MORDECAI M. NOAH and the Mormon ZION

Introduction: Who Was M. M. Noah? Part 1: 30 Ararat-Mormon Parallels

Part 2: Source Texts and Resources Part 3: M. M. Noah and Oliver Cowdery

|

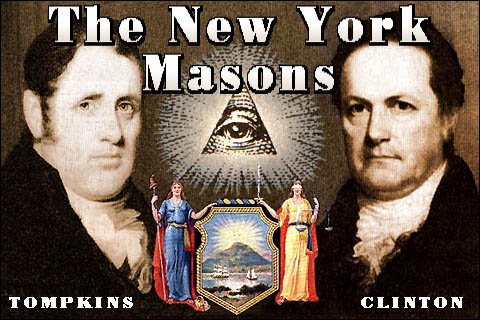

-- Part Four -- "Doubtless De Witt Clinton was wholly innocent of guilt, but his situation was not the less clearly one of conflict between his Masonic and his social and religious duty." (John Quincy Adams, 1845) (speaking of William Morgan's abduction) Mordecai M. Noah: Royal Arch Mason Sephardic Jews and American Freemasons The Jewish Kahal Kadosh (Congregation) Beth Elohim was formed in Charleston, South Carolina in 1749, ten years after a lodge of the "Ancient and Honorable Society of Free and Accepted Masons" was organized under John Hammerton its first Master. It is no coincidence that both of these events happened in Charleston at such an early date. The 1669 "Fundamental Constitution" for the British Colony of Carolina" was written by the English philosopher John Locke. He added in guarantees of societal and religious freedom which soon made the colony (and particularly its main port Charleston, est. 1670) a haven for persecuted worshippers such as Hugenots from France and Sephardic Jews fleeing from Portugal and Brazil. The port of Charleston was also linked by ties of citizenship and commerce to the British West Indies, where the European-evolved Masonic Rite of Perfection (later Scottish Rite Freemasonry) was first introduced to the New World by Stephen Morin (at Kingston and San Domingo, 1761). The new Perfectionist (later Scottish Rite) lodges were next set up in French America (at New Orleans, 1763) and in the American British Colonies (at Albany, 1767 and Philadelphia, 1782). Finally, this new order of Freemasonry was instituted at Charleston, South Carolina in 1783. Many of the Charleston Lodge members were Jews and/or continental Europeans. In 1786 Frederick the Great of Prussia issued "Grand Constitutions" which brought "The Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite" into formal existence. From that date the Charleston Lodge, with its many Jewish members, can rightly be labeled "Ecossais" -- what English-speakers termed the "Scottish Rite." The growing predominance of the Charleston Lodge was made evident on May 31, 1801, when eleven of its members met in that city to establish (under the authority of high Mason Colonel John Mitchell and the Episcopal Rev. Fredrick Dalcho) The Supreme Council of the 33d Degree [Scottish Rite] for the United States of America. This Charleston "Supreme Council" became the parent body which issued warrants for the establishment of Scottish Rite Lodges and Councils throughout the United States and Canada. All such Masonic bodies derived their authority either directly or indirectly from this original "Supreme Council," located in what is now the Masonic "Southern Jurisdiction" of the USA. Of the Eleven "brothers" meeting in Charleston in 1801 to found the "Supreme Council," nearly half were Sephardic Jews. Chief among these members of the Charleston Congregation Beth Elohim was Abraham Alexander, who served as its volunteer lay minister from 1785 to 1805. In those days ordained European rabbis did not live permanently in North America (where many Jewish emigrants had fallen away from strict Orthodox practices). Alexander, as the chief religious official at Beth Elohim, served as its spiritual leader, interpreted the religious law, performed marriages and funerals, and functioned much like an ordained rabbi. The other three Beth Elohim Jews who helped establish the Scottish Rite "Supreme Council" in Charleston were Israel De Lieben, Emanuel De La Motta, and Moses Clava Levy. Levy was a relative by marriage to the extensive Sephardic Seixas family of New York and South Carolina. Gershom Mendes Seixas, the patriarch of that family was the "hazzan" of the Congregation Shearith Israel in New York City. Seixas was functionally the first Jewish "rabbi" in America. Mordecai M. Noah's father, Manuel M. Noah, was a member of Congregation Beth Elohim during the Revolutionary War. He joined with the "Swamp Fox" General Marion to fight against the British, while "rabbi" Abraham Alexander was serving as a lieutenant of dragoons in Col. HillŐs regiment. After the war Manual M. Noah moved to Philadelphia and there, on July 19, 1785, his son Noah was born. The young Mordecai eventually moved back to the family's old home of Charleston, where he soon became involved in party politics and, no doubt, in local Masonic activities. During the War of 1812 Noah wrote patriotic articles for the local newspaper and soon gained enough national recognition to gain an appointment as the U.S. Consul to Tunis in 1813. It is likely that young Noah's appointment to this prestigious post came partly as a result of his family's connection with influential Jewish Masons in the Charleston Lodge. Mordecai M. Noah: Royal Arch Mason Given Noah's close ties prominent Scottish Rite Masons in the Congregation Beth Elohim at Charleston it may seem strange that he elected to follow the alternate path of "higher Masonry" offered by the friendly rival "York Rite" establishment. Mordecai was probably invited to become a Freemason shortly after his 21st birthday, and his induction into "the fraternity" was probably carried out in Philadelphia c. 1807-1810. It is safe to presume that he was indeed a Master Mason by the time he arrived in Charleston c. 1811. For some reason Mordecai either elected to join the York Rite after that, or, perhaps he was inducted into the Scottish Rite but later found the "Royal Arch" path of the Yorkers more to his liking. At any rate, Noah was probably a Royal Arch Mason by the time he delivered his famous speech of 1818, at the consecration of the Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue in New York. It may have been the Panic of 1819 and the economic depression in New York state which followed in its wake which convinced Major Noah to join his political allegiance with that of Martin Van Buren's Democratic "Bucktails" and against the equally Democratic "Clintonians." This same period saw the rise of New State legislator and Sate supreme court justice, Daniel D. Tompkins, (1774-1825). In 1807, while Mordecai M. Noah was presumably still living in Philadelphia, Tompkins was elected to the New York governorship. He was re-elected in 1810, 1813, and 1816. Tompkins became James Monroe's running mate and served with that notable statesman as his Vice President from 1817 to 1825. Clinton, on the other hand, lost his bid for national fame in the election of 1812 and afterwards contented himself with returning to his old job of being Mayor of New York City (1812-1815). In 1816 Clinton campaigned for the Governor's office, won, and served in that capacity between 1817 and 1828. Both Tompkins and Clinton were Major Noah's grand superiors in the higher degrees of Freemasonry. But, having attached himself to the rising star of Martin Van Buren, they were also Noah's political enemies. That fact must have put Major Noah in a sensitive position when he at last gave his support to Governor Clinton's "Ditch" -- the Erie Canal project. The Major Noah of 1825 supported Clinton's Canal, looked to the Governor as his supreme York Rite Masonic leader, and yet continued to be a rival "Bucktail" in the political arena. Perhaps Noah was just following the lead of his political mentor, Martin Van Buren, in giving his belated support for Clinton's project. If so, Major Noah had already come up with a way to turn that same canal project's successful outcome to his own advantage. He petitioned the State Legislature in 1820 to turn its freshly-acquired ownership of Grand Island (in the Niagara River near Buffalo) over to himself. It is doubtful that Noah would have gone to all the trouble of putting such a petition before the politicians in Albany if he did not have good reason to expect some kind of success. But the New York City Jew's partisan clout was insufficient to win the day in Albany and the bill sponsoring his request did not pass. Undaunted, Noah found other men of wealth who agreed to join with him in buying a good deal of the island from the State. That plan worked much better and Noah and his associates soon held title to most of Grand Island. All of these financial maneuverings were carried out during the give-and-take "log-rolling" of the gubernatorial campaign which put DeWitt Clinton back into the Governor's mansion in 1825. M. M. Noah's National Advocate, editorials of 1824 and 1825 mark him as a Van Burenite who had gradually come to champion some of Clinton's projects and policies, if not the man himself. The question remains as to whether or not Clinton in turn rendered any support for fellow-Mason Noah's 1825 Grand Island development scheme, his self-appointment as head of a restored Jewish government, and his demand for "three shekels in silver per annum" in taxes from every Jew in the world.  Royal Arch Masonic silver "temple tax" half-shekel Complexities of New York Freemasonry De Witt Clinton was elected June 6, 1816 as "High Priest" of the General Grand Chapter of Royal Arch Masons for United States of America; in other words, he was the highest officer of that Order. According to John I. Brooke's The Refiner's Fire The matter of who was "in charge" of the "brethren" in New York at the time Major Noah selected Grand Island for his great development project was made even further convoluted by the New York Masonic Schism of 1823. That little-known bit of Masonic history developed in parallel with Clinton's extension of his Erie Canal westward in the early 1820s. New York's western Masonic wing was then on the rise; new craft lodges were all the time being chartered, expanding their membership, and looking forward to great things when the Erie Canal was completed. At the same time, the established Masonic leaders in New York City and its satellite cities were a bit reluctant to delegate much of their fraternal power to these upstart western lodges. Quoting Brooke: The western lodges complained that they had no voice in the Grand Lodge affairs conducted in New York City, and they met in Canandiagua in 1821 to plan a restructuring of the governance of the Grand Lodge... [in 1823 Joseph Enos's] election as Grand Master precipitated the secession of the City lodges. Members of Enos's Canandiagua lodge, led by Nicholas G. Cheesborough, who was himself elected in the "Country" Grand Lodge in 1825, were directly implicated in the assassination of William Morgan... in 1826... Thus it was that several of the blue lodges in western New York State were in open revolt against the original Grand Lodge, headquartered in New York City. Brooke says that "of over 350 lodges on the Grand Lodge register in 1823, 27 lodges affiliated themselves with the City Grand Lodge and roughly 110 attended the Country Grand Lodge meeting in 1824, leaving over 200 lodges that sat out the controversy." Needless to say, most of the rebellious brethren who formed the schismatic "Country Lodge" were the residents of the cities and towns of western New York -- the same region into which "Clinton's Ditch" was steadily progressing and the same region where Mordecai M. Noah hoped to gather the Jews of the world after 1825. This fraternal imbroglio west of Syracuse probably meant that nobody was fully in charge of the Masonic situation out in the western lodges until well after the tragic fallout of the "William Morgan Affair." Brooke passes on the speculation that William Morgan of Batavia "in September 1826 was preparing to print the ritual secrets of the symbolic and Royal Arch Masons. Concerns that Morgan was going to expose corruption among the Country Grand Lodge leadership may well explain his death." As it turned out Morgan disappeared before any of his threatening revelations could see print in Batavia. The small book which was printed under Morgan's name after his disappearance focused only upon the "secrets" of the blue lodge rituals and said nothing of Royal Arch matters, nor of secret acts of darkness allegedly carried out by the Country Lodge leaders like Joseph Enos, S. Van Rensselaer, and John Brush. By 1829 the anti-Masonic ferver in the west had put the Country Lodge out of business and what remained of the state's craft lodges were reunited under Van Rensselaer  1825 Erie Canal Dedication: DeWitt Clinton Mingles the Waters LaFayette, the Erie Canal, and Grand Island -- all in 1825 The drama of the "William Morgan Affair" began about a year after western New York hosted visiting French General and Revolutionary War hero the Marquis de LaFayette in 1825. La Fayette arrived by lake packet in Buffalo on June 4th and received a hero's welcome. A couple of days later the Marquis was escorted to Lockport, where he entered the nearly-completed Erie Canal and began a leisurely trip to Rochester and points east. Newly re-elected Governor DeWitt Clinton arrived in Buffalo for the dedication of the Erie Canal four months later. The waterway dedication festivities were begun at Buffalo on Oct. 26, 1825 and were concluded in the City of New York two weeks later. The high-point of the lengthy celebration was the opening of the canal locks at Lockport in Niagara Co., where Clinton had the pleasure of seeing the eastern waters of his state mingle with those which flowed into the Great Lakes. Clinton and the great entourage progressed on in stages eastward until they reached Albany on Nov. 4th. Here "Alderman [Axelred] Cowdery made a handsome and pertinent address, in behalf of the Common Council, to which his Excellency made a reply in behalf of himself and his associates in the great work, and the several persons and bodies who had been welcomed to the shores and waters of New York..." (Narrative of the Festivities Observed in Honor of the Completion of the Grand Erie Canal, NYC 1825). The "Morgan Affair" also came well after Mordecai M. Noah gave his own dedication speech -- the one he had carefully written in support of his proposed "Israelite Gathering" on Grand Island in the Niagara River -- an stone's throw from Buffalo. Noah's celebration was something like a imitation of a great Masonic Erie Canal-builders bash DeWitt Clinton had staged in New York City two years before. Though a bit less elaborate than both Clinton's 1823 celebration and the extended party the Governor was soon to supervise in opening the Erie Canal, Noah's own Buffalo mimicry of Clinton's spectacles must still have been an occasion worthy of the limner's florid brush-strokes. Noah's dedicatory celebration took place at Buffalo in the lull between the departure of LaFayette and the arrival of Governor Clinton to begin the canal's opening festivities. No doubt many of the officials and dignitaries then gathering in the region to see LaFayette also intended to return for the beginning of Erie Canal dedication celebration at Buffalo. Quite likely many of those notables were already on hand when Major Noah collected his crowds on Sept. 15, 1825 and flamboyantly announced his "Revival of Jewish Government." A newspaper account published at that time recorded the progress of Noah's extravaganza: "the celebration took place this day in the village, which was both interesting and impressive. At dawn of day, a salute was fired in front of the Court House, and from the terrace facing the Lake. At 10 o'clock, the masonic and military companies assembled in front of the Lodge, and at 11 the line of procession was formed [including]... military, citizens, civil officers, state officers in uniforms, U. S. officers. president and trustees of the corporation, tyler, stewards, entered apprentices, fellow crafts, master masons, senior and junior deacons, secretary and treasurer, senior and junior wardens, masters of lodges, past masters, rev. clergy..." all congregated around the "Principal Architect -- Globe -- with square, level and plumb, -- Globe -- Bible, square and compass, borne by a master mason, the Judge of Israel in black, wearing the judicial robes of crimson silk, trimmed with ermine and a richly embossed golden medal suspended from the neck; a master mason, royal arch mason, knight templars..."Just as "rabbi" Abraham Alexander had worked closely with Freemason and Episcopal Rev. Fredrick Dalcho in Charleston in 1801, so also "Judge" Mordecai M. Noah gained the intimate cooperation of Freemason and Episcopal Rev. Mr. Searle of St. Paul's Church in Buffalo. Searle's choir sang "Before Jehovah's Awful Throne," previous the Reverend's sermon delivery. Searle also arranged for a "Psalm in Hebrew" to be sung before he pronounced his benediction upon the Jewish-Masonic-Christian assemblage. The 1825 newspaper article closes by saying, "on the conclusion of the ceremonies, the procession returned to the Lodge, and the masonic brethren and the military repaired to the Eagle Tavern and partook of refreshments." Major Noah obviously had St. Paul's rector, Addison Searle, "in his pocket" in 1825, but it is unlikely that Noah could have gained that useful cooperation out west without first having made friends with Dr. John Henry Hobart, the Episcopal Bishop of the Diocese of New York. Hobart was almost certainly an advanced degree Freemason. He was a very influential person in pre-Jacksonian New York State and in the City. With Hobart's at least nominal support for the Grand Island project in hand, Noah was able to orchestrate his ceremonies scheduled for Buffalo on September 15, 1825. He was assured far in advance of cooperative access to the town's Episcopalian church and its Masonic Lodge. Noah's plans called for more pomp and circumstance than what might be mustered up at the local Christian church, however. He also wished to put together an impressive procession complete with military bands and Masonic finery. Major Noah was able to bring together all of that for his spectacle on September 15th. But was the Masonic cooperation he received there rendered to him by the leadership of the "Country Lodge" or the "City Lodge?" Given Noah's obvious connections in New York City, and the fact that he had apparently never even visited Buffalo prior to 1825, it may seem safe to assume that he and his associates buttonholed leading NYC Masons like Bishop Hobart for the crafty benevolence later bestowed upon his Grand Island scheme. On the other hand, Noah's fellow-investors in the land development scheme included westerners from Penn-Yan, Geneva, and Buffalo. Noah's investment partner in Buffalo was Sherriff John G. Camp, a member of Rev. Searle's Episcopal congregation at St. Paul's and almost certainly a Freemason himself. Camp's name was not associated with the William Morgan abduction the next year -- so it is marginally possible that Camp and his fellow Masons in the Buffalo Lodge were either counted among the City Lodge members, or perhaps among those neutral brethren who supported neither side in the schism of 1823. The Disaster of 1826 Mordecai M. Noah's 1825 Grand Island project was killed by the William Morgan fiasco in Batavia and Canandaigua the following year. It is doubtful that Noah ever expected to gain world-wide acceptance of his new Jewish Government and his call to an American gathering. The European Jewish leaders were quick to discount him as a pious fraud and "a pseudo restorer." The best that the grand rabbi De Cologne could grant Major Noah was the "title of a visionary of good intentions." Assuming that Noah saw such a European response coming even before he composed his September 1825 Buffalo speeches, the probability remains that he still hoped to develop Grand Island, even without a great Jewish gathering there. To do that the New York City Jew needed allies and agents in the west like Sheriff Camp of Buffalo. The less accommodating and less wealthy Yankee Calvinists who made up the bulk of western New York's population were much less supportive of non-Christian, big-city sharpsters who had come to their neck of the woods to survey and sell city lots in unbuilt utopias. And, in fact, the anti-Masonic hysteria which followed the "Morgan Affair" demonstrated that fact quite well. By the middle of 1827 practically every Masonic lodge west of Syracuse had ceased to function and the brethren were bailing out of the fraternity by the wagon-load. Calvinist ministers in the "Burned-over District" pressured their members to renounce Freemasonry or leave the fold. Leading citizens who had previously held State and local office either joined the anti-Masonic ranks or quietly moved to a region of the country where the lodges still operated openly without much opposition. Even towns such as affluent, Episcopal Canadiagua became a center for anti-Masonic muck-raking and mud-slinging, with the establishment of "anti" newspapers like W. W. Phelps' Ontario Phoenix. The same popular outrage and self-righteousness piety which cast out Masonic judges, sheriffs, and the occasional apron-bedecked minister also gave energy to the founding of new political alliances and unusual religious practices (such as Mormonism). Perhaps many of the "anti-Mormons" of the late 1820s and early 1830s in western New York were really "City Lodge" brethren venting their frustration on the alleged excesses of the apostate "Country Lodge" leadership. In time many of those same New York anti-Masons drifted back into their comfortable old seats in new or re-established lodges, either in the Empire State or out on the western frontier in such unlikely craft communities as Elkhorn, Wisconsin or Council Bluffs, Iowa. Mordecai M. Noah road out the storm in the safety of Gotham's urban high-rises, eventually disposing of his Grand Island property and giving up the idea of an American Zion altogether. Still, one cannot help but wonder what might have happened, had the grand rabbi De Cologne smiled upon Noah's project and had William Morgan never tried to expose the secrets of Freemasonry in the Burned-over District. INTRODUCTION |

Return to Top of This Page

Return to: Spalding Research Project (Introduction)