Bookshelf | Spalding Library | Mormon Classics | Newspapers | History Vault

|

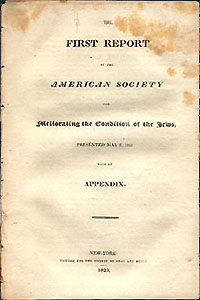

Am. Soc. for Mel. Cond. of Jews First Report (NYC: 1823) |

|

A Star in the West (1816) | News Report on Jewish Colony (1823)

|

Transcriber's Comments

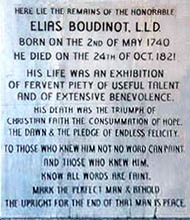

AS is mentioned in the body of this Report, The American Society for Meliorating the Condition of the Jews was organized in New York City on Feb. 8, 1820. A petition for its incorporation was submitted to the New York Legislature, which, on April 14, 1820, granted the incorporation of the society. What the text does not reveal, however, is that the group (largely composed of Protestant ministers) that gathered together on Feb. 8th were previously organized under the name of the "Society for Evangelizing the Jews," in 1816. In 1820, after a few years of feeble existence, the would-be evangelizers were reconstituted with the famed statesman and author, Elias Boudinot, as their first president. The revitalized group met in New York City on Jan. 25, 1820 and added to its previous lackluster evangelizing mission the additional goal of "colonizing the Jews." Probably this secondary purpose was suggested by Boudinot himself, as he was interested in "gathering scattered Israel" in anticipation of the fulfillment of biblical prophecies. Whether or not the group meeting in 1820 shared Boudinot's belief in the American Indians being Israelites, history has left no record (for Boudinot's beliefs concerning the Indians see his 1816 book, A Star in the West.. In deference to the prominent New York City Jewish journalist and politician, Mordecai M. Noah, the Legislature changed the society's name when it approved its incorporation (see M. M. Noah's editorial in the May 13, 1826 issue of his newspaper, The National Advocate). In fact, only a few weeks previous to the group's organization, this same Jewish journalist and politician had submitted his own petition to the Legislature, with the intention of establishing a gathering place for "Israelites" on Grand Island, in the Niagara River, not far from Buffalo. Thus, from its very inception, the shadow of Major Mordecai M. Noah fell over the colonization and proselyting efforts of the so-called "American Society for Meliorating the Condition of the Jews." Its activities during the 1820s are best understood when Noah's own colonization efforts are placed in view alongside the activities of the society.

When Elias Boudinot died in 1821 his will provided the American Society for Meliorating the Condition of the Jews with 4000 acres of land, to establish a colony for converted Jews near Pittsfield, Warren Co., Pennsylvania (about 15 miles south of Jamestown, Chautauqua Co., New York). The society's officers gave up their claim for this remote and undeveloped acreage in exchange for $1000 from Boudinot's executors. During the first months of 1823, a committee of the society was shopping about for a suitable location in western New York, at which to establish Boudinot's planned colony for the Christianized Jews. This was apparently the "negotiation" mentioned in the Richmond Family Visitor and reprinted in the Apr. 5, 1823 issue of Niles National Register. Those sources mention the "Genesee country," while the 1823 Report is a bit more specific, speaking of a spot "easily accessible on the streams of nature or of art" in the "Holland Purchase" (roughly, the land between the Genesee and Niagara rivers). By 1823 the Erie Canal (a stream "of art") had been completed as far westward as Rochester and the next year it reached Newport (now Albion) and Lockport. Probably the tract in the Holland Purchase that the committee was looking seriously at in 1823 was located somewhere between Lockport and Rochester, on or near the partially dug canal. References: George A. Boyd's 1952 book, Elias Boudinot, pp. 261-262; Jonathan D. Sarna's 1981 book, Jacksonian Jew, The Two Worlds of Mordecai Noah, pp. 56-57; ASMCJ Report No. 3, 1823 The Society Establishes Its Jewish Colony Although the society had a sizable amount of money to invest in its Jewish colony its officers were slow to make the final land purchase decision. Before 1823 ended they apparently had given up in their quest to locate a suitable site in western New York and were focusing their attention on making a purchase closer to Albany or even New York City itself. A June 1823 news report in the Plattsburgh Republican indicated that the society might "purchase 20,000 acres... about 25 miles west of Plattsburgh" near the border of Clinton and Franklin counties. This speculative deal never materialized. In 1824 the society's officers finally decided to buy some land in New Paltz twp., Ulster Co., New York. Various events delayed progress on this decision and it was not until 1826 that the society finally decided to use its money to buy a 500 acre farm -- a far cry from the 4000 acres Elias Boudinot had originally intended be dedicated to the project -- Boudinot's plan would have allowed for 80 farms of 50 acres each; while the land decided upon only allowed for 10 such family plots. As things turned out the farm only had 400 acres and minuscule colony was not located at New Platz, but in Harrison, Westchester Co., practically a rural suburb of White Plains. By 1827 the Harrison colony was an admitted failure: the society could not even induce half a dozen converted Jews to take up residence there. In the meanwhile Major M. M. Noah's widely publicized scheme -- for an Israelite gathering on Grand Island -- had come and gone. Thwarted primarily by lack of cooperation from the European rabbis, Noah's grandiose colony (for faithful Jews, "Israelite" Indians, and cooperating Gentiles) died stillborn in the eastern drawing-rooms and in the masonic lodge at Buffalo. There would be no swarms of Jewish colonists descending by the boatload upon Grand Island. Major Noah attended the 1826 annual meeting of the American Society for Meliorating the condition of the Jews but he apparently felt little sympathy for the apethetic results of the Christians' parallel plans for establishing an American refuge for their own Jews. In the end both the Noah plan and the Meliorating Society's plan disintegrated. Noah's dreams depended upon thousands of European Jews flocking to New York with their rabbi's blessings -- a fantasy that even Noah must have known was not a very practical one. Perhaps he felt that the Gentiles would build up Grand Island, while waiting for the anticipated arrival of Jews and Indians. Instead, they poured their resources into Buffalo, a place where at least a few urban Jews did eventually take up residence. The Christians' scheme was hopelessly flawed from the very beginning. There was little hope that they could ever convert Jews in the kinds of numbers necessary to establish a Christian Zion in New York. The ministers' self-constructed mirage of the coming millennial reign of Christ was beyond the vision of faithful Jews and beyond the capacity of converted Jews to leverage into happening. The old biblical prophecies about reclaiming the scattered of Israel and the dispersed of Judah would have to be forgotten for the next few decades. When the time came to resurrect the Zionist plans the goal again became the age old one of Jerusalem and the American gathering became a secular, not sectarian, phenomenon. That is, except for a small band of fanatics with the improbable name of "Mormonites." For them the failed dreams of the Meliorating Society and of Major Noah would be recast as latter day prophecy for a "New Jerusalem" in the west, among those elusive American Indian Israelites. |

|

Elias Boudinot

(under construction) Boudinot, Elias, 1740-1821. Constitution of the American Society for Ameliorating the Condition of the Jews, with an address from the Hon. Elias Boudinot. "Delivered before the society at their first annual meeting, May 12, 1820 and the act of incorporation granted by the legislature of the State of New-York." "Address" p. 2-18. "An act to incorporate the American Society for Meliorating the Condition of the Jews" New York : Printed by Abraham Paul, 1820. Yale University Library: Bg19 Am46m American Society for Ameliorating the Condition of the Jews (Minor Publications of the Society: Annual Reports, etc.) SML, Judaica Collection: Bg19 Am46m Elias Boudinot Delegate and a Representative from New Jersey; born in Philadelphia, Pa., May 2, 1740; received a classical education; studied law; was admitted to the bar in 1760 and commenced practice in Elizabethtown, N.J.; member of the board of trustees of Princeton College 1772-1821; member of the committee of safety in 1775; commissary general of prisoners in the Revolutionary Army 1776-1779; Member of the Continental Congress in 1778, 1781, 1782 and 1783, serving as President in 1782 and 1783, and signing the treaty of peace with England; resumed the practice of law; elected to the First, Second, and Third Congresses (March 4, 1789-March 3, 1795); was not a candidate for renomination in 1794 to the Fourth Congress; Director of the Mint from October 1795 to July 1805, when he resigned; elected first president of the American Bible Society, in 1816; died in Burlington, Burlington County, N.J., October 24, 1821; interment in St. Mary’s Protestant Episcopal Church Cemetery. http://www.virtualology.com/hallofusa/uspresidents/eliasboudinot.com/ Virtualology's Revolutionary War Hall: Elias Boudinot President of the United States in Congress Assembled November 4, 1782 to November 3, 1783 BOUDINOT, Elias, philanthropist, born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 2 May 1740; died in Burlington, New Jersey, 24 October 1821. His great-grandfather, Elias, was a French Huguenot, who fled to this country after the revocation of the edict of Nantes. After receiving a classical education, he studied law with Richard Stockton, and became eminent in his profession, practicing in New Jersey. He was devoted to the patriot cause, in 1777 appointed commissary-general of prisoners, and in the same year elected a delegate to congress from New Jersey, serving from 1778 till 1779, and again from 1781 till 1784. He was chosen president of congress on 4 November 1782, and in that capacity signed the treaty of peace with England. He then resumed the practice of law, but, after the adoption of the constitution, was elected to the 1st, 2d, and 3d congresses, serving from 4 March 1789, till 3 March 1795. He was appointed by Washington in 1795 to succeed Rittenhouse as director of the mint at Philadelphia, and held the office till July 1805, when he resigned, and passed the rest of his life at Burlington, New Jersey, devoted to the study of biblical literature. He had an ample fortune, and gave liberally. He was a trustee of Princeton College, and in 1805 endowed it with a cabinet of natural history, valued at $3,000. In 1812 he was chosen a member of the American board of commissioners for foreign missions, to which he gave £100 in 1813. He assisted in founding the American Bible society in 1816, was its first president, and gave it $10,000. He was interested in attempts to educate the Indians, and when three Cherokee youth were brought to the foreign mission school in 1818, he allowed one of them to take his name. This boy became afterward a man of influence in his tribe, and was murdered on 10 June 1839, by Indians west of the Mississippi. Dr. Boudinot was also interested in the instruction of deaf-mutes, the education of young men for the ministry, and efforts for the relief of the poor. He bequeathed his property to his only daughter, Mrs. Bradford, and to charitable uses. Among his bequests were one of $200 to buy spectacles for the aged poor, another of 13,000 acres of land to the mayor and corporation of Philadelphia, that the poor might be supplied with wood at low prices, and another of 3,000 acres to the Philadelphia hospital for the benefit of foreigners. Dr. Boudinot published "The Age-of Revelation," a reply to Paine (1790); an oration before the Society of the Cincinnati (1793); "Second Advent of the Messiah" (Trenton, 1815); and "Star in the West, or An Attempt to Discover the Long-lost Tribes of Israel" (1816), in which he concurs with James Adair in the opinion that the Indians are the lost tribes. He also wrote, in "The Evangelical Intelligencer" of 1806, an anonymous memoir of the Rev. William Tennent. hen the members of the Continental Congress gathered together to choose a president, they elected Elias Boudinot as the new chief executive (President of the United States in Congress Assembled) on 4 November 1782. Thus he was, in effect, the first president of the United States. The Millennium, the Conversion of the Jews and the Lost Tribes One portent signifying the coming of the millennium was generally regarded as the possibility of converting the Jews to Christianity. What interest was shown in converting the Jews in the Hartlib circle? The question of 'the lost tribe' of Jews was of particular importance because it related to the Indians of the New World. There was a particular problem in the perception of world history as generally perceived in the seventeenth century which was raised by the existence of the Indians. All the nations and races of the world could be demonstrated to have descended (to most people's satisfaction at any rate) from Noah after the Flood. But what about the Indians? It stretched credibility to imagine that they had descended from Noah, swam all the way across to America and promptly forgotten that they were part of God's elect. Yet the alternative possibility, that they were, in some way, descended from before Adam was even more frought with danger. Perhaps, though, they were somehow descended from a lost tribe of Jews sometimes after the Flood and still retained some remnants of their Jewishness. The possibilities raised by their conversion were intriguing and some efforts were made to convert them by Dury and others. See the chapter by Richard Popkin in Greengrass, Leslie and Raylor, Samuel Hartlib and Universal Reformation. Also Gantz (on reading list) With the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars, British millennialists began to preach that, not only was the time ripe for the onset of the millennium, but that man could move events along rather than await divine intervention. The arrival of Joseph Frey, a Jewish convert from Franconia to London in 1801 marks the beginning of the history of the London Society. Baptized in 1798, Frey had received a traditional Jewish education and earned his living as a ritual slaughterer and cantor when he entered a seminary in Berlin and subsequently converted to Christianity. In London, he worked for the London Missionary Society and became the first of many Ashkenazi converts in England to work among the Ashkenazi Jewish immigrants, among the 20,000 Jews who lived in England, two-thirds of them in London who were more accessible than the wealthier, inaccessible Sephardim. 14 Poor, speaking little English, and unemployed, these Jews were Frey's target . He composed Hebrew tracts, directed a charity school, and preached the Gospel to them. After a prohibition against his missionary work was announced in the synagogue, most Jews stopped visiting him and refused to send their children to the Free School he had set up. Receiving little financial support from the London Missionary Society, in 1809, he and others formed the London Society for Promoting Christianity Amongst the Jews. In 1815, the society came under the sole auspices of the Church of England, and the following year, after a short but colorful career, Frey was dismissed for adultery and sexual misconduct. |

Return to top of the page

Return to: Oliver Cowdery's Writings | Oliver Cowdery Home Page

last revised July 4, 2002