MORDECAI M. NOAH and the Mormon ZION

Part 1: 30 Ararat-Mormon Parallels Part 2: Source Texts/Resources

Part 3: M. M. Noah & Oliver Cowdery Part 4: M. M. Noah & the Masons

|

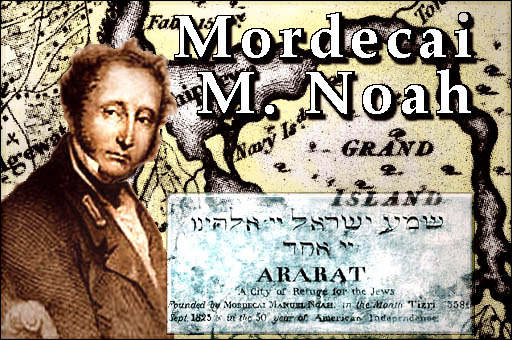

"I, Mordecai Manuel Noah... by the grace of God, Governor and Judge of Israel, have issued this my proclamation, announcing to the Jews throughout the world that an asylum is prepared and hereby offered to them..." (M. M. Noah, 1825) Who Was Mordecai M. Noah and What Was "Ararat"? Major Mordecai Manuel Noah (1785-1851) was a noted American journalist, playwright, diplomat, New York politician, and Jewish advocate. In 1825 this utopian proto-Zionist proposed and planned a gathering of the world's "Israelites" to western New York state in order to establish a great city and a powerful theocracy -- for the protection and advancement of God's " chosen people." Although the goals of Noah's 1825 project was never realized, many elements of his "City of Refuge" plan for the restoration of Israel were revived, Christianized, and implemented by the early Mormons in their own attempts to build a North American "Zion." The Mormons originally planned the building of their "City of Refuge" at Independence, Missouri, but that goal was beset by various obstacles and they moved its location -- first to Kirtland Ohio, then to Nauvoo, Illinois, and finally, to Salt Lake City in Utah. Major Noah did not live to see his dreams for an Israelite gathering come true, either in the New World or in the Old. By the end of his life he, like the Mormons, had shifted his sacred geography but had not lost track of his original mission. Quietly abandoning his earlier hope to incorporate the American Indians into his Israelite utopia, Noah became a proto-Zionist whose eyes were finally fixed on Turkish Palestine as the proper place to gather his dispersed brethren. Mordecai M. Noah was not unaware of the Mormons' imitative gathering activity on their own behalf and for the restoration of the supposed Israelite Indians. As a newspaper editor he now and then directed a few choice words in the direction of these johnny-come-lately Saints, but mostly he simply chose to ignore them and their Christianized mutation of his old Grand Island scheme. Had Noah himself taken more trouble to respond to the Mormons' zionic activities, perhaps their mimicry of his own failed "Restoration" would not have gone unnoticed for many decades. Noah avoided the chagrin of making such an admission and today practically everybody has forgotten both him and his land promotion of 1825. Now, 175 years later, the time has arrived for people to take a new look at Major Mordecai M. Noah and his proposed gathering of Israel to "the land shadowing with wings, which is beyond the rivers of Ethiopia," -- which he translated to read: "the land of the (American) Eagle!" Biographical Sketch of M. M. Noah: He was born in Philadelphia on July 19, 1785. His father was Manuel M. Noah, a Revolutionary War champion who had married Zipporah Phillips (of Portuguese Sephardic Jewish lineage) the year before. In 1795 Mordecai's mother died and he raised was thereafter primarily by her father, Jonas Phillips, a Prussian Jew who had immigratedto Charleston, South Carolina in 1756. While he was yet a young man the ever-ambitious Mordecai retraced his grandfather's footsteps to Charleston, where he hoped to study law, gain experience in journalism, and get a start in party politics. The youthful "Major" (in the Pennsylvania militia) found the both sensible and political climate in Charleston much to his liking and he was pleased to use his grandmother Phillips' Portuguese ancestry to establish himself socially among the aristocradic Sephardi of that city's Congregation Beth Elohim. Unfortunately, Mordecai's stay in the South appears to have infected his thinking with less than appreciative opinions of ante-bellum Black people he encountered there. At the same time, and rather incongruently, he also became an outspoken southern journalist who championed both American democracy and the cause of Jewish people world-wide. The verve and wit of Noah's patriotic "Mulek" articles in the Charleston Times, (generally supporting Madison's administration) did not go unnoticed in the capital city as the young nation entered the War of 1812. Noah's declared zeal on behalf of Madison's policies, a bold petition written to that same head of state, and an accompanying sheaf of recommendations from influential patrons (gathered as early as 1810-11) helped him gain an appointment as the U.S. Consul to the Kingdom of Tunis in 1813. The next year the administration sacked him, ostensibly for allowing his religious identity to color his dealings with the Moors and his free spending of government money in helping to free certain American prisoners held at Algiers. A few months after this disapppointment Mordecai moved to New York City, where he engaged in a letter-writing campaign to reestablish his good name, advanced his career in journalism, and continued to promote himself in partisan politics. Prior to his return to the city which had been a temporary home in his youth, the mature Mordecai had the good fortune to see his uncle, Naphtali Phillips, become the proprietor of the National Advocate, the favorite paper of New York's anti-Federalists and the political mouthpiece for that city's "Society of Tammany" (the regional political machine of the Democratic-Republicans). Mordecai soon became the chief editor at this prestigious enterprise, and he remained the editor (or an associate editor) at one or another of sundry New York publications for the remainder of his life. In 1820 Major Noah declared his candidacy for Sheriff of New York and the following year received an appointment to the same, a post he held until losing that dignity amid the intra-party feuding accompanying the election of 1828. In the meanwhile Noah had shifted his political ground and in 1826. he resigned his editorship at what was by then George White's National Advocate. In 1829 the "Clintonian" clique within the New York Democratic-Republicans befriended the Major and handed him a political plumb: the office of Surveyor and Inspector of the Port of New York. During these Big Apple political squabbles in the 1820s Mordecai M. Noah progressed from being a declared "Bucktail" enemy of Governor Dewitt Clinton, to tacitly supporting some Clintonian programs (such as the completion of the Erie Canal), to eventually allying with Clinton's Democratic faction in the 1829 campaign to send Andrew Jackson to the White House. Noah's political patron and mentor, Martin VanBuren, had accomplished some similar political footwork in order to become Jackson's running-mate. Throughout this entire period (whether as a collaborator with Tammany Hall or as its opponent) Major Noah remained an outspoken pro-slavery man and a chief adversary of the abolitionists. Ever active in local Jewish affairs, Noah delivered what became a famous speech in 1818, when he helped supervis the consecration of the Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue in New York City. Noah's speech related the history of Jewish persecution around the world and argued that the Jewish people must be established as a nation with their own government, in order to avoid future oppression. The rhetoric expressed by Noah's in his 1818 speech anticipated the problems of growing anti-Semitism in Europe and the precarious position of Middle-Eastern Jews standing on the sidelines of the Greek rebellion against the Turks. Major Noah's 1818 oration also foreshadowed his still undisclosed plan to play midwife to a great gathering of Jews who might some day build an agrarian theocracy in upstate New York: "Jews must be turned aside from the crooked paths of traffic, miscalled commerce, to industry and agriculture..." Mordecai M. Noah's 1818 call for a new program among the Jews was not just empty oration. By 1820 he was petitioning the New York Legislature to grant him an extensive parcel of land on Grand Island in the Niagara River, so that he might establish there a new Jewish homeland where "Israelites" of all types might find refuge and opportunity. Grand Island, along with several other, smaller islands located upstream from Niagara Falls theoretically became part of the United States in 1783, following the end of the Revolutionary War. The British troops stationed along the Ontario frontier continued to occupy the banks of the Niagara until 1796, when the Iroquois Nation claimed possession of the islands in the River. The State of New York recognized the Iroquois claim, but both the national and state governments were eager to take permanent possession of the area as the War of 1812 drew to a close. On September l2, 1815, in order to forstall any future Canadian attempt to seize this borderland property, New York paid the Iroquois $1000 for Grand Island and its smaller insular neighbors. That minor bit of geographic news would eventually catch the imaginative attention of Mordecai M. Noah in New York City. Following his 1826 political divorce from the Tammany Democrats who controlled the National Advocate, Noah left its editorial offices in July of that year and immediately founded his own, independent New York Enquirer. By early 1829 Noah had drifted into the camp of his previous rivals, the Clintonians, and that May he merged his newspaper with the New York Morning Courier, a anti-abolitionist Jacksonian paper previously published by men like John B. Skillman and James Gordon Bennett. At that time the Courier was managed by James Watson Webb. For several years he and Major Noah continued to operate the paper on good terms, but Noah's friendly feelings for Wood abated during the fight within the Democratic Party over whethe ror not to renew the charter of the United States Bank. Having finally abandoned his seven year alliance with the Jacksononians, Mordecai M. Noah drifted into the nascent Whig movement and in September of 1833 he again founded his own New York paper, supporting that growing political amalgamation. His new enterprise he called the Evening Star. This was an uneasy transformation on Noah's part and, although he won the friendship of partisans like Thurlow Weed of Rochester, the Major was never fully at home among the exuberant abolitionism and anti-Masonry which so frequently typified the early Whigs. Noah's career as an editor-publisher lasted until 1842 when the Star was discontinued. He managed to continue his career in journalism and politics to a degree, but all of that ended suddenly in 1851 when Mordecai died of a stroke. By that time Major M. M. Noah was arguably the best-known Jew in America. Noah's 1825 Plans for the Gathering of Israel As early as 1818 Mordecai Manuel Noah was of the opinion that there was no place in the Old World where Jews had a hope of achieving equality prior to their re-establishment in Israel at some time in the unknowable future. Instead, he turned his attention to the many advantages then available to settlers of all kinds in democratic America. Before 1820 Major Noah decided that the undeveloped western region of New York state offered the best promise for a successful relocation of his scattered people. Noah was not alone in pursuing this sort of idealistic proto-Zionism. The reigning Democrats of his day strongly favored an increased immigration into the young nation and the nationalistic yearning which was later to be called "manifest destiny" was already tempting some imaginative Americans to speak of importing organized companies of Jews to settle its western borderlands. More substantial plans were initiated by England and France to send some of their Jewish residents to proposed new homelands in the Caribbean or in Central America, but, for one reason or another, none of these programs were ever brought to fruition. Noah's interest in Grand Island was probably sparked when New York Governor Clinton and his Attorney General, Martin Van Buren, implored the Legislature to authorize the removal of a couple hundred squatters who had taken up residence on the island after the Iroquois gave up their claims to the place in 1815. The Assemblymen in Albany passed the requested eviction act in April 1819 and empowered the Sheriff of Niagara County to organize the local militia and drive out the undesireables. This eviction was accomplished by the beginning of 1820. That same year the Legislature took up consideration of splitting off the Niagara region south of Buffalo and Grand Island in order to form a new county which could meet the needs of the expected population increase at the western terminus of the Erie Canal (then still under construction west of Rochester). Mordecai M. Noah was both an informed journalist who kept close track of interesting news reports and an experienced politician who kept one ear attuned to any new developments coming out of Albany. He quickly recognized the unique opportunity then arising on the big island downstream from Buffalo, and, seizing the opportunity, he petitioned the Legislature to grant him a land patent on the recently vacated island. Noah's move was premature and was probably doomed to failure in a Clinton-loving state Assembly which every year added new members from the growing west. The Clintonians on both the eastern and western ends of the state expected a lucrative western land development to follow the completion of the Erie Canal out to Buffalo by the mid-1820s. These political minds were not particularly inclined to dispose of large amounts of frontier property for a song. The anti-Clintonian big city Jew lost his bid to become chief proprietor of the uninhabited forests encircled by and unbridged river at the antipodes of eastern "civilization." Major Noah was undaunted by this minor setback. Perhaps his land-grabbing attempt was more a publicity stunt than it was a true attempt to take possession of the island all by himself. The slow but inevitable progress of the Erie Canal westward matched the New York Jew's own measured evolution away from his old anti-canal rhetoric. He gradually came to the inescapable conclusion that this new waterway, extending from the Hudson to the Great Lakes, would make a huge, positive impact upon western New York. He saw Erie County created in 1821 and the subsequent commencement of construction at the western end of the canal in Buffalo. The plan then was to join this Buffalo segment of the canal to the westward extension, somewhere along the Niagara escarpment by 1825. A year before that date the boom-town of Lockport had sprung up at the junction point and the state surveyors had completed the sub-division of nearby Grand Island into dozens of 200 acre lots. Well before that time Major Noah had already formulated his plan to attempt the establishment of an Israelite colony on the island. By early 1825 he was deeply engaged in his selling this land development scheme to several of his friends and associates. The Legislature opened the bidding in a public auction to dispose of the State's lands on Grand Island on June 3, 1825. One of Major Noah's business partners, Samuel Leggett, purchased 2,555 acres in Noah's behalf. According to contemporary newspaper reports, twelve other parties also came away from the land auction with deeds to Grand Island lots in their pockets: Cornelius Masren, Herman H. Bogert, John G. Camp, Peter Smith, John Knowles, Alvin Stewart, Levi Beardsley, James O. Morse, S. R. Warren, C. R. Webster, Dudley & Gregory, and James Carmichael. Of these partners only Sheriff Camp of Buffalo was a resident in the far west of New York. He was perhaps one of those most directly involved in Noah's development scheme. The other men in the list were also involved with Noah's plan to one degree or another. A news report of the June auction made this announcement: It is said Mr. Noah's object is to accommodate his brethren, the Jews, many of whom are wishing to emigrate to this country, and to locate in a body, in sufficient numbers to form a colony or city, by themselves. Grand Island has been selected for this purpose, and it is stated in the Albany Gazette, that the corner stone of a city will be laid on this island, with suitable masonic and religious ceremonies, in the course of the present summer, probably about the time when the canal is completed and in operation. Major Noah's plan to make Grand Island into a "City of Refuge" was finally afloat in a sea of optimistic financing, and so was his own "rescue ark," a picture of which sailed the ocean of ink poured out in printing the masthead of his New York Enquirer. Noah's New York City paper continued to feature the Noah's Ark picture for months after the settlement plan became a condeded failure. During the October 1825 dedication celebration which opened the Erie Canal to commercial traffic, Moredcai M. Noah -- ever the theatrical showman -- also sponsored the sailing of a sizeable real ark filled with wild western animals, all the way from Buffalo to New York City.

Even after Grand Island's failure, M. M. Noah still retained Noah's Ark in his newspaper masthead. In anticipation of his staging a gala dedication ceremony for the new land speculation scheme, Major Noah ordered the cornerstone for his enterprise from the distant quarries of Cleveland. Its inscription read: "Ararat, A City of Refuge for Jews, Founded by Mordecai Noah in the month Tizri 5586, September 1825 and in the 50th Year of American Independence."At the end of the summer of 1825 Major Noah and his private secretary journeyed to the region of his intended "happy land" of "Ararat," and there oversaw the pretentious dedication ceremony for the new refuge (jointly held in the Buffalo Masonic Lodge and at St. Paul's Episcopal Church in that town. Noah's visionary plan, his grandiose personality, and his apparent thirst for personal theocratic power were not well accepted by prominent Jews of his day. The plan elicited interest and discussion, but without substantial support from the leaders of European Jewry a practical immigration program could never be initiated, much less carried to fruition. The Noah program was widely ridiculed in the European Jewish press and no Jews from that part of the world moved to Mordecai's "happy land. The Failure of Noah's "Ararat" The would-be "Judge" of a new nation saw his financial and political backing melt away in New York City, while his Masonic support in upstate New York faded amidst the anti-Masonic chaos of the William Morgan affair in 1826. The U. S. and Canadian Indian tribes showed no signs of joining Noah's "Israelite" undertaking, and the entire scheme quickly turned into a dismal failure. Probably the deciding factor against Major Noah's scheme was the disinterest and criticism expressed by Jewish leaders in Europe. Writing in protest against Noah's 1825 project, the Grand Rabbi De Cologne in 1826 said, "inform Mr. Noah, that the venerable Messrs. Hiershell and Meldonna, chief rabbis at London, and myself, thank him, but positively refuse the appointments he has been pleased to confer upon us. We declare that, according to our degrees, God alone knows the epoch of the Israelitish restoration; and he alone will make it known to the whole universe, by signs entirely unequivocal; and that every attempt on our part, to re-assemble with any political-national design, is forbidden, as an act of high treason against the Divine Majesty." Given the almost inevitable refusal of the European Jewish leaders to sign on to Major Noah's emigration plans, the question might well be asked, "Just how serious was Noah about bringing the whole project to a successful outcome?" Is it possible that all of his lofty rhetoric and grandiose claims were merely a smoke-screen behind which Mordecai M. Noah was launching a great land speculation scheme -- a scheme designed primarily to enrich himself and his associates? This interpretation of his motives and methods was voiced in the 1825 response by the editor of Niles Weekly Register published in Baltimore: "It is very possible that this speculation may succeed, so far as to fill the pockets of Mr. Noah and his associates -- which, it is plainly evident, is the corner stone of the project just developed..." Writing a few years later, Mormon journalist W. W. Phelps was even less sympathetic in his assessment of Noah as being "a man [who] has failed to dupe his fellow Jews, with a New Jerusalem on Grant Island... to wheedle money from the Jews to fill his own pockets..." Had M. M. Noah in 1825-26 exercised less headline-grabbing theatrics and more productive communication with the European Jewish leaders, the basics of his plan might well have been carried to success in Jacksonian America. But that alternative would have included Noah simply as the promoter of a probably non-theocratic Jewish colonization, almost certainly shorn of its Israelite Indians and his solicitations of annual monetary payments from overseas. The very self-serving ostentation and staged media hoopla Major Noah counted upon to give his gathering scheme some free world-wide publicity ended up dooming the project before it ever got off the ground. The Masonic Connection W. W. Phelps (the man who accused Major Noah of trying to dupe his fellow Jews), had gained his own pre-Mormon reputation in western New York as the crusading editor of the anti-Masonic Ontario Phoenix of Canandaiga. At least part of the vitrolPhelps directed at Major Noah as late as 1835 probably came from the fact that Noah was a leading Masonic promoter, while Phelps expressed himself as being bitterly against that fraternal society and "secret combinations" of all kinds. Phelps' rhetoric typified the feelings of many of the puritanically-inclined former Yankees who had settled western New York. The same "rise of the common man" which helped put Andrew Jackson into the Presidency in 1830 also helped spawn the distrust and antagonism western New Yorkers heaped upon the Freemasons after 1826. It very likely that most (if not all) of Major Noah's twelve investment associates in the Grand Island scheme were also Freemasons. At the very least least, that identification of their private affiliations would fit in quite nicely with the blatantly Masonic trappings of Noah's Sep. 15, 1825 activities at St. Paul's Episcopal Church in Buffalo and the Masonic Lodge of that place. The editor of Niles Weekly Register, in his article of Oct. 1, 1825, called Major Noah's calendar dating of the Grand Island dedication ceremonies "a strange mixture of Christianity and Judaism." He might well have extended that estimation to the whole of the September 15, 1825 Jewish-Masonic-Christian rendezvous in Buffalo. It would have been practically impossible for Mordecai, the Jewish leader from New York City, to have gained his commanding access of St. Paul's church in Buffalo without the specific cooperation and recommendation of Episcopal leaders in both cities. In those days it would have been far more likely for wealthy American Episcopalians, Diests and Jews to have become important Freemasons than it would have been for Christian primitivists and Calvinists drawn from the "common people." It is altogether likely that many of Mordecai M. Noah's associates (as well as the expected city lots buyers) involved in his Grand Island development plan came from the former social set and not the latter. The ruling, professional, and commercial elite class of New York State in the 1820s and 1830s was largely comprised of Episcopalians, Diests and Jews of Masonic affiliation who were not pious descendants of New England Puritans. Yet it was precisely the pioneering posterity of the latter group which made up most of the population of western New York. Whitney R. Cross, in his 1950 book The Burned-Over District, documents well the mentality and religious tendencies among this pioneer population. Cross's chapter 6 ("The Martyr") deals with the rise of anti-Masonic fervor in upstate NY in the late 1820s. In chapter 6, on page 115, he tells of the Burned-over District's New Englander pioneers' grass-roots reaction against the Masonic institition: "Increasingly it appeared that Masons held a monopoly of offices [in western NY] ... When local citizens' committees induced the state legislature to consider a special investigation, theur resolutions met such smaking defeats that a gigantic [Masonic] conspiracy seemed the only logical explanation. If corruption in high places extended over the whole state, surely the people must act..." Major Noah's imposing Masonic dedication ceremonies for the Grand Island project may have attracted the awe of western New Yorkers, but they also no doubt aroused their ire as well. Such pomp and ceremony may have been tolerable at such occasions as Dewitt Clinton's 1823 great conclave of Freemasons in New York City to extol the Erie Canal, but "out west" among the "common folk," it was less esteemed. In this regard, Major Noah's timing for his 1825 dedication could not have been worse. Most of the western New York Masonic lodges broke away from their eastern "City Grand Lodge" counterparts in 1823, throwing "blue lodge" Freemasonry west of Syracuse into a turmoil. Months before M. M. Noah arrived at Buffalo to orchestrate his 1825 dedication extravaganza, many of the Masons in the west (under the leadership of Joseph Enos and S. Van Rensselaer of Canandaigua) had already grown suspicious and resentful of their eastern counterparts (who remained loyal to Grand Master Martin Hoffman of New York City). Then, as though to roguishly compound that intra-fraternal problem many times over, in late 1826 the whole "Burned-over District" was caught up in the anti-Masonic turmoil which followed the Masonic abduction and probable murder of William Morgan -- the man whom Whitney R. Cross called "The Martyr." It did not matter to the common man in the west that the "Morgan Affair" was primarily attributable to the break-away "Country Grand Lodge" Masons. The westerners were soon tarring all Masons with the same blackened brush -- and that would have included Mordecai M. Noah as well. Western New York After the "Morgan Affair" In August of 1831 James Gordon Bennett, an associate editor (along with Mordecai M. Noah, until Noah left early in 1833) at the NY Morning Courier and Enquirer, paid a visit to the Palmyra area of western NY, probably partly for the purposes of doing some investigative reporting on the Mormons in that place. His articles on this subject appeared in the Courier on Aug. 31 & Sep. 1, 1831. In making his report Bennett editorialized as follows: "About this time [late 1820s] a very considerable religious excitement came over New York in the shape of a revival. It was also about the same period, that a powerful and concerted effort was made by a class of religionists, to stop the mails on Sunday to give a sectarian character to Temperance and other societies... and to organize generally a religious party, that would act altogether in every public and private concern of life. The greatest efforts were making by the ambition, tact, skill and influence of certain of the clergy, and other lay persons, to regulate and control the public mind... to turn the tide of public sentiment entirely in favor of blending religious and worldly concerns together. Western New York has for years, had a most powerful and ambitious religious party of zealots, and their dupes.... The singular character of the people of western New York -- their originality, activity, and proneness to excitement furnished admirable materials for enthusiasts in religion or roguery to work upon.... This general impulse given to religious fanaticism by a set of men in Western New York, has been productive among other strange results of the infatuation of Mormonism."Bennett's 1831 articles might be called "anti-religious" as well as "anti-Mormon," in the same way that his later printed attacks upon his old associate at the Courier and Enquirer could be called "anti-Semitic" as well as "anti-M. M. Noah." In his zeal to put down the reactionary popular piety of western New York in the early 1830s, Bennett avoided the then potentially self-embarrassing topic of anti-Freemasonry altogether. Had Bennett extended the scope of his 1831 articles only slightly, he might well have said that the anti-Masonic movement sprang from the same "class of religionists" who were so upset about Sunday mail deliveries and their neighbors' over-indulgence in ardent spirits. Indeed, historian Whitney R. Cross used the story of these same Burned-over District "religionists" to link his chapter dealing with the anti-Masonic William Morgan and his subsequent chapter concerning the early Mormonism of Joseph Smith, Jr. Bennett's designated "class of religionists" would have been little interested in promoting the seeming self-aggrandizing land sales schemes of big city politicians, Freemasons, and Jews like Mordecai M. Noah. It was, however, this same "class of religionists" who gave rise to a singular group of Christians who were ready to embrace practically every element of Noah's "Israelite Gathering," save that of Noah himself being the leader of a Jewish and American Indian "chosen people." As early as 1800, breakaway Congregationalists in Middletown, Vermont had begun to teach that ordinary Yankee farmers might well be Israelite descendants themselves! These modern "Israelites" were led by the cultist Nathaniel Wood, who taught that they were "under the special care of Providence; that the Almighty would... specially interpose in their behalf..." According to Wood and his followers, a New Englander's "Israelite" ancestry could be determined by the supernatural motions of a witch hazel diving rod pointed at his or her person. Such odd Southcottian notions affirming alleged Israelite ancestry remained fixed within the minds of certain New York pioneers -- indeed, among some of those very same believers whom Bennett denounced as a fanatical "class of religionists." The primitive Anglo-Israelite sentiments of these "religionists" were no doubt originally based upon the prophecies of Richard Brothers, who in 1795 published a widely-circulated book promoting his improbable Israelite-European descent claims (Revealed Knowledge of the Prophecies..., London, Albany, etc.). All things considered, it is not at all surprising that in the late 1820s the leaders of a certain sect of self-proclaimed modern "Israelites," native to the "Burned-over District," conspired secretly to hijack, Christianize, and implement Major Noah's failed "Israelite Gathering." The Aftermath of the "Ararat" Failure In the fall of 1833 Mordecai M. Noah finally sold his share of Grand Island acreage to L. F. Allen, Stephen Waite, and other timber-cutting investors under the auspices of "The East Boston Company." These investors of 1833 purchased a total of nearly 16,000 acres of land on the island from a various owners, at about five dollars per acre -- considerably below what Major Noah must have originally anticipated in a lucrative disposal of his Ararat "city lots." A newspaper article reprinted in the Chardon Spectator of Geauga Co., Ohio on Dec. 28, 1833 tells how these Bostonians planned to cut the island's white oak groves and to transport the timber to shipyards on the east coast via the Erie Canal. In describing the saw-mill village which had sprung up on the island, the article reported "This valuable property has lain dormant and almost forgotten, since the renowned Jewish city of Ararat was founded by Judge Noah, on the very site of which the present proprietors are erecting their establishment..." As late as 1837 Noah was still supporting the idea that the American Indians were his fellow Israelites (for details see his Discourse on the Evidences of the American Indians being the Descendants of the Lost Tribes of Israel... NYC, 1837,); but by then he had given up gathering these native tribes with his own Jewish race. Having abandoned this utopian amalgamation of diverse peoples, Major Noah embraced the more widely-held Zionist view that a direct colonization of Turkish Palestine was the only way to provide a permanent refuge for the Jews. By 1844 he was pleading in his Discourse on the Restoration of the Jews for the Christian world to help the Jews resettle in their original Middleastern homeland. If Mordecai M. Noah temporarily lost pious prestige and pecuniary profit in the aftermath of his Grand Island development scheme, he soon recovered and was able to restablish his previous reputation as a man of literary distinction and political influence. Bits and pieces of his old Jewish emigration plan saw fruition, both in America and, eventually, in what is today the nation of Israel. The question which remains is whether or not even more "bits and pieces" of his "Israelite Gathering" project were collected and promoted by the early Latter Day Saints. The Mormon Zion In March of 1831, less than a year following the founding of the Mormons' "Church of Christ" in upstate New York, David Staats Burnet, an Ohio newspaper editor and an admirer of religious reformer Alexander Campbell, published this interesting remark: "[the Mormons believe] that treasures of great amount were concealed near the surface of the earth, probably by the Indians, whom they were taught to consider the descendants of the ten lost Israelitish tribes, by the celebrated Jew who a few years since promised to gather Abraham's sons on Grand Island, thus to be made a Paradise."The "celebrated Jew" spoken of here is, of course, Mordecai M. Noah. Burnet was almost certainly the first writer to publicly associate the Mormons' beliefs and practices with the celebrated Major Noah and his views concerning Indian origins. Rev. Burnet limited the tie he perceived between the two parities to a single item: the presumed "Israelitish" origins of the American Indians. Implicit in Burnet's statement is the fact that both Major Noah and the earliest Mormon leaders had expressed these similar Indian origin views at about the same time and place -- that is, western New York in the latter half of the 1820s. This Israelite claim for Indian origins was not unique to Major Noah and the Mormons, of course. It was a widely-held belief which had been previously promoted in the popular press by such religious writers as James Adair, Elias Boudinot, Josiah Priest, and the Rev. Ethan Smith of Poultney, Rutland Co.,Vermont. Mordecai Noah's plans for an Israelite gathering on Grand Island and his advocacy for the Israelite origin of the American Indians were well known throughout western New York after the fall of 1825. Reprints of his own and others' articles on this subject appeared in the newspapers published in and around Joseph Smith, Jr.'s home town of Palmyra, New York throughout the mid-1820s (see, for example, the bibliographic information provided in Marvin Hill's "The Roll of Christian Primitivism..." (PhD Dissertation, University of Chicago, 1968, p. 98.; Robert N. Hullinger, Joseph Smith's Response to Skepticism (St. Louis: 1980) pp. 54-56 & 65-67; Dan Vogel, Indian Origins and the Book of Mormon (Salt Lake City: 1986) pp. 42-43, 56; Steven Epperson, Mormons and Jews... (Salt Lake City: 1992 ) pp. 12-13; and H. Michael Marquardt & Wesley Walters, Inventing Mormonism (Salt Lake City: 1994) p. 45). Joseph Smith, Jr. was not the only early Mormon leader who was living near Major Noah's hoped-for "City of Refuge" during the mid-1820s. Oliver Cowdery, one of Joseph's primary associates in establishing Mormonism, was said to have been a pedestrian pamphlet peddler in western New York during this same time period. He may well have been living in Niagara, Orleans, or Genesee counties, practicing the printing trade, while Mordecai M. Noah was first purchasing his "city lots" on nearby Grand Island. Writers commenting on the parallel between Noah's views regarding Indian origins and the views held by the early Mormons have overlooked Oliver Cowdery's probable proximity to Major Noah's utopian project in western New York during the mid-1820s. On the other hand, Joseph Smith, Jr.'s nearness to these events and his evident interest in the subject are well documented. In his on-line essay Challenging the Book of Mormon Stephen F. Cannon states: "...some of the foundational ideas of the Book of Mormon may have emanated from [Smith's reading of local newspapers]... A prime example of this is a reprint of an address given by one Mordecai M. Noah. Published in the Wayne Sentinel on October 11, 1825 (five years before the publication of the Book of Mormon), this address puts forth Noah's theory on the Hebrew origin of the American Indian, "Those who are conversant with the public and private economy of the Indians, are strongly of (the) opinion that they are the lineal descendants of the Israelites, and my own researches go far to confirm me in the same belief." Of course, the central theme of the BOM is that of tracing migrations of Israelites to ancient America, and one of the families becoming evil, being cursed with a dark skin, and degenerating into the progenitors of the American Indian."A fact which the previous writers on this topic seem to have overlooked is that the early Mormons' social and religious programs resembled Major Noah's 1825 project in many, many other ways other than both parties simply subscribing to the alleged Israelite origins of the American Indians. The current writer has explored a few of these additional parallels in his on-line remarks regarding Mordecai M. Noah and the Mormons. The essay posted there says that "The location of the "New Jerusalem" Israelite gathering place spoken of in the Book of Mormon (Ether ch. 6 -- 1830 ed.) was not clearly defined. The earliest Mormons thought of it as being situated 'on the borders by the Lamanites' in 'this land' (North America) and most likely within the western bounds of the United States." A close inspection of the Mormon plan to initiate an Israelite "gathering" and a "restoration" among the American Indians in 1830-31 reveals literally scores of parallels with Major Noah's similar 1825 plan to restore the ancient society of the Jewish people in North America -- a project which, as Noah detailed it, was actually a plan to gather and restore the entire presumed nation of Israel (including the American Indians). The primary difference between the Mormon project and Major Noah's prototype was that at a very early date the Mormon founders determined that the Jews and the major portion of the "Ten Lost Tribes" should be gathered and restored at Jerusalem. Only the descendants of the Israelite Patriarch Joseph and their associates would gather to a new "City of Refuge," which they would erect in the United States. By late 1830, President Jackson's removal of several of the southern Indian tribes to lands west of the Missouri River made the far-off "borders" of those dispossessed people a more promising spot for that new holy city than the largely bypassed Grand Island of M. M. Noah. PART 1: Ararat-Mormon Parallels |

Return to Top of This Page

Return to: Spalding Research Project (Introduction)