, but even many of these become

dangerous and detrimental to religion from the influence which they may acquire. Thus, for instance, the systematic

novelties of Descartes and other modern philosophers, which, in the beginning, appeared to be neither morally good nor

positively bad, by time and the force of inference, went the length, not only of overturning the spirituality and the

immortality of the soul, and making it material and corruptible; but even proceeded so far as to destroy religion

itself so completely, as to fall into the still greater impiety of atheism: the system of Burnet gave rise to the

heretical one of the Preadamites; and there are many others of a similar stamp abounding in this inconsistent age of

ours, which advances such bold pretensions and calls itself the most enlightened.

Although the Almighty subjected nature to certain laws, he has, notwithstanding, reserved to himself a more supreme

dominion over her, and has, from time to time, been pleased to give the most resplendent demonstrations of his

omnipotent arm, in acts and incidents stupendous in themselves, and even

30

superior to those very laws. In such cases it is better to believe his works miraculous, than endeavor to make an

ostentatious display of our talents by the cunning invention of new systems, in attrubuting them to natural causes

(note 7). On this account, Burnet will always be reprehensible for the singularity of his system, as will many other

modern philosophers, for the notions they have disseminated; but, that of Peyrere, must ever be condemned for its

heretical principles: Feyjoo, father Garcia, and his illustrator, mentioned by Constantini, Clavigero, and all who have

written from the commencement of this century on the origin of the Americans, are alike open to the censure of being

careless investigators, in having passed over the indubitable memorials on the first inhabitants of America written

by the bishop of Chiapa, don Francisco Nunez de la Vega in his Diocesan Constitution, printed at Rome in 1702.

Among the many small historical works that fell into the hands of this illustrious prelate, who was not more zealous

for the glory of God, than he was mistaken in the interpretations he apploes to many of them, and particularly, when

he attributes the whole of them to superstition; instances one that was written by Votan, of whom he speaks as

follows in no. 34, section 30, of the preface to his Constitutions: "Votan is the third gentile placed in the calendar,

he wrote an historical tract in the Indian idiom, wherein he mentions, by name, the people with whom, and places where,

he had been; up to the present time theree has existed a family of Votans in Teopizca. He says also that he is lord of

the Tapanahuasec (note 8);

31

that he saw the great house (meaning the tower of Babel), which was built by the order of his grand-father Noe (Noah),

from the earth to the sky; that he is the first man whom God sent hither to divide and portion out these Indian lands;

and that, at the place where he saw the great house, a different lanhuage was given to each nation."

This illustrious prelate could have communicated a much greater portion of information relative to Votan and to many

other of the primitive inhabitants, whose historical works, he assures us, were in his own possession; but feeling some

scruples, on account of the mischievous use the Indians made of their histories in the superstition of nagualism

(note 9), he thought it proper to withhold it for the reasons assigned in no. 36, section 32 of his preface.

"Although," says he, "in these tracts and papers there are many other things touching primitive paganism, they are not

mentioned in this epitome, least, by being brought into notice, they should be the means of confirming more strongly

an idolatrous superstition. I have made this digression, that it may be observed in the Notices of the Indians (the word

idols is here used which seems to be an error of the press), and the substance of the primitive errors, in which they

were instructed by their ancestors."

It is to be regretted that the place is unknown where these precious documents of history were deposited; but still

more is it to be lamanted, that the great treasure should have been destroyed: this treasure, according to the

Indian tradition, was

32

placed by Votan himself, as a proof of his origin and a memorial for future ages, in the casa lobrega, (house

of darkness) that he had built in a breath, that is, in the space of a few breathings, a metaphorical expression

intended to imply the very short space of time employed in its construction. He committed this deposit to a

distinguished female, and a certain number of plebian Indians appointed annually for the purpose of its safe custody.

His mandate was scrupulously observed for many ages by the people of Tacoaloya, in the province of Soconusco, where it

was guarded with extraordinary care, until being discovered by the prelate before mentioned, he obtained and destroyed

it. Let me give his own words from no. 34, section 30 of his preface -- "This treasure consisted of some large earthen

vases of one piece, and closed with covers of the same material, on which were represented in stone, the figures of

the ancient Indian pagans, whose names are in the calendar, with some calchihuites, which are solid hard

stones, of a green colour and other superstitious figures. -- These were taken from a cave by the Indian lady herself,

and the Tapienes or guardian of them, and given up; when they were publicly burnt in the square at Hueguetan, on our

visits to that province in 1691."

It is possible that Votan's historical tract alluded to by Nunez de la Vega, or another similar to it, may be the one

which is now in the possession of Don Ramon de Ordonez y Aguiar, a native of Ciudad Real; he is a man of extraordinary

genius, and engaged at this time, in composing a work, the title

33

of which I have seen being as follows, Historia del Cielo y de la Tierra; that will not only embrace the

original population of America, but trace its progress from Chaldea immediately after the confusion of tongues; its

mystical and moral theology, its mythology and most important events. His literary acquirements, his application to,

and study of the subject, for more than thirty years, his skill in the Tzendal language, in which idiom the tract

just spoken of is written, and the many excellent authors he has collected, lead us to anticipate a work, so perfect

in its kind, as will completely astonish the world.

To the important information of Nunez de la Vega, I will add the no less valuable notices communicated to me by

Don Ramon Ordonez y Aguiar. The memoir in his possession consists of five or six folios of common quarto paper,

written in ordinary characters in the Tzendal language, an evident proof of its having been copied from the original

in hieroglyphics, shortly after the conquest.

At the top of the first leaf, the two continents are painted in different colours, in two small squares, placed

parallel to each other in the angles: the one representing Europe, Asia, and Africa, is marked with two large SS;

upon the upper arms of two bars drawn from the opposite angles of each square, forming the point of union in the

centre; that which indicates America has two SS placed horizontally on the bars, but I am not certain whether upon

the upper or lower bars, but I believe upon the latter. When speaking of the places he had visited on the old

continent, he marks them on the margin of each

34

chapter, with an upright S, and those of America with a horizontal S. Between these squares stand the title of his

history. "Proof that I am Culebra" (a snake), which title he proves in the body of his work, by saying that he is

Culebra, because he is Chivim. He states that he conducted seven families from Valum Votan to this continent and

assigned lands to them; that he is the third of the Votans; that, having determined to travel until he arrived at

the root of heaven, in order to discover his relations the Culebras, and make himself known to them, he made four

voyages to Chivim (which is expressed by repeating four times from Valum Votan to Valum Chivim, from Valum Chivim

to Valum Votan); that he arrived in Spain, and that he went to Rome; that he saw the great house of God building;

that he went by the road which his brethren the Culebras had bored; that he marked it, and that he passed by the

houses of the thirteen Culebras.

He relates, that, in returning from one of his voyages, he found seven other families of the Tzequil nation, who

had joined the first inhabitants, and recognized in them the same origin as his own, that is, of the Culebras. He

speaks of the place where they built their first town, which, from its founders, received the name of Tzequil; he

affirms the having taught them refinement of manners in the use of the table, table cloth, dishes, basins, cups and

napkins; that, in return for these, they taught him the knowledge of God and of his worship; his first ideas of a

king and obedience to him; and that he was chosen captain of all these united families.

35

It would be of great importance to have this memoir literally translated; for although it is written in a laconic

and figurative style, it would lead to a more ample interpretation and illustration of history, both divine and

human; indeed, such a translation may be considered requisite to the gratification of the public, and, on another

account, because a great number of persons are likely to produce more accurate observations and discoveries than

an indivudual is able to achieve; but, as the proprietor of this fragment espreessed himself to me, we must be

satisfied, for the present, with the little that has been accomplished, (considering the difficulty of understanding

the sentences and situations of the p;aces mentioned), towards construing it, insufficient as it is, to clear up

the historical obscurity which has hitherto fatigued the greatest talents of the world to no good purpose.

Let us now follow the progress of this celebrated chief of the first inhabitants of the American continent, let us

examine his narrative carefully, and observe if it agrees with the histories and antient traditions of the writers

of both hemispheres, and compare it with some of the few monuments and documents furnished by Antonio del Rio, captain

of artillery, who was sent in consequence of an order from his Majesty Charles the third, dated March 15th 1786, by

his Excellency don Joseph Estacheria, captain general of Gautemala, to examine the ruins of a city of very great

extent and antiquity, the name of which is unknown, that was discovered in the vicinity of Palenque, district of

Carmen, in the province of Chiapa where he found

36

magnificent edifaces, temples, towers, aqueducts, statues, hieroglyphics and unknown characters, that have withstood

the raveges of time and a succession of ages, and of which he made many plans and drawings.

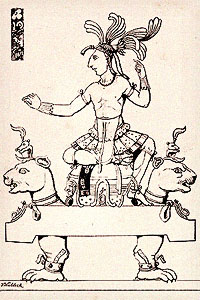

Among the figures which this officer copied, are two that represent Votan on both continents, and an historical event,

the memory of which he was desirous of transmitting to future ages.

The first figure displays Votan adorned with many hieroglyphics, the meaning of some of them I will explain, unless my

humble abilities mislead me. -- The hero has a symbolical figure twined round his right arm; this is significative of

his voyages to the old continent. The square, with a bird painted in the centre, indicates Valum Votan: whence he

commenced his travels; and it is an Island, because among antiquarians it is unanimously agreed, that a bird is the

symbol of navigation; for only by the means of navigation could his voyages be undertaken; the remainder of the figure

shews the course taken to reach Valum Chivim.

The figure, with the bird in the middle, resembles the one I stated as descriptive of his maritime route to the other

old continent; but the bird being figured in an opposite direction, denotes his return to Valum Votan. He holds in his

left hand a sceptre, from the top of which issues the symbol of the wind, such as Clavigero in his second vol. states

it to have been represented by the Americans. Dependant from the right hand is a double band, but to avoid repetition,

I shall reserve the meaning of this until I explain the second figure, as well as that of the

37

deity at his feet, in the act of supplicating to be taken to America, in order to be there known and adored.

The second figure shews Votan returned to America; the deity, before seen kneeling at his feet, is here placed on a

seat covered with hieroglyphics; Votan, with his right hand, is presenting him a sceptre armed with a knife of the

ytzli stone, known here under the name of chay: it is a species of black quartz, but it is sometimes

found of other colours, it is vitreous, semi diaphanous and infusible; the natives armed with their lances and

arrows with this instead of iron which was unknown to them, they frequently formed swords of the same by placing

it in a piece of wood split lengthways; and also used it to make knives employed in their sanguinary sacrifices: by

this act Votan shews the deity to be a principal one to whom sacrifices were offered. Votan has in his turban the

emblem of the air, and a bird with its beak in an opposite direction to his face, to signify his sailing from that

side of the world to this. From his left hand hang the two bands spoken of in the first figure, but they are here

more distinct than in that; the lower band shews the line of his descent on the old continent, and the upper one

exhibits his American progenitors. The three human hearts shew, that he who holds the band, is Votan, and the third

of his race, as he represents himself to be in his historical account. To comprehend this more clearly, it must be

observed, that the word Votan in Tzendal language, means heart; Nunez de la Vega, speaking of this hero of

antiquity in no. 34, section 30, says: "This Votan is much venerated by all the Indians, and in one province they

look upon him as the heart of the people.

38

By comparing Votan's narrative on the subject of his voyages to, and returns from, the old continent, and of his

being the third of the race; with the duplicate effiges of him which Captain del Rio found sculptured on stones, in

one of the temples at the unknown city, that we will, for the present, designate as the Palencian; we shall have a

very conclusive proof of its truth, and this one will be corroborated by so many others, that we shall be forced to

acknowledge this history of the origin of the Americans, excels those of the Greeks, the Romans, and the most

celebrated nations of the world, and even worthy of being compared with that of the Hebrews themselves.

If we accompany this renowned hero and writer of antiquity, I do not hesitate to assert, that he will leave us fully

satisfied with his veracity on the important point of the American population, and whence it proceeded; thereby putting

an end to the conjectural assumptions of modern authors, by enforcing a belief of testimonies so ancient and venerable,

and confirming a discovery made in our own times, which will cause the despised authorities of the ancients to be

received, and smooth those difficulties, hitherto produced by the readiness of writers, to escape from the real

obscurity of the subject, by starting [sic - stating?] brilliant ideas instead of seriously discussing facts.

Before we proceed, it is necessary to identify the deity who has been already described in one place, in the act of

supplication, and in another, as seated on the throne of the altar, and receiving the symbol of homage and adoration

from that hand whence he had before implored favour.

The mitre or cap, with the bull's horns, which this idol

39

bears on its head in both figures, removes all soubts as to his being the celebrated Osiris of the Egyptians, who,

according to Diodorus Siculus, is the same as Mesraim or Menes, son of Cham and heir to the kingdom of Egypt, known

to the Greeks and Romans, and worshipped by them as Dionysius or Bacchus; adopted also by other nations under different

names, and particularly by the Phoenicians, all firmly believing in him, and that, in every place and under what name

soever he was the active power of nature, viz: the good spirit, good fortune, and the bestower of all virtue,

prosperity and joy. On the other hand, his enemy Typhon was believed to be the evil principle, the general cause of

misfortunes and vices; whom, according to Plutarch, neither order nor reason, affections nor family, light nor health

could restrain; for this cause whatever preturbed or disfigured nature, even to the very eclipses, was attributed to

him.

The great aptness of Osiris in the invention of the arts necessary to social life; his justice in settling disputes

between individuals, his prudence in transmitting to his children the inheritance that had descended to him from his

father; finally, his strength and courage in destroying ferocious beasts, obtained for him the confidence and love of

his subjects, or rather, of his family, as it is probable that all the Egyptians were either his brothers or nephews,

over whom he had no other right than that which was conferred by primogenitureship. This people has always continued

firm in the belief of being indebted to him for the art of cultivating the ground, of grinding corn, of making and

40

baking bread, of cultivating the vine, flax, hemp, and the aromatic peculiar to Egypt, and of preparing the wool of

animals, for the clothing of men.

The gratitude due to him for discoveries so numerous and so useful, was accompanied by the effections of his people;

but, not content with making them happy, he sought to extend his humanity to the most remote nations, who, living

like the beasts of the forest, were unacquainted with the benefits of social life.

With this information, he left the government of his kingdom in charge of his equally humane and virtuous sister and

wife Isis, and attended by a large army,in which there were a great number of musicians and dancers of both sexes, he

departed; not with the intention of conquering kingdoms, but impelled by the desire of subduing the hearts of men,

by instructing them in the same arts, he had taught his own subjects, thinking, most reasonably, that it would be

more glorious to succeed by persuasive means in drawing mankind from the rude and wandering mode of life they had

hitherto led, than by force, to attempt bringing them to that gentleness of manners, consistent with the true

character of humanity.

His indefatigable zeal and incessant love towards the human race, his heroic object of rendering them happy without

a thought of depriving them of their liberty, begat a veneration so profound, that it quickly proceeded to the excess

of paying divine honours to a man who only sought to imitate the author of nature in his natural goodness.

A reign so fraught with general felicity well deserved to be

41

eternized; but it was shortened by an enemy rendered more terrible and dangerous, because unsuspected, and allied by

the closest ties of consanguinity. This enemy was Typhon, his own brother, a wretch excited by the fierce spirit of

envy, who contrived schemes to obscure the fame of him he could not imitate; and, being assisted by his compeers, he

conspired against his brother's life, and repeated the atrocious crime of Cain. In the absence of Mesraim, Typhon

secretly formed a party, and, accompanied by twenty six traitors, assassinated him on his return. -- Villainy so

atrocious, could not be long concealed by the shallow contrivance of spreading a report, that the king had been

devoured by a crocodile or hypopotamus. -- It was soon ascertained that his body had been cut into as many pieces as

there were conspirators; Typhon supposed that, dividing the body of Menes among his accomplices, would inflame them

against the memory of the prince, and, as he was ambitious as well as cruel, he expected to be able to engage them,

as a consequence of their barbarity, in support of his usurpation of the crown.

Impious and inhuman Typhon, may thy memory be accursed with interminable hatred, for daring to stain thy murderous

hands, with the blood of thy brother and thy king, thus leaving to posterity the execrable example, of a two fold

crime so horrible; thy ambition caused a polished people to tear asunder the most sacred bonds, to precipitate

themselves into the greatest atrocities, to tarnish the glory of their ancestors, and to disgrace their nation!

As soon as Isis was informed of Typhon's barbarity, inflamed

42

with rage, and assisted by her eldest son Orus, known to the Greeks by the name of Apollo, she avenged the death of

her husband. With a powerful army of her faithful subjects, who, no less incensed than herself at the melancholy fate

of their beloved monarch, and equally eager to take vengeance; she went in pursuit of the murderer, fought a sanguinary

battle, defeated, took him prisoner, and then put him to death with the most guilty of his rebellious partizans.

Not satisfied by this punishing the infamous brotherm Isis resolved to gives proofs of piety and affection for her

husband, and collected the dispersed portions of his mutilated body, to honour them with obsequies of so good a king.

Only one part of the corpse was deficient, and this had been thrown into the Nile, because none of the conspirators

would carry it away. -- Isis greatly lamented this lost portion, and therefore resolved that more respect and

veneration should be paid to it than to nay other: for this purpose she pretended to have found it, and, to celebrate

the recovery, ordered that all the women should carry its effigy suspended from their necks (note 10). This effigy,

deemed impure by us in modern times, was greatly honored by the antients, and, by some nations, even now continues

to be venerated. The Bramins of India carry it in solemn procession at certain festivals, and present it to be kissed

by the people, who believe that they are paying devotion to the author of nature, by honoring the symbol of fecundity,

which they Greeks named Phallo, and the festivals in honor of the same, Phallophorides, see Descartes at

these words.

As Osiris had taught men the art of tillage, the priests

43

chose the ox, as a symbol of agriculture, to represent this defied prince; the cow was chosen as the type of Isis who

was raised to a divinity after her death; and this symbolized ox and cow they called Apis. Hence it is that Osiris

was represented with a mitre from which issue two horns, as spoken of in the figures just described. Sometimes a

twisted or crooked stick was placed in his left hand, and a sort of strap or thong with three ends in his right, this

strap may be observed below the knees of the first figure, and with the distinction of the three ends in the right

hand of the second.

Diodorus Siculus, lib. 1, has left us a description of Osiris found upon ancient monuments, which shews what the

people, who adopted his worship, thought of him -- viz. "Saturn, the youngest of all the gods, was my father; I am

the king Osiris, who, followed by a powerful army, overran all the earth, from the arid sands of India to the

frosts of the bear; and, from the source of the Ister, to the shores of the ocean, so that my inventions and my

benefits were carried into every region."

The superstition of the antients was not satisfied by perpetuating the fame of Isis and Osiris, but it was also

necessary to conciliate the infamous Typhon, known in fabulous history under the name of Python, which is only an

inversion of the same letters; to the former they offered sacrifices to obtain favors, as they did to the latter to

escape injuries.

In the present day Osiris is recognized by the people of Upper Tartary and in China as the god of heaven, and the

dispenser of good; and Typhon as the god of the earth and inflictor

44

of evils; he is worshipped under the form of an idol cloathed with skins and called Natogai. The belief in beneficent

and malignant deities was common with the Americans during their idolatry. In Typhon they even now fear the devil; but

he does not, at present, possess the power of seizing those who speak ill of him. In my mythological fable, that is

chiefly founded upon the events of Egyptian history, the victory of Apollo over Typhon is well known: it is feigned

that the latter, overwhelmed by shame and rage, fled from his conqueror; and wandering through the deserts, under the

form of a serpent, was at last destroyed by a thunderbolt.

The Egyptians conceived so much animosity and aversion to the domestic enemy of their country, that, because Typhon

had red hair, they could not suffer any one whose head was distinguished by that obnoxious colour to remain alive. An

unfortunate stranger, with the proscribed chevelure, happening to arrive in the country shortly after the death

of Osiris, encountered the fury of the people, who dragged him to the sepulchre of the king and immediately immolated

him to his manes.

The following is a drawing from the figure which Captain del Rio found in the temple before mentioned, and describing

this event as do several other figures of Bacchantes sculptured on the walls, which are detailed in his report. It

reoresents a priest performing the initiatory purification of the victim, who is placed on the tomb of Orisis, which

is decorated with many Phalli connected. In this temple, the same gentleman discovered the figure of Isis which

accompanies his memior. It has on its head

45

a cap similar to that of Osiris, and holds with both hands a twisted stick adorned with flowers, having at one end,

a human head, the symbol of royal authority in the administration of justice, and of the duties of sovereigns, both

political and civil, in providing for the happiness of the subject, by giving encouragement and promoting religion,

arts and sciences in their dominions. The male figure, with a sceptre in his hand, is Mercury, whom Osiris left as

chief counsellor and minister to Isis during his absence. This Mercury was the celebrated Athotis or Copt of the

Egyptians, second son of Isis and Osiris; a prince of extraordinary prudence and ability, known among the Greeks as

Thot or Thaut, Theutat by the ancient Celts, and Mercury by the Latins. He founded the city and kingdom of Thebes

in that part of Egypt which fell to his share on the monarchy being divided between his brothers and himself, after

the death of their father. Mercury was the inventor or restorer of the art of writing by sacred hieroglyphics, the

knowledge of which was confined to the priesthood alone, under pain of capital punishment in the case of revealing

the same; he also invented the common method, in a different character, for the use of the people. Didorus Siculus,

on the book before cited, has preserved the valuable inscription of Osiris, mentioned by him, and another of Isis

in the following terms: "I am Isis, queen of this country, I had Mercury as my chief minister: no one was able to

resist the execution of my commands. I am the eldest daughter of Saturn, the youngest of all the gods, sister and

wife of Osiris, the king, and mother of king Orus."

The abbate de Castres, in the fourth vol. of his Mythological

46

Dictionary of Pagan Ages, speaks of a large copper plate called the Isiac table, found at Rome, in 1525, on which

were engraved many Egyptian gods, and in particular many figures of Isis with various symbols. It was purchased by

cardinal Bembo, and afterwards passed into the duke of Mantua's possession, after whose death it was splendidly

engraved in its full size, by Eneas Vico of Parma. The plate is divided into three horizontal bands which are

occupied by Egyptian deities and a great number of hieroglyphics that Pignorio, in his Mesa Isiaca, and father

Kircher, in his Oedipus Aegeyptiacus, have explained, and, I doubt not, but their expositions may serve to interpret

the Egyptian figures and deities of the Palencian city and more particularly the hieroglyphics.

Although the figure of Votan is not found among these, yet, having the fabulous history of Isis and Osiris fully

delineated, (without adverting to many other ultramarine subjects found by del Rio, that will, of themselves, afford

matter for many conclusive proofs), there is a very powerful argument to remove doubts about the existence of a

maritime communication between the two continents in the very remotest ages of antiquity; but, finding the duplicate

figures of Votan in the attitudes we have described, and combining the Indian tradition, that Nunez de la Vega

found verified by his discovery at the casa lobrega, with the small portion of information this illustrious prelate

has communicated, and with the little added thereto by the presbyter Ordonez, these are conclusive proofs in favor

of Votan; the truth of his voyages to the old continent, and of his being the first populator of the new world.

47

I repeat, let us confidently follow this ingenious historian, and examine what he means by Culebra, and what proofs

he gives of being Culebra. His words are, "I am Culebra, because I am Chivim:" this, at first sight, appears a very

short and inconclusive argument, but with a little study, admits of a clear and convincing explanation.

Among the few writers I have consulted, in order to comprehend Votan, the benedictine Calmet, in his Commentaries

on the Old Testament, has cleared the way for me, and saved much trouble in this work, as, by diligent study and

unwearied industry, he has collected whatever the most esteemed ancient authors have produced, in my opinion

as most probable.

Let us suppose then, with Calmet and other authors whom he quotes, that some of the Hivites, who were

descendants from Heth, son of Canaan, were settled on the shores of the Mediterranean sea, and known

from the most remote periods under the name of Hivim or Givim, from which region they were expelled,

some years before the departure of the Hebrews from Egypt, by the Caphtorims or Philistines, who,

according to some writers, were colonists from Cappadocia, others conceiving them to be from Cyprus,

and, more probably, according to a third opinion from Crete, now Candia; that, to strengthen their native

country Egypt, and to protect themselves from all assault, they built five strong cities, viz. Accaron,

Azotus, [Ashdod], Ascalon and Gaza, from whence they made frequent sallies upon the Canaanite towns and all

their surrounding neighbours, (except the Egyptians, whom they always respected,) and carried on many wars

in the posterior ages against the Hebrews (note 11).

48

The scriptures, Deuteronomy chap. 2, verse 23, and Joshua, chap. 13, verse 4 inform us of the expulsion

of the Hivites, (Givim) by the Caphtorims, from which it appears that the latter, drove out the former,

who inhabited the countries from Azzah to Gaza. Many others were settled in the vicinity of the mountains

of Eval and Azzah, among whom were reckoned the Sichemites and the Gabaonites; the latter, by stratagem,

made alliance with Joshua, or submitted to him; lastly, others had their dwellings about the skirts of mount

Hermon beyond Jordan, and to the eastward of Canaan. Joshua, chap. 11, 3. Of these last were Cadmus and his

wife Hermione or Hermonia, both memorable in sacred as well as profane history, as their exploits occasioned

their being exalted to the rank of deities, while in regard to their metamorphosis into snakes, (culebras)

mentioned by Ovid, Metam. lib. 3, their being Hivites may have given rise to this fabulous transmutation,

the name in the Phoenician language implying a snake, which the ancient Hebrew writers suppose to have been

given from this people being accustomed to live in caves under ground like snakes (note 12).

Cadmus, in the opinion of Suidas, was the son of Agenor or Ogyges, who, according to Calmet, is the giant

Og, king of Basan, (situated at the foot of mount Hermon) who was vanquished and slain with all his family

and followers by Moses when he entered into the land of promise, about the year of the world 2253, which

agrees with 1451 of the vulgar era, and 1447 before Christ. -- We are told of his immense stature in

Deuteronomy, 3, 11, by the enormous size of his iron bedstead, the length of which is described in cubits,

viz. 9 by 4. In the time of Moses,

49

sojourning in the wilderness. Cadmus accompanied by his sister Cilix, his mother Telephassa and a numerous

company of his friends who were desirous of sharing his fortunes, quitted his father at the entreaty of

his sister Europa, to take revenge upon Jupiter, who had transformed himself into a white bull and carried

her away: some mythologists, however, suppose that the ship in which she was transported had the figure of

a white bull at its prow, and in this manner the fable originated; but the most probable conjecture is,

that he abandoned his country from a reasonable dread of the sentence promulgated by the Almighty for the

total destruction of the children of Canaan, of which the Hebrew people was destined to be the instrument;

and this fear might have been increased by the dreadful plague of hornets that preceded the Hebrew invasion

(note 13).

The first enterprise undertaken by Cadmus was the conquest of the Sidonians, (the descendants of Sidonius,

eldest son of Canaan,) and the foundation of the kingdom of Tyre in that part of the country, bounded on the

west by the Mediterranean sea, and by the Red Sea on the east; a situation most convenient for extending the

great commerce that has rendered this people so celebrated in history, both sacred and profane. The

establishment of this kingdom is fixed by Calmet, anno mundi 2549, or 1455 before Christ, and which year,

he says, corresponds with the 37th of the Israelites wandering in the wilderness: about the same period

Cilix founded the kingdom of Cilicia, on the confines of Tyre, and on the same coast of the Mediterranean.

Cadmus was not satisfied with this conquest, but recollecting

50

the success of Cecrops, an Egyptian prince, who, eight years before, had subjugated that part of Greece

where he founded the kingdom of Athens, and considering Greece, well peopled as it was, an object worthy

of his ambition, and the conquest of it within his power, he directed his views toward Boeotia; not at

all intimidated by the circumstance of its being then governed by the valiant Draco, a son or a descendant

of Mars. "The commencement of this enterprise was commensurate with his wishes; his progress was brilliant;

but the termination disastrous; as it happens in small monarchies when the chiefs, prompted by ambition

and covetousness, mutually seek each other's destruction, and finally become the victims of the most

powerful." Calmet, lib. 1, cap. 8.

Cadmus founded the city of Thebes. situated near mount Parnassus, the capital of his empire, and fortified it

with a citadel' which he called Cadmea' after his own name.

The epoch of the foundation of Thebes is ascertained from one of the Parian marbles, (now called the Arundel

marbles, because the earl of Arundel, an English nobleman, at a very great expense, transported them to his

own country) to have been in the sixty-fourth year of the Attican era, indubitably coinciding with 3195 of

the Julian, and 1519 before the Christian era; at which period, Moses was with his father-in-law Jethro,

in the land of Midian (note 14).

Greece was indebted to Cadmus for the art of writing, the cultivation of the vine, the consecration of

images, the rights of sanctuary so scrupulously respected by antiquity, and the use of

51

arms offensive and defensive; he was the first warrior who armed his soldiers with helmets of copper, and he taught

the extraction of this metal from the mineral containing it, and which, up to the present day, has retained the

name of Cadmia. His disastrous end did not prevent the superstition of the times from celebrating his worth,

his talents, and his valour, by placing him among the demi-gods. The fable says, that his soldiers, having

been killed by a serpent near a fountain, whither they went to fetch water, (alluding to a battle that he

lost against Draco,) he avenged their death by killing their destroyer, from which he pulled out the teeth,

and sowing them, by the advice of Minerva, they produced a plentiful harvest of armed men, so warlike, and

so fiery in their tempers, that, upon a slight disagreement arising between them, they fought and killed

each other, excepting five only, by whom this part of Greece was afterwards peopled. This is not a proper

place to discuss the meaning of the fable: unseasonable erudition seldom fails to weary the reader, and

leads his attention from the principal subject under consideration; Homer and many other grave authors have

transgressed by such a display; it is, nevertheless, undeniable, that this fable is one of the greatest

supporters of history; I cannot, however, forbear remarking, that the Phoenician words expressive of a copper

helmet were so ambiguous as to signify also a man armed for war, a serpent's teeth, and the number five.

The invention of such a fable, its being fostered and propagated, either by the priests of the deified

personage, or the princes, his descendants and successors, might have occasioned

52

the first and true meaning of the words to be forgotten; while their own interest or convenience may have

engrafted the deception on the minds of the vulgar, who, from ignorance and simplicity, are always prone to

credit portentous novelties, more particularly, when they tend to identify the characters of their beloved

princes with their national glory; and especially when their religion is concerned.

It is also necessary to observe, that the names of Cadmus and Hermione are not proper to these persons:

Hermione was so called from being born a Hivite among those who dwelt near mount Hermon: while Cadmus

signifies an eastern man, or one who comes from the country situated towards the east; but this denomination

was not indiscriminately given to all Orientals, as Calmet together with other authors quoted by him,

believes; but it properly belonged to the Hivites near mount Hermon, who were known as Kadmonites or

Cedmonites, from the Hebrew word kedem, which, according to the interpretation of the rabbi Jonathan,

Genesis, chap. 15, verse 19, means east; and Calmet also places them in this situation. Paraphrastres of

Jerusalem, in glossing the word Heveum, chap. 10, verse 17, of Genesis, is, in my opinion, more correct

in rendering it Tripolitanum, meaning to insinuate, as Calmet says, that "the Hebrews removed themselves

to Africa, into the kingdom of Tripoli," or to speak more accurately, to Tripoli of Syria, a town in the

kingdom of Tyre, which was anciently called Chivim. Under this supposition, when Votan says he is Culebra,

because he is Chivim, he clearly shews, that he is a Hivite originally of Tripoli in Syria

53

which he calls Valum Chivim, where he landed in his voyages to the old continent.

Here then we have his assertion, I am Culebra, because I am Chivim, proved true, by a demonstration as

evident, as if he had said, I am a Hivite, native of Tripoli in Syria, which is Valum Chivim, the port

of my voyages to the old continent, and belonging to a nation famous for having produced such a hero as

Cadmus, who, by his valour and exploits was worthy of being changed into a Culebra, (snake,) and placed

among the gods; whose worship, for the glory of my nation and race I teach to the seven families of the

Tezquiles, that I found, on returning from one of my voyages, united to the seven families, inhabitants

of the American continent, whom I conducted from Valum Votan, and distributed lands among them.

Should a scrupulous reader not feel conviction from this interpretation, the brass medal, of which two

specimens were found, one of them now in the possession of Don Ramon Ordonez, the other, which was my own,

I presented to the King, with two copies of this work by the hands of the President, on the 2d of

June, 1794, will remove every doubt on this head, (the drawing is in all respects the same as the original,

except being rather enlarged,) and fully authenticate the rest of what Votan relates in his history, as

well as demonstrate that the American tradition as to his origin and his expulsion from the kingdom of

Amaguemecan, which was his first disaster on this continent, applies to him; while the narrative and the

medal, assisted by some portions of information from

54

Captain del Rio, will elucidate a few historical fragments which have been related by writers of the greatest

authority, but are considered apocryphal by the most esteemed modern authors.

The medal is a concise history of the primitive population of this part of North America, and of the

expulsion of the Chichemecas from Amaguemecan the capital of which indubitably was the Palencian city,

hitherto sought for in vain, either to the northward of Mexico, or in the north of Asia. This history,

comprised in so small a compass, is the best panegyric that can be given upon the sublime genius of its

inventors, of whose descendants, at the time of the conquest, it was a matter of doubt whether they possessed

rationality or not. -- On one side, the first seven families to whom Votan distributed lands are symbolized by

seven trees; one of them is withered, manifestly indicating the extinction of the family it represented;

at its root, there is a shrub of a different species, demonstrative of a new family supplying its place. --

The largest tree is a cieba, wild cotton, placed in the midst of the others, and overshadowing them

with its branches; it has a snake, Culebra, twined round its trunk, shewing the Hivite, the origin of all

these seven families; and the principal posterity of Cadmus in one of them; it also exposes the mistake of

Nunez de la Vega, in applying the symbol of the cieba to Ninus (note 17), and more strongly than ever

establishes the derivation of Votan and the seven families he conducted hither from the Culebras. The

signification of the withered tree, the shrub at its foot, and the bird on

55

the top, I shall give when I speak of the idol Huitzlopochtli. -- The reverse of the medal shews other seven trees,

with an Indian kneeling, the hands joined, the countenance sorrowful, the eyes cast down, in the act of invoking

divine help in the serious tribulation that afflicts him: this distress is typified by a crocodile on each side,

with open mouth, as if intent on devouring him. -- These devices doubtless imply the seven families of the Tzequiles,

whom Votan says he found on his return from Valum Chivim. -- Although it may not be an easy matter to assign

a reason why each tree is expressive of each family in particular, it is incontrovertible, that the Mexican

nation had the Opuntia or Nopal, (two of them), as its peculiar device therefore, the others might, in the

same manner, have belonged to other tribes now unknown. An eagle, with a snake in its beak and claws, on

the Nopal is also confirmatory of Votan's having recognised in the Tzequiles the same origin from the

Culebras as his own; and strengthens the Mexican tradition, of his having been driven from Amaguemecan.

Clavigero, in his ancient history of Mexico, vol. I, book 2, speaks of this kingdom, and the arrival of

the Chichemecas at the city before mentioned, which he calls the country of Anahuac and interprets the

name to mean "the place of the waters:" he says their native country and principal city was named

Amaguemecan, a word implying the same meaning as Anahuac, where, according to their own account, many

kings of their nation had reigned. Torquemada says, he found, from the Mexican written and oral histories,

that there had existed three kings of Amaguemecan.

56

The traditions alluded to by Torquemada receive some confirmation from Captain del Rio's Report, in which

he says he found in the corridor of a building, (called by him the great house, casa grande, in the

Palencian city), three crowned human heads, cut in stone; and connected with the same, by a line proceeding

from the hinder part, there were figures representing different subjects. -- In this manner, the antients

used to describe their sovereigns; and, in still more remote periods, their deities. -- It is known beyond

the possibility of doubt, that, in the early ages of paganism, the idols were represented by symbols or

symbolical figures only; until, in the course of time, painting and the sculpture of human figures were

introduced, and afterwards greatly improved by Daedalus of Crete. -- Thus, formerly, a trident was the

synonymy of Neptune, until the improved art of designation placed a human head before it; a shield or a

club indicated Hercules; a sword or a shield, Mars; so that each deity or demi-god was known by his

appropriate symbol.

The Mexicans followed this method to express the names of their kings, and transmit the remembrance of

them to posterity, and, in so doing, they used the same means of description that they had been taught

by their ancestors from the old continent. Clavigero has given, in his second volume, portraits of the

nine monarchs who occupied the Mexican throne. The first was Acamapitzin, represented by a crowned head,

to the posterior part of which, joined by a line, is the device of a hand grasping some reeds, because

the name Acamapitzin signifies "one who has reeds in his hand." -- The second was Huitzilihuith, who had

for his device the small bird called chupaflores, or chupamiel

57

(the humming bird), with one of its feathers in its beak; Huitzilihuith meaning a chupaflore's feather.

The third, Chimalpopoca, had a shield emitting smoke; his name by interpretation, is "a smoking shield." The

fourth, Itzcoate, a snake armed with small lances, the itzli stone; the name implying "snake armed with itzli," --

and in like manner for the others.

Another important monument, still more clearly elucidating the Mexican tradition and Torquemada's story of the

kings of Amaguemecan, is the tower discovered by del Rio in the court-yard of the great temple: it consists of

three stories or floors, which was beyond a doubt the sepulchre of the three kings. He found the entrances to

the tower stopped up, and having ordered some of them to be opened, was surprised to see the interior filled

with loose sandy earth, but knew not from what cause, being unacquainted with the practices of the Americans;

and he was still more surprised on finding an interior wall connected with that of the exterior. The supposition

to be drawn from such a circumstance, is, that for the purpose of raising the third story, for the sepulchre of

the last king, the directors of the work, found it necessary to give a more extended circuit to the building,

and therefore devised the expedient of strengthening it by an outward wall, and perhaps with the intention of

continuing other stories as cemeteries for future kings, until the whole should have attained a very considerable

altitude.

In the small turrets on the top of the tower, Rio found two stones imbedded in the walls: on these were sculptured

two female figures with extended arms, each supporting an infant;

58

this circumstance appears to point out the burial places of two queens, or two young princesses, or perhaps of

both. Of these figures he took drawings, but they are imperfect, as the faces had disappeared beneath the mouldering

touch of time.

Combining then the tradition of the Mexicans, as related by all writers on their history, respecting their kingdom

of Amaguemecan, of there having been three Chichemecan kings; of their expulsion from thence, as mentioned by

Torquemada and confirmed by del Rio's account of the three crowned heads, accompanied by devices similar to those

used by the Mexicans to represent their sovereigns; the tower divided into three portions, in each of which was

deposited the body of a king: keeping also under consideration Votan's history, and that, so ingeniously shown by

the medal; all these circumstances united tend to demonstrate, by evidence as clear as evidence can prove, that

the kingdom of Amaguemecan was situated in the present province of Chiapa; and that all the writers, who have

embraced the opinion that it existed in the north of America, or in Asia, have continued in error. -- They may have

been misled by discovering in some accounts, that the Chichemecas and other tribes came from the northward to

possess themselves of the kingdom of the Tultecas, which had been nearly depopulated by the plague; they appear

however to have overlooked the information they might have acquired, or perhaps did acquire, that the earliest

inhabitants of America came from the eastward; that they proceeded from the eastern part to the northward, and

again descended thence; or, more probably, from carelessness of research than from

59

a total want of information, which, how slender soever it might have been, their curiosity should have prompted them

to examine thoroughly.

Of this historical fact, Herman Cortes obtained intelligence from the Emperor Moetezuma himself, almost immediately

after his arrival: the information was confirmed in a most solemn manner when Moetezuma and the nobles of his

empire assembled to swear homage to the monarch of Spain, Charles V; Cortes however supposing Moetezuma was mistaken,

paid no attention to his account: he was himself deceived, and continuing in this belief, has been the cause of

succeeding writers perpetuating the error, if I may be permitted to speak so decisively. -- In order however to

fix the reader's attention to what I have here asserted, I shall introduce, literally, the two discourses of

Moetezuma, as Cortes communicated them to his Majesty Charles V, in his first letter, dated October 30, 1520. --

This, with several other letters, notes and documents, was reprinted at Mexico in 1770, by order of Don Francisco

Antonio Lorenzana, at that time Archbishop of Mexico, afterwards Archbishop of Toledo, and subsequently raised to

the dignity of a Cardinal.

"It is," said Moetezuma to Cortes, "now many days since our historians have informed us, that neither my ancestors,

nor myself, nor any of the people who now inhabit this country, are natives of it; we are strangers, and came

hither from very distant parts; they also tell us, that a Lord to whom all were vassals, brought our race to this

land, and returned to his native place. That after a long time, he came here again and

60

found that those whom he had left were married to the women of the country, had large families, and had built towns

in which they dwelt. He wished to take them away, but they would not consent to accompany him, nor permit him to

remain here as their chief; therefore he went away. That we have always been assured his descendants would return

to conquer our country, and reduce us again to his obedience. You say you come from the part where the sun rises,

we believe and hold to be true the things which you tell us of this great Lord or King who sent you hither; that

he is our natural Lord, particularly as you say that it is very many days since he has had notice of us. Be

therefore sure we will obey you, and take you for our Lord in the place of the good Lord of whom you tell us. In

this there shall be neither failure nor deception; therefore, command according to your will in all the country,

that is, in every part I have under my dominions; your will shall be obeyed and done; all that we have is subject

to whatever you may please to command. You are therefore in your own country, in your own house; rejoice and rest

from the fatigues of your journey, and the wars you have been engaged in." He continued to say many other things,

which I omit as being irrelevant.

In another discourse, Moetezuma said to the chiefs and Caciques, whom he had convoked in the presence of Cortes

and himself: -- "My brothers and friends, you already know that your grand-fathers, your fathers, and yourselves,

have been and are the vassals of my ancestors and myself; by them and by me you have always been honoured and well

treated; you

61

have uniformly performed every thing that good and loyal subjects are bound to do for their natural Lords. I

believe also, you have heard from your predecessors, that we are not natives of this country; that they came from

a far distant land; that they were brought hither by a Lord who left them here, and to whom all were subject. A

long time after, this Lord came again, and found that our grand-fathers had married with the women of this country,

had settled and peopled it with a numerous posterity, and would not accompany him back to his country, or receive

him here, as the chief of this. He then went away, saying he would return with, or send such a power as should

overcome them, and reduce them to his service. You well know we have always expected him, and according to the

things. which the Captain has told us, of the King who sent him to us, and from the part he says he comes from,

I think it certain, and you cannot fail to be of the same opinion, that this is no other than the chief we look

for, particularly, as he declares that, in the place he comes from, they have been informed about us. As our

predecessors did not do what they ought to have done by their chief, let us do it, and let us give thanks to our

gods that, in our time has come to pass the event which has been so long expected. As all this is manifest to all

of you, much do I entreat you to obey this great king henceforward as you have hitherto obeyed and esteemed me

as your lawful Sovereign, for he is your natural Lord, and in his place I beseech you to obey this his great Captain."

He proceeded by desiring that such tributes and services as

62

had usually been paid to and performed for him, should in future be transferred to Cortes, as the representative

of their King; saying, that he would himself pay contributions to him, and serve him in whatsoever he should command

The assembled chiefs confirmed the tradition, and replied, "that they had always considered him as their Lord,

and were bound to perform whatever he should command them, and, for this reason, as well as for the one he had just

given them, they were content to do it." (Let this expression, they were content, &c., be noted.) All this, says

Cortes passed before a notary who reduced it to the form of a public act, and I required it to be testified as

such in the presence of many Spaniards.

Cortes, wishing to keep Moetezuma in the error which he supposed him to have fallen into, says in his first letter:

-- "I replied to all he had said in the way most suitable to myself, especially, by making him believe your Majesty

to be the chief whom they have so long expected."

It is surprising that the unvarying tradition of the first occupiers of America having come from the east, should

not have been examined or attended to by Cortes, and that it should have been unobserved by subsequent writers,

and by the introduction of the following notes into the republication of Moetezuma's discourses, is not less

astonishing. "The Mexicans, by tradition, came from the northern parts of the province of Quivira, and the particular

places of their habitations are known with certainty; this affords an evident proof that the conquest of

63

the Mexican empire was achieved by the Tultecas, or people of Tula which was the capital. This was an erroneous

belief of the Indians, because they came from the north; but, had they proceeded from the peninsula of Yucatan

it might with truth be said that they came from the east, with respect to Mexico. In the whole of this discourse,

Cortes obviously took advantage of the erroneous notions of the Indians."

The natives were not mistaken, but Cortes was in error from disregarding their traditions, which, to say the least,

he ought to have kept in recollection and carefully examined when a little industry would most unquestionably have

satisfied him; but, as it was known on the other hand, that the Mexicans and other nations, occupying the desolated

kingdom of the Tultecas, descended from the northern regions, he took no pains to search out from whence and in

what manner they came. This negligence of Cortes, occasioned the error in authors who wrote after him; and it

arose principally from their not having attended to the tradition of the few existing testimonies of the Tultecas,

Chiapanecos, and Yucataneses, and the few historical fragments produced by writers of the greatest authority on

the other continent, who have been similarly condemned, by the most celebrated modern authors.

The Indians carefully preserved the remembrance of their origin, and of their ancestor's early progress from the

voluntary or the forced abandonment of Palestine on the ingress of the Hebrews; but these incidents have been,

in my opinion, erroneously interpreted by authors. -- I will here introduce what

64

the advocate Joseph Antonio Constantini advances on this subject. In the second volume of his Critical

Letters, in that entitled On the Origin of the Americans, he says: "We are indebted to Gemelli for

some valuable information which he obtained, during his residence in Mexico, from Don Carlos de Siguenza y Gonzora,

into whose possession it came, as being testamentary executor of Don Juan de Alva, a lineal descendant from the

king of Tezcuco who received it from his ancestors: this is, therefore, the most authentic document which

Gemelli procured, and he has carefully preserved it in his sixth volume by a plate. This engraving displays a

table or itinerary, on which are delineated the voyages of their progenitors who peopled Mexico; it consists of

different circles, divided into a hundred and four signs, signifying 104 years, which they say their forefathers

spent in their several domiciles before they reached the lake of Mexico; there are numerous and various

representations of mountains, trees, plants, heads of men, animals, birds, feathers, leaves, stones, and other

objects descriptive of their different habitations, and the accidents they met with, but which at present cannot

be understood."

This itinerary I have never had an opportunity of seeing, although very desirous of obtaining that advantage,

nor the book which Botturini says was written by the celebrated Mexican astronomer Huematzin and called by him

Teomoxtli: the divine book; wherein, by means of certain figures, he shews the origin of the Indians,

their dispersion after the separation of nations

65

subsequent to the confusion of tongues, their wanderings, their first settlement in America, and the foundation

of the kingdom of Tula, (which, I suspect from the mistakes of writers is not that of Amaguemecan), and their

progress down to his time, these incidents appear to be the same as those which happened to the Canaanites

generally, and to the Hivites in particular, along the whole coast of Africa, until their passing into America

and arrival at the lake of Mexico. The hundred and four years of domicile described by him were in Africa, and

not for the space of one year each, but of many years, according to the exigence of circumstances in the progress

of population; for it is evident the peopling of the earth after the general dispersion of the human race,

advanced but slowly, as colonies could not be settled without surmounting great difficulties in clearing the

ground from trees and thickets which covered it in every part. This was boring the ground, in the meaning of Votan,

when he says, he went by the road that his ancestors the Culebras had formerly bored.

Calmet, in his dissertation on the country to which the Canaanites retired when they were expelled by Joshua,

concurs in affirming this to be true.

This enlightened writer, after relating various opinions which he proves to be ill-founded, says, the one most

generally received, most consonant with truth, and also conformable to the Gemarra Hierosolemitana, is that which

supposes the Canaanites went into Africa. He adds that Procopius, lib. 2, cap. 10, of the Vandalic War, says they

first fled into Egypt,

66

where they encreased in number, and then pursued their course to the remotest regions of Africa; they built many

cities, spread themselves over the adjacent countries, occupying nearly all the tract that extends to the columns

of Hercules, and retained their ancient language, although in some degree corrupted. To support this opinion,

he adduces a monument erected by this nation, which was found in the city of Tangier: it consisted of two columns

of white marble, with this inscription in Phoenician characters: "We are the children of those who fled from the

robber Jesus, the son of Nave, and here found a safe retreat" (note 18).

These columns may very possibly be the marks that Votan says he left behind him on the road that his ancestors

had bored; but they were considered Apocryphal by Feyjoo, from the expression of the inscription, that, Jesus or

Joshua was the son of Nave, whereas it is stated in the scriptures, that he was the son of Nun; it seems therefore

to have escaped Feyjoo's recollection, that Joshua is indiscriminately called the son of Nave or of Nun in different

places of Holy Writ.

Although we cannot fix to a certain epoch the time of the Canaanites occupying the coasts of Africa, inasmuch as

it did not take place at one period, but gradually, as they found themselves oppressed by the Hebrew wars;

and because many of the Hivites, as we have already said, abandoned their dwellings before Joshua entered

Palestine (note 19). There is no doubt that all these colonies existed prior to the Trojan war, because Greeks

returning from thence found that every part of the coast of

67

Africa where they landed had been already peopled by the Phoenicians. On this point the Greek and Latin writers

agree, according to the testimony of Bochart in his work entitled Canaan; and of Hornius, on the origin of the

people of America. Lib. 2, cap. 3, 4: quoted by Calmet.

The era of the Trojan war is fixed at two hundred and forty years after the death of Joshua. Taking this for

granted, and comparing the epoch when the aforesaid colonies were established in Africa, with that which I shall

presently shew concerning the foundation of the first colony in America by the grand-father of Votan, it will

clearly appear, that, each of the hundred and four signs in the itinerary of Gemelli does not correspond with a

residence of one year, but of many.

This itinerary, supposed by many historians as appertaining to Asia, or the northern parts of America, has been

the means of augmenting our historical difficulties so much, that we encounter nothing but confusion, doubts

and queries: this will be seen by referring to the works of Clavigero, Torquemada and all others who have treated

on this subject. It nevertheless confirms the narrative of Votan, and the suppositions I have ventured to make

as will hereafter appear.

As it has been already proved that Valum Chivim, where Votan landed in his four voyages to the old continent,

is Tripoli in Syria; it is now requisite to examine what was the situation of Valum Votan, from whence he took

his departure.

In order to discuss this important question, which will have the effect of drawing from the depths of obscurity

and uncertainty

68

into which time and revolutions upon the old continent, have plunged those historical records that remained

in ancient traditions; we shall derive sufficient assistance from Calmet in his dissertations before mentioned,

relative to the country in which the Canaanites, when expelled by Joshua and the Judges, his successors took

refuge, as also from the excellence of the Hebrew history.

This celebrated writer recites the opinions of the most classic authors on the discovery of America, and

the origin of its inhabitants, to which, however, he does not always assent, and among them produces that

of Hornius, who, supported by the authority of Strabo, affirms, as certain, that voyages from Africa and

Spain into the Atlantic ocean were, both frequent and celebrated, adding from Strabo, that Eudoxius sailing

from the Arabian gulf to Ethiopia and India found the prow of a ship that had been wrecked, which, from

having the head of a horse carved on it, he knew belonged to a Phoenician bark, and some Gaditani merchants

declared it to have been a fishing vessel: Laertius relates nearly the same circumstance. Hornius says

(continues Calmet,) that, in very remote ages, three voyages were made to America, the first by the Atlantes,

or descendants of Atlas, who gave his name to the Ocean and the islands Atlantides; this name Plato appears

to have learned from the Egyptian priests, the general Custodes of antiquity. The second voyage, mentioned

by Hornius, is given on the authority of Diodorus Siculus, lib. 5, cap. 19, where he says: The Phoenicians

having passed the columns of Hercules, and being impelled by the violence of the

69

wind, abandoned themselves to its fury, and after experiencing many tempests, were thrown upon an island in

the Atlantic ocean, distant many days navigation to the westward of the coast of Lybia; which island, possessing

a fertile soil, had navigable rivers, and there were large buildings upon it. The report of this discovery soon

spread among the Carthagenians and Romans[;] the former being harassed by the wars of the latter, and the people

of Mauritania; sent a colony to that island with great secrecy, that, in the event of being overcome by their

enemies, they might possess a place of safe retreat (note 20).

In another place, Calmet introduces this passage of Diodorus more in detail, saying, that the Phoenicians

having returned from the island, so highly extolled its beauty and opulence as to inspire the Romans with a

desire of making themselves masters of it and settling a colony there. This perplexed the Carthagenians,

who began to fear their countrymen would be enamoured of a fertility so much praised, and abandon their

native soil to settle there. They viewed it, on the other hand, as a safe refuge in the event of any

unforeseen calamity, or, if their Republic in Africa should fall, to which, as being masters of the sea,

they could easily retire to secure themselves and families, more especially as the region was unknown to

other nations (note 21). Aristotle, continues Calmet, in his book of wonderful things, speaking of this island,

says, the Magistrates of Carthage having observed that many of their citizens who had undertaken the voyage

thither, had not returned, prohibited, under the penalty of capital punishment, any further

70

emigration, and ordered those who had remained there to return to their country, fearing, that as soon as the

affair should be known, other nations would endeavour to establish there a peaceable commerce (note 22).

The other voyage in the Atlantic spoken of by Calmet was anterior to the preceding, and is that attributed

to Hercules, who is the supposed author of the Gaditanian columns, and whom Galleo

ranks as contemporary with Moses, and chief of the Canaanites who left Palestine on the invasion of Joshua:

this hero had the surname Magusanus, derived from the Chaldean word Gouz, signifying to scratch, and by

metaphor to pass, from which root, ships and fords of rivers are called Megizze in the Chaldaic idiom; of

his sea voyages, there existed a vestige in the town of West Cappell in the island of Walcheren; it was

the painting of a ship and her captain, who was represented at an advanced age, the forepart of his head

bald, and his face tanned by the sun; he was worshipped as a deity at a temple in the same town, and

sacrifices, according to the Phoenician rites, were offered to him (note 23). There were many other heroes of

this name; but no writer has decided whether to Magusanus or one of his descendants, or whether to a Phoenician

distinguished by the same appellation, we are to attribute the navigation of the Atlantic. Certain, however,

it is, that Diodorus speaks of a Hercules who sailed round the world, and who founded the city of Lecta in

Septimania; but no writer has pointed out its situation (note 24).

With how much reason was the prize awarded to that young

71

prince of the royal house of David who maintained, when disputing in the congress of wise men assembled by king

Ahasuerus, that truth is the most irresistible gift that can be bestowed; for the power of the most absolute

monarch, the stimulating effects of the most generous wine, or the transcendent charms of the most bewitching

beauty, is not sufficiently strong to subdue it.

The coincidence in the memorials of the writers of the old continent, whom I have just mentioned, with the

tradition, as introduced in Moetezuma's two discourses, that the Mexicans came originally from the east;

with the narrative of Votan, with the incidents commemorated by the medal, with the report of Captain

del Rio, and with the figures of the ultramarine deities Isis and Osiris sketched by him in the temple of