unOFFICIAL JOSEPH SMITH HOME PAGE

The TREASURE SEEKERS

Joseph Smith: (Illustrations & Photos) | (Maps & Images) | (NY Histories) | (Money Digging)

"Philosopher" (1792) |

News Items (1820-60) |

D. Thompson (1836) |

G. H. Harris (1887) |

D. Dengler (1946) |

G. Hurley (1951) |

W. D. Hand (1980) |

A. Taylor (1986) |

Mounds Mystery | Captain Kidd | American Israelites | Rods & Stones | Gold Diggers

1-5 | 6-10 | 11-15 | 16-20 | 21-25 | 26-32 | map | notes

~+~+~+~+~+~+~+~+~+~+~+~+~

[ ii ]

[ iii ]

[ iv ]

[ v ]

I am convinced, that it is impossible for one person to please all mankind, for there is such a variety of opinions predominent, that no one system or pamphlet will meet with universal approbation; but it appears to me requsite, that something of this kind should appear in public -- and, as I have been solicited by numbers, to attempt a brief narration, with particulars, relating facts concerning many occurences that happened in the county of Morris, and state of New Jersey, in the year 1788. -- As I am convinced that many erroneous ideas have been propogated, therefore the generality of people are destitute of real facts -- I am sensible that it is natural for men to censure each other with burlesque, and say, they had not sagacity adequate to discover the plot; but after an intrigue is discovered, every person that had not an active part in it, thinks his own sagacity would have been sufficient to discover the deception -- but this we know, that only few men are ever satisfied, and when any curiosities are presented to them, they are zealous in the pursuit of knowledge, and anxious to know their terminations, and many will anticipate great gain, and contribute liberally until the fraud is detected; I shall therefore be as brief as possble, as it is my intention to eradicate many capricious notions from the minds of many who have imbibed witchcraft and the phenomena of hobgoblins. * __________ * It is evident, that legerdemain has been very conspicuous and prevalent even from the earliest periods of time, and many have been imposed upon by these deceivers; and credulous honest people have had ideas imbibed to that degree, concerning' witchcraft and legerdemain, that they were deaf to philosophy -- and reasoning was insufficient to eradicate those notions, until they were taught by the school-master of experince; and then, the compensation they received was to regret the loss of their time and interest. [ vi ] It is well known that many impositions have been inflicted upon mankind, by particular persons in every country; and in the earliest periods of time, many remarkable occurrences took place, that much surprised the greater part of mankind, induced them to believe that such wonderful phenomena could not take place, only by a supernatural power. Every person that is acquainted with human nature. or has studied the disposition of mankind, must be fully convinced of the deception of man, and certainly know, there are persons, whose abilities, disposition and genius, are in every respect, adequate to the profession of deceivers. And many of their co-temporaries confide in their abilities, integrity and veracity, to that degree, that they will sacrifice their property, through ignorance, to support a vicious, ignoble, defrauder. Nor is this much to be wondered at, if we contemplate the avaricious disposition of men, who are ever in search of objects in futurity, especially such as have a tendency to produce gain, they will pursue with the greatest alacrity, anticipating joys which, upon a near approach, elude the grasp. It is obvious, that some illiterate persons have a genius adequate to prepossess themselves in favor with many, and by an enegmatical behaviour, induce some to form eminent opinions of their merit, at the same time it was paradoxical. And If we suppose that every generation grows wiser, we must believe that ignorance has been gradually extinguishing for some hundred years past; and it is almost Incredible to believe that any impositions could be practised upon mankind at this enlightened period; but although knowledge is more diffuse, human nature is still the same, and Judas like, will perpetrate enormous deeds to satisfy an avaricious mind. And if we admit the same disposition to reign predominant, in the deceived, as the deceiver then let the deceived pay their money to the deceiver, who has been at trouble and cost in obtaining his art of extracting, for those who go to the school of experience may expect to pay dear for their tuition.

[ 7 ]

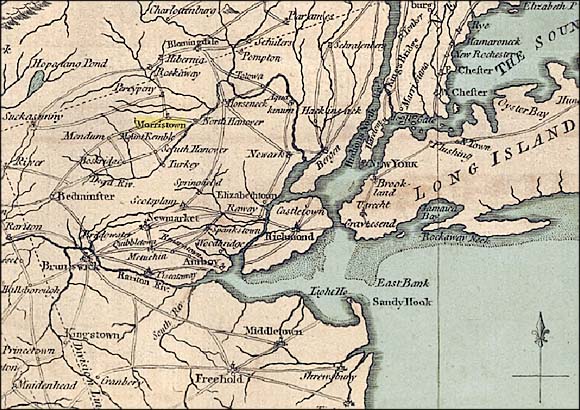

A diabolical intrigue invaded the county of Morris, in the state of New Jersey, in the year 1788. This unequalled performance, has taken vent and is promulgated throughout the continent, and deserves the attention of every person. But before I proceed any further, I think it requisite to advert a few minutes to the general character of that place. It is very conspicuous that many of the people in that county, are much attached to machinations, and will spend much time in investigating curiosities. I don't say whether such a turn of mind is to be imputed to indigence or owing to the operation of the climate: this I submit to the candor of every person to determine within himself -- it is obvious to all who are acquainted with the county of Morris, that the phenomena and capricious notions of witchcraft, has engaged the attention of many of its inhabitants for a number of years, and the existence of witches is adopted by the generality of the people. I was once in Morristown, and happened to be in conversation with some gentlemen, who had, as it were, the faith of assurance in witchcraft. They informed me that there were several young women who were bewitched; and they had been harrased so much by witches for a long time, and all their experiments proved abortive, and the young women were so much debilitated they were fearful they would never recover ( 8 ) their healths. They related several occurrences, that I think too simple to mention; but one instance was, "that an old lady was churning, and being much fatigued, and unable to obtain butter, she at last concluded that the witches were in the churn, and immediately had recourse to experiments, which were, that of heating several horse-shoes, and putting them into the churn alternately -- she burnt the devil out and immediately obtained butter." I perceived that the generality were apprehensive of witches riding them, and the greatest evidence of a witch was, if a woman had any deformity, or had lived to that age to cause wrinkles in her face, she had the appellation of a witch. There was another occurrence that happened on Sunday. They informed me a man was driving his sheep from his grain, and an accident happened as they were jumping over a fence, one of the sheep broke its leg. The man for some time before supposed that the same sheep was bewitched. About the same time, an aged old lady returning from church, her horse unfortunately stumbled, she fell to the ground and broke her leg -- This was received as an indication that she was a witch: And in fact, if a horse had the belly-ache, or any beast was in agony of pain and behaved uncommon, the general opinion was, that the creature was bewitched. It is my opinion, that persons actuated by such capricious notions, are predisposed for the reception of marvelous curiosities whenever they occur. I shall now proceed to detail as near as possible, relative to the transactions of that phenomena, Legerdemain, and Hobgoblins that happened in Morristown in the year 1788. This transaction has occupied the attention of many & caused great wondering through the state, and every ( 9 ) person is eager to acquire a thorough knowledge of the real transactions; and I hope this will have a tendency to eradicate such capricious notions from every rational mind. -- The chief conductor of this deception, was Ransford Rogers, a native of Connecticut, in New England. He was an illiterate person, but very affable. possessed of a genius adequate to prepossess himself into favor with many, and great facility to display his abilities with the greatest brilliancy. He resided in the state of Massachusetts for a number of years, and from thence to the state of New York. His place of residence, before he came to New Jersey, was Smith's Clove, where he taught a school. During his residence at Smith's Clove, two gentlemen from the county of Morris, who had been long in search and digging of mines, but had always proved unsuccessful for the want of a person whose knowledge descended into the bowels of the earth, and could reveal the secret things od darkness . There was also a prevailing opinion, that there was money deposited in the bowels of the earth, at Schooter's mountain, with [an] enchantment upon it. - that it could not be obtained without a peculiar art in legerdemain, or to dispel the hobgoblins & apparitions. These gentlemen, in pursuit of a man that could work miracles, accidentally found Rogers, and after a short conversation, made known their business to him, and concluded that he was the man every way calculated to their wishes, for he was very fond of giving hints of his extensive knowledge in every art and science, but careful not to go so far as to demonstrate his propositions. He had a pretended copious knowledge in chemistry; and could raise or dispel good or evil spirits. He then agreed with those gentlemen to supply them with whatever was requested -- This was a noble man indeed! Now ( 10 ) they concluded that the man was found who could supply them with all things; and one who was endowed with power and sagacity not to be exceeded by finite wisdom. But altho' Rogers had engaged to exhibit miracles, knowing that he must seek inventions, he thinking it too great an undertaking, began to regret, fearing that he was not able to perform: but after he had undertaken, and given hints of his knowledge and abilities. and being solicited by the gentlemen to proceed, he could not elude what he had advanced, but resolved to have recourse to experiments and stratagem to prove his assertions. He was then solicited to remove to Morristown. Those gentlemen, with indefatigable pains, procured him a school, three miles from Morristown. This was satisfactory to Rogers being confident of their integrity, and perceiving their flexibility and readiness to administer to his relief, he thinking himself happy with such noble concomitants left Smith's Clove, with the greatest alacrity, and took his abode about three miles from Morristown, where he presided over a common English school. This was a place every way suitable for a man of his profession, for they were predisposed for his reception, fond of marvellous exhibitions, which he was able to facilitate with the greatest alacrity -- this was in August 1788. While he presided over the school, he gave satisfaction to his employers, and manifest proofs of his integrity. By this time he had possessed himself in favor with many but it is likely they expected reward. Sometime in September, as he had been importuned to exhibit his art in raising and dispelling apparitions, and prove his abilities as he had asserted. He then finding himself deficient, and perceiving it requisite to have an assistant in order to carry on nocturnal performances, ( 11 ) with the greatest secrecy. He then obtained leave of his employers, to absent himself a few days and return to New-England for his family and some other business upon his promise to return as soon as possible. While he was in New-England, he contracted with a person, a schoolmaster, to return with him, insuring him a school that would be very lucrative. -- Rogers. agreeable to his promise, was as brief as possible, and returned with his new companion to Morristown, where he was saluted by persons of eminence and congratulated by many after his long absence. This was in September 1788. Rogers now being furnished with an assistant, he is able to facilitate nocturnal performances with the greatest dispatch. As it was now the Iast of September, many soliciting Rogers to exhibit his art in raising and expelling apparitions, as he had engaged. The first object that is to be now attended to is, to obtain a supposed hidden treasure, that lies dormant in the earth at Schooler's Mountain. This capricious notion had been of long standing, and was then a predominant opinion, among the greater part of Morristown, as they said there had been repeated efforts made to obtain the treasure, but all had proved abortive; for whenever they attempted to break the ground, there would many hob goblins and apparitions appear, which in a short time, obliged them to evacuate the place. [It is well known, that persons being apprehensive of feeing apparitions, their imagination causes them to arise; but they always imputed their disappointments, to the mismanagement of their conductor, as not having sufficient knowledge to dispel those apparitions, that impeded them from obtaining the treasure.] ( 12 ) Rogers, after gathering information from every quarter, and hearing the obstructions that debarred them from obtaining immense riches, was now satisfied this was the time for him to fulfil his former assertions. He then secured the veil of ignorance upon their heads, with an intention to extract money from their pockets; therefore after deliberation, he thought it necessary to convene a number of gentlemen at a certain place in order to consult what method must be taken to obtain the above mentioned treasure. This meeting was the greatest secrecy, & their number about eight Here Rogers communicated to them the solemnity of the business and the intricacy of the undertaking informing them there was an immense sum deposited at the above mentioned place; and there had been several persons murdered and buried with the money, in order to retain it in the earth. He likewise informed them, that those spirits must be raised and conversed with, before the money could be obtained. He likewise declared, that he could by his art and power, raise them apparitions, and the whole company might hear him converse with them, and satisfy themselves that there was no deception. This was received with belief and admiration by the whole company, without ever investigating whether it was probable or possible. -- This meeting therefore, terminated with great assurance, they all being confident of the abilities, knowledge and power of Rogers. By this time it appeared to those gentlemen, that the hidden treasures of darkness which had so long lay dormant in the earth, was to be obtained by the power of this mighty man! Rogers informed them, that he should have interviews with the spirits; and as the apparitions knew ( 13 ) all things, they must be careful to walk circumspectly, and refrain from all immorality, or they would stimulate the spirits to withhold from them the treasures. These gentlemen now under apprehensions of great riches, began to propagate their intentions to particular friends, and there was such a prospect of being rich that many were anxious to become members; and additions were added unto it daily, of such as expected great riches. The company convened almost every evening until their number increased to about forty. During this time, none had interviews with the spirits except Rogers, and he communicated their conversation to the society, which was admitted as real facts. Now you will observe, that it is highly necessary, that Rogers would have associates, in order to facilitate his manoeuvres and avoid detection. During his time Rogers and his connections had recourse to several experiments in compounding various substances, that being thrown into the air would break with such appearances as to indicate to the beholders to rise from a supernatural power. He had compositions of various kinds: Some by being buried in the earth for so many hours, would break and cause a great explosion, which appeared dismal in the night and would cause great timidity. The company were all anxious to proceed and much elevated with such uncommon curiosities. A night was appointed for the whole company to convene and it happened to be a most severe stormy night, but every man was punctual in his attendance. Some rode eight some twelve miles, when the inclemency of the weather was sufficient to extinguish health. At this interview they were all much astonished with an unexpected interview with the spirit, who related unto them the importance of their regular ( 14 ) proceedings, or they could not obtain their desire. The spirits informed them, that they must meet on such a night, at a certain place, about half a mile from any house in a field, retired from travelling and noise, and they must form certain angles and circles and they must proceed in drawing their lines and forming their circles as Rogers directed, and then be careful to keep within the circles, or they would provoke the spirits to that degree, they would finally extirpate them from the place. The night appointed for them to convene, being now arrived, they all with joy, fear and trembling, convened at the appointed house, about half a mile from the field. This field was environed on the north and west by a thick wood. The circles and angles being drawn the preceding day, they all proceeded from the house about ten o'clock in the evening, with peculiar silence and decorum, and entered the circles with the greatest solemnity, and being fully sensible they were surrounded by apparitions and hobgoblins, Upon one point of the circle was erected four posts in order to spread a cloth, and form a tent where Rogers could preside, as governor of the ghastly procession. The number that entered these circles were about forty. This number was walking alternately during the whole procession. It is not to be wondered at, if people were timorous in this place, for the candles illuming one part of the circle, caused a ghastly, melancholy, direful gloom, towards the woods, for it was a dark night. Every person must suppose that this is a suitable place for the pretended ghosts to make their appearance and establish their faith in hobgoblins, apparitions, witchcraft and the devil. After they had been rotating within the circles for ( 15 ) a considerable time with great decorum, they were instantaneously, shocked with the most impetuous explosion from the earth at a small distance from them. -- This substance was previously compounded & secreted in that place a few hours before. The flames rising at a considerable height, illuminated the circumambient atmosphere, and presented many dreadful objects, from the supposed haunted grove, which was instantaneously involved in obscurity. Immediately after the pretended ghosts made their appearance, with a hideous groan, They remained invisible to the company, but conversed with Rogers, in the hearing of the company -- this was in Nov, 1788. The spirits informed them, that they had possessions of vast treasure, and could not give them up unless they proceed regular, and without variance; and as fortune had discriminated them to receive the treasure, they must deliver to the spirits, every man, twelve pounds, for the money could not be given up by the spirits until that sum was given to them. They must also acknowledge Rogers as their conductor, and adhere to his precepts, & as they knew all things, they would detect the man that attempted to defraud his neighbor. These pretended ghosts had a machine over their mouths, that can fed such a variation in their voices, that they were not discovered by any of the company during the procession; which lasted until about three o'clock in the morning. Now the whole company confide in Rogers and look to him for protection to defend them from the raging spirits; and after several ceremonies Rogers dispelled the apparitions, and they all returned from the field wondering at the miraculous things that happened, being fully persuaded of the existence of hobgoblins and apparitions. -- By this time they could revere ( 16 ) Rogers, and thought him something more than man. Thus far, every project terminated agreeable to his wishes; and he had such influence over them, with a despotic power, that it is my opinion, had he put one of them to death, he would have been justified and defended by the rest. After this conference was over, and all agreed to deliver the apparitions twelve pounds, as soon as possible. Rogers, perceiving that every man was not under circumstances to give twelve pounds, his generosity therefore induced him to reduce the sum to six pounds, and those who were not able to produce that to give four pounds. Rogers to confirm them in the faith, pretended to have nocturnal interviews with the spirits, and communicated to the society, therefore, they convened some of them almost every night, and as fast as they could get the money, they would convene and deliver it to the spirits; and whenever they met in a secret room, the door and window shutters being made fast, and Rogers communicating his interviews to the company, Unusual noises would be heard about the house, that would cause great timidity. Groanings and wrapping upon the house, the falling of boards in the chamber the gingling of money at the window, and a voice speaking, "Press forward!" The superficial machine that was over the mouth of him who spoke, so much altered his voice, that no one could detect him. The spirits declared that they were sent to deliver that society great riches, and they could have no rest until they had given it up; but the money they requested, was only an acknowledgement for such immense treasures. Methinks I hear every man anticipating future greatness, but I expect time will defeat the enterprise. ( 17 ) There was now a sort of emulation among them, who should first deliver the money to the spirits, but some of them was weak in faith, which caused animosities and disputes among them; and meetings were called almost every night during the winter. The reader will observe one circumstance in particular, that occasioned the business to continue through the winter, which was, the money that the spirits requested, must be silver or gold, and the current money then in Jersey, was loan paper: This money did not circulate only in that state, and no person would take it in lieu of silver and gold, only at one quarter discount. This therefore had a tendency to continue the business thro' the winter, as it was almost impossible for some of them to get silver or gold; but all of them were very industrious seeking the sum required. They would give almost any discount or interest that any man pleased to ask. They would mortgage their farms and dispose of their cattle at half price, rather than fail in obtaining the required sum. It is very obvious why Rogers and his associates, the supposed spirits, requested silver or gold, for they wanted to carry it out of the state, and paper money would have been of but little service. Sometime in March, the money being chiefly deposited in the hands of the spirits. Rogers fearing that something might happen, pretended to have nocturnal interviews with the spirit, likewise several persons, especially those who had the most faith and men of veracity were called out of their beds in the night by the spirits, and directed how to proceed. These gentlemen immediately made known to the company their interviews with the spirits and when the company were convened into a private room, the pretended spirits were outside of the house, groaning, ( 18 ) gingling of money, telling them to have faith, be of good cheer, and keep secret all transactions, and in May next they should receive the treasure. -- This was in March 1789. They all returned with joy, fear and wondering, being very liberal, waiting impatiently for May to come. Now Rogers and his associates have received the greater part of the money, and they are full of machinations, how shall postpone the business the next meeting, for all expected to proceed to Schooler's, Mountain the next May, and receive the treasure. The night appointed being now arrived, they all convened in a large circle in an open field, waiting for the ghosts to appear and give them farther directions and proceed with them to the place where the money was deposited. Immediately the ghosts appeared without the circle, with great choler, and hedious groanings, wreathing themselves in various positions, that appeared most ghastly in the night -- then upbraiding the company declaring they had not proceeded regular, and some of them was faithless, and had divulged many things that ought to have been kept secret: and by their wicked dispositions and animosities that had taken place among them, debarred them at present, from obtaining the treasure. The pretended ghosts, raging to that degree at the misconduct of the company, that Rogers, who appeared or pretended to be very much frightened with the rest, with all his art and pleading was scarcely able to pacify the raging ghosts. At this the company confiding in Rogers, looked to him for protection. The ghosts informed them, they must wait patiently, until some future period. They were now so much timidated, that they thought but little about money; at length Rogers, after a variety ( 18 ) of ceremonies by his art and power, dispelled the frightful apparitions, and tranquility, once more, resides within the circle. They now returned from the circle, still retaining their belief, revering and adhering to Rogers in all things. Thus far they have been seduced. They gave their money to Rogers and his associates, instead of apparitions, and are waiting for the spirit to return and lead them to anticipated fortunes. Had Rogers now halted, and not proceeded upon another project, he would have been feared and respected; & the capricious notions of witchcraft, hobgoblins, and the devil would have prevailed among them, with prejudice, fear and ignorance, until this day, But this diabolical intrigue and the succeeding one, has diffused light, and eradicated ignorance from the minds of many. This scene ended the first of May, 1789. It is evident that Rogers did not intend to proceed any farther upon such diabolical intrigues; but some time in the fall preceding the termination of the first scene, two young men from New England, took up their abode in the county of Morris; Some time[in] the fore part of the winter, one of them took up his abode in Morris. Rogers at that time taught a school three miles out of town, but soon quitting his school there removed to Morristown. These young men soon became very intimate with Rogers, which was the cause of another diabolical intrigue, although their behavior was circumspect -- Sometime in April these young men left Morristown, and removed about twenty miles, but still continuing a correspondence with Rogers, by letters and frequent visits. Although these two men were removed at the distance of twenty miles from Rogers, it was a favorable ( 20 ) opportunity for them to gain prosylites: as it is evident they seduced many, and some of eminent characters, that would have joined the company and proceeded in anticipating great riches, but Rogers thought it not proper to admit them, as appeared from the corresponding letters with Rogers and the fire club. I before mentioned, that the business of the former company terminated the first of May, and as Rogers and his former associates have succeeded so well, in extracting money with new inventions, that Rogers again undertakes, with great alacrity upon a new project. A company now convene, that consists only of five. They proceed upon various manoeuvres, rotating the room in order to raise the spirits, while they were performing many ceremonies, various noises were heard around the house: The rattling of a wagon -- groaning, -- striking upon the windows, &c. Then each one taking a sheet of paper, extending his arm, holding the paper out at the door, waiting for the spirit to write upon one of the papers, how they should proceed! After waiting some time, each on folding his paper, proceeding regular around a table then opening their papers on one of them was writing; directing them to Convene upon such [a] night, and the spirit would give further direction how they must proceed. Previous to this Rogers had prepared the writing, but wanted more time for consideration; therefore they were dismissed with orders to convene on such a night. The night arrived -- they convened at Rogers house in order to receive information from the spirit that Rogers and one of the associates pretended the had interviews with. ( 21 ) After they had all convened, the first manoeuvre was, both the deceiver and the deceived unite in prayer upon their bended knees; then parading according to their age proceed rotating the room, as many times as there were persons in number; then parading round a table, each one drawing a sheet of paper from a quire and Rogers folding them, delivered to each man one; then they proceeding, in order, a small distance from the house, and drawing a circle, about twelve feet diameter, they all stepped within it, unfolding their papers, extending them with one arm, fell with their faces to the earth, continuing in prayer with their eyes closed, that the spirits might enter within the circle, and write their directions upon the papers; then Rogers giving the word "Amen!" prayer ended, and each one folded his paper -- rose, and marched into the house; then unfolding their papers, the writing appeared upon one of them, to the great astonishment of most of the company. This writing was to be kept safe in the hands of one of the associates, to exhibit when occasion called in order to gain prosylites, relating to the misteries of the paper. The contents of the paper was, that the company must be increased to eleven members, and each one must deposit to the spirit the sum of twelve pounds, silver or gold. This writing Rogers and his associates prepared previous to this time, therefore the meeting was dismissed, and each one exerted his influence to gain prosylites. Rogers and his associates now finding the minds of many flexible, resolved to proceed upon some new project, that might have a tendency to prove more lucrative. Rogers therefore, wrapping himself up in a sheet, went to the house of a certain gentleman in ( 22 ) the night and called him up, by wrapping at the door and windows, and conversed with him in such disguise that the gentleman thought he was a spirit. The pretended spirit relating to him, that he had vast treasures in his possession, and a company was in pursuit of it, and he could not give it up unless some of the members of the church joined them, such as I shall mention: for said he, I am the spirit of a just man, and am first to give you information how to proceed, and put the conducting of it into your hands; and I will be ever with you and give you directions when you go amiss; therefore fear not, but go to Rogers and inform him of your interview with me. Fear not, I am ever with you! This gentleman, not apprehending any deception, believed it to be a spirit. Early in the morning he went to see Rogers, and found everything that the spirit related to be fact; he therefore was convinced, that it was from a supernatural power. He then went to inform those members belonging to the church, as the spirit had directed him. He found them very flexible -- giving great heed to his declaration, and anxious to see curiosities. But whether these church members were induced by self motives, or by a zeal to help their fellow creatures I do not say; but the plan that Rogers and his associates had in view, is very obvious, for this could not be obtained only under a cloak of religion. After this none were admitted to join the company only those of a truly moral character, either belonging to the church or abstaining from profane company, all walking circumspectly. This was in June, 1789. The company now increased daily of aged, abstemious, honest, judicious, simple church members. -- It is now in a religious line; and Rogers having put it ( 23 ) into the hands of another to conduct, he and his associates were busy every night, in disguise, appearing to particular persons, especially those who were most weak in faith, calling them up in the night, and ordering them to pray without ceasing, for they were just spirits sent unto them to inform them, that they would have great possessions if they would persevere in faith. Rogers and his associates, under the title of spirits, had ordered the conductor, that the company must consist of thirty-seven members; and every member must deposit into the hands of the spirit, twelve pounds silver or gold. -- The company now convened, about twenty in number, the spirit had ordered the conductor to proceed in certain maneouvres, in order to obtain directions from the spirit, that would be satisfactory to every member, for some were deficient in faith. Rogers and some of the associates always convened with the rest, wondering at such marvelous things. -- This was policy that they might not be suspected. While they were sitting in the room, several noises were heard around the house; groaning, wrapping at the windows, gingling of money, &c. The spirit then spoke these words, "LOOK TO GOD!" They all were amazed at such things, and Rogers with the rest wondered! They fell upon their knees to pray; and after this ceremony was past, all arose and walked alternately around the room, five times; then parading around a table, and each man drawing a sheet of paper from a quire, it was folded up, and all hustled together, and each man taking one, and tying a white handkerchief round his head and loins, they all marched with great decorum into a meadow about one hundred yards from the house. Previous to this, ( 24 ) Rogers having prepared a writing, and when going to the meadow, he put the blank paper into his pocket, and took the writing out, unnoticed by any of the company. After they arrived in the meadow at the appointed place, they rotated a circle five times, about thirty feet diameter, -- then they all stepped within the circle, and unfolding their papers, they all fell with their faces to the earth, with one arm extended, holding the paper, that the spirit might enter within the circle and write upon one of their papers, how they must proceed. They were ordered not to look up upon their perils, but to continue fervent in prayer In about ten minutes the commander gave the word "Amen!" They all rose, and folding their papers, they were hustled together; then each man drawing one, they marched alternately from the place into the house, with great decorum, they all parading around a large table, the next thing was to see if the spirit had given them any directions how to proceed; then each one unfolding his paper, the writing exhibited plain on one of their papers in a most curious manner. This writing was so elegant, that they were much astonished, thinking it a miracle, or supposing that the spirit entered the circle and wrote the contents, while they were on their faces at prayer. The contents of the writing was, O faithful man! What more need I exhibit unto you! I am the spirit of a just man, sent from Heaven to declare these things unto you; and I can have no rest until I have delivered great possessions into your hands; but look to GOD, there is greater treasure in Heaven for you! O faithless men! Press onward in faith, and the prize is yours! It also mentioned various chapters in the Bible, that the members must peruse, and particular psalms for them to sing; and the company must consist of thirty-seven ( 25 ) members; and each man must deposit into the hands of the spirit according to his circumstances, not exceeding twelve, nor less than six pounds; and the money must be given up as soon as possible, in order to relieve the spirit from his exigencies, that he might return from whence he came. Rogers and two of his associates were present and appeared to be astonished with the rest, but were not suspected by any of the company. They all agreed, that as fast as any of them could get the money, it should be given to the spirit; but they must meet at such a place, and give it up in a legal manner. A few days after this about twelve members convened, but only seven had the money ready to appropriate unto the spirit. The manner of their proceeding was, they convened in a room, and after several ceremonies and prayer being ended, they arose, & rotated the room, alternately, several times; then went with the greatest decorum, into a meadow, about one hundred yards from the house and drawing a circle about twenty feet diameter, they stepped within it, waiting for the spirit to make its appearance. After a short time, the spirit whistling, at the distance of about sixty yards from the circle, the commander then left the company and went to converse with the spirit; he soon returned with orders from the spirit, that all those who had the money, should retire to a certain tree, about forty yards from the circle. Now those who had the money went with the commander to the tree. The spirit appeared about twenty yards distant from the tree, with a sheet round him, jumping and stamping repeating these words, "Look to GOD!" Those that stood by the tree made a short complicated prayer, and laying the ( 26 ) money at the root of the tree for the spirit to receive they retired to the company. They all returned to the house, observing the greatest order, trembling at every noise and gazing in every direction; supposing they were surrounded by hobgoblins, apparitions, witches and the devil. Rogers and two of his associates pretended to give up the money which was only blank paper. This pretended spirit was one of the associates with a white sheet around him, and a machine over his mouth that his voice might not be detected by any that knew him; and immediately after the spirit had deposited his money, this spirit takes it to himself which was about forty pounds. Previous to this Rogers pulverized some bones and had given it to the commander, declaring that it was the dust of their bodies, and each man must have some of this powder in a paper sealed, as a token of the spirits approbation, & that he was one of the company. This powder was to be kept secret, and no one to touch it upon his peril. A sufficient quantity of liquor was also prepared, which the spirit had ordered to be used very freely; then each one taking a hearty dram, they all united in fervent prayer, after which the meeting was concluded. It is very obvious that spirituous liquors when taken in large quantities, will augment the ideas of men and induce them to anticipate profit and pleasure, although they are inaccessible in futurity. -- Some of the members caused great disturbance, by their diving, inadvertently, to excess in that powerful stimulus, but it is something pleasing to see aged, sober abstemious men with their ideas raised, put on cheerfulness and vivacity. Thus they proceeded as above mentioned, in giving ( 27 ) their money to the spirit every few evenings. The spirits brought to the commander several curiosities. that were to be exhibited to the company in order to confirm their faith, but were to be delivered to the spirits whenever they call for them. Various ceremonies were performed that I shall omit as they are too simple to mention, but every means were taken in order to make the members use liquor freely, the spirit gave unto the commander a compounded mars that was to be made into pills, and each one to take a pill at every meeting, and except he used very freely of liquor it would operate in making his mouth and lips swell; Thus they caused some to drink to excess, through fear, although they before observed the greatest temperance, and in fact some drank to that degree, to obviate the effects of the pill, that they were almost incapable of navigating in the night. Thus the company had increased to about thirty-seven in number; and the greater part had given the money to the spirits and circumstances prevented or delayed the rest from doing it, although every one was as brief as possible and spared no pains to procure the money. The company were now all engaged being much augmented with the prospect of being rich and soon expected to reap the harvest with pleasure, and receive their anticipated gain; but an accident now occurs, that terminates in the discovery of the plot, which is this: One of the aged members that had one of these papers, supposed to contain some of the dust of the body of the spirits, as I before mentioned, was to be kept secret and no one to touch it. This man leaving it accidently in his pocket in the house, his wife happened to find it, broke it open and perceiving ( 28 ) the contents, feared to touch it supposing it to be witchcraft: She went immediately to the priest for advice -- He, not knowing its composition was unwilling to touch it for fear it might have some operation upon him. When her husband discovered what she had done, he was much terrified, declaring that she had ruined him forever, in breaking open that paper. This made her more solicitous to know the contents; and she declaring not to divulge anything, he told her the whole of their proceedings; she insisted on it, they were serving the devil, and thought it her duty to put an end to such proceedings. This made great disturbance in the company, and Rogers and his associates were in disguise every night, appearing to particular persons as spirits, in order to confirm them in the faith and prevent a discovery. -- At last one evening Rogers having drank too much of the good creature, taking a sheet with him rode to a house of a certain gentleman in order to converse with him as a spirit; but making many blunders the woman thought it was a man, but after conversing with him some time, and going to prayer, Rogers departed declaring that he was the spirit of a just man. In the morning as soon as it was light, the man went out where the spirit appeared, and as there had been a heavy dew that night, he perceived the tracks of a man, and following him to the fence where he perceived a horse had been tied; he then tracking the horse to the door where Rogers lived. -- But as Rogers was not within, he followed the same track to the house of a certain gentleman, about half a mile distant, where he found Rogers; and as the gentleman of the house had, the evening before, lent Rogers a horse, together with many other circumstances ( 29 ) sufficient to convict him. The authority was then consulted, and judging him culpable, he was immediately apprehended and committed to prison. This detection greatly alarmed the whole company as they were unwilling to believe that Rogers was the spirit, even when the clearest evidence demonstrated that he must have been the ghost in question -- but Rogers declaring his innocence, was in a few days bailed out, by a gentleman that I shall call by the name of Compassion, and to this gentleman Rogers ought to ever pay a debt of gratitude and benevolence. After Rogers was clear of the jail, he perceived he was among his enemies, he therefore made his flight. but being pursued and apprehended the second time, he confessed his faults, and owned that for his conduct and the expressions he had used in his projects, he deserved punishment; but fortune favored him, and he once more eluded their hands. Now many threatenings and horrid imprecations proceeded from many after this man, who only a few days before, they revered and thought him a superior being. The cause of these imprecations being cast after him is very obvious, that is while he continued with them in parables, working miracles, he promised them great riches, but now he is gone, their hopes are all eradicated, But ought not the county of Morris to perpetuate and honor the name of Rogers for eradicating ignorance and causing the light of reason to illume the minds of many, where obscurity had reigned for many years? There have been various reports propagated concerning the sum that Rogers and his associates obtained from the believers of witchcraft, but the whole ( 30 ) amount was about five hundred pounds. But after Rogers had taken the veil from their eyes, and extracted money from their pockets, they were unwilling that he should have any compensation, but insisted that he should be brought to condign punishment, therefore Rogers is detected in his knavery, and his associates are unknown to the world; but had Rogers persevered, and avoided detection until all had given in their money, he would have left them in ignorance, waiting with patience for the return of the spirit, as was the case with the former company; but his being detected, and confession demonstrated to every person that there was neither witchcraft nor blackart in any of his performances, which they thought to proceed from supernatural power. I am confident that this occurrence is sufficient to extirpate all capricious notions of witchcraft, wizards, hobgoblins, apparitions and frightful imagination from the minds of rational beings. I am confident that there are many such kinds of impositions transacted by particular persons, and many illiterate and vulgar readily believe that they have power sufficient to call into being the souls of those dead bodies that have long slept dormant in the earth: But let reason be our guide, and we shall soon exclaim against such capricious declarations -- But one half of the world will not investigate whether these things are either probable or possible, but proceed with alacrity upon the affirmation of others. Again, there are some, that are as destitute of honesty as the devil is of holiness, and will persevere in hopes of gain, and will grasp at every opportunity to take advantage, but when they are outwitted, they will exclaim against knavery and plead innocence. It is obvious to every person that it is among the ( 31 ) most vulgar and illiterate part of the world, where the capricious notions of witchcraft and hobgoblins reside. But in those parts of the world where learning and science prevail, every idea or pretension towards raising demons are excluded. The Laplanders, the most ignorant beings on earth, pretend to work miracles, raise demons, and predict future events, and many with weak intellects and tremulous, readily adhere to their fantastical declaration; but nature is uniform in her course, and deviates not, and when such wonderful phenomenon presents, as I have been treating of, we may reasonably expect that is the production and craft of vicious persons, to support their indolence. But the flexibility and readiness of man, to adhere to capricious declarations, when interests occurs, is very obvious, and impositions only proceed from a want of sagacity and deliberation, to investigate whether such propositions are compatible with philosophy or the course of nature. In the above mentioned occurrence, many eminent characters, possessed of morality and veracity, had the misfortune to be led captive in pursuit of anticipated riches, conducted by an inferior who was as destitute of honesty as Lucifer of holiness. But the prospects of wealth are often so enchanting as to exclude wisdom from the wise and discernment from the most sagacious. In the foregoing treatise. I have mentioned only the most eminent circumstances, accompanied with facts, as I thought it needless to advert to the more minute proceedings, for some of them were too simple to be exhibited to a continent where arts and sciences reside. But if it should be thought requisite, and would entertain the curious or illume the simple, with pleasure I would detail every particular manoeuvre, ( 32 ) that was transacted by the followers of imaginary hobgoblins. It is not from malevolence, or any antipathy, against any person or place, that induced me to write the above mentioned transactions, but purely to enlighten the minds of the simple, and free them from the imaginary fear of witches, apparitions and hobgoblins which do not exist. And as this relation proceeds from one that wishes happiness to all mankind, and the author, although unknown, hopes that no one person or persons will be offended at the relation of facts, when there are no names mentioned; providing they had an active part with the anticipating fire-club. This Pamphlet is chiefly intended for the perusal of the good economists in Morris County. Gentlemen, yours in amity,

PHILANTHROPIST.

|

|

from: The New Hampshire Sentinel, Dec. 23, 1820 To the Cheshire Money Diggers. For T.D. N. H. Sentinel. Who fears not to express, sirs, A wish, the work that you've begun, Might meet with grand success, sirs, To you who toil and dig so deep, In quest of earthly riches -- (Nor value sweat, nor loss of sleep) -- 'Mong devils, ghosts and witches, Who station'd are -- you know for what -- In shrouds, with ghastly features, To watch and keep each money pot From specie-loving creatures. -- To you, I say, much parise is due; Well may ye be rewarded; The awful scenes that you've been through, Deserve to be recorded. Tho' some crack jokes at you, and sneer, And swear you are deluded, Reason and Common-Sense, I fear, From them have been excluded. For he who doubts that Robert Kidd Came up our branch with shipping, And 'neath the soil his money hid, Deserves a hearty whipping! And other pirates too -- a score! Who've pillag'd on the ocean, To hide their booty far from shore, Might have a special notion. And rich old Bachelors, I ween, Full oft, inter their riches, -- No doubt their ghosts have oft been seen In petticoats -- or breeches; For they, good souls would take it hard If Charon should forbid, sirs, The blissful task, to stay and guard What they had earn'd and hid, sirs. You, knowing well that money lies Where misers hard, enshrin'd it; It is not a matter of surprise, That you should dig to find it. But when you've struck your circle round, By mineral rods directed, And excavated deep the ground, And come as you expected, Pat on a pot or chest of gold -- And hear it -- chink -- with pleasure -- And all prepared -- just taking hold, To raise the shining treasure, -- To have some little devil pop Right up -- when thus delighted! -- No wonder, faith, your honors hop, And leave the field, affrighted! -- To have e'en devil, ghost or witch Thus spoil your hopes -- I swear it! Is a provocative -- of which, There's few could grin and bear it. But when your spunk returns, and you Have held a Council, whether 'Tis best the trial to renew And win -- or die together -- Again return'd -- to find the gold Has took another station -- That, speechless, foodless, sleepless, cold, You've toiled ro win -- vexation! -- 'Tis then toy feel all o'er -- within -- A species of confusion; A kind of madness, with chagrin Which borders on delusion. It is, in sooth, a plaguy thing That mother earth is haunted By evil spirits -- smash and ding! -- And money pots enchanted! -- But so it is, in faith, or you Had known the miser's glory -- With friends enough, and money too. But e'er I end the story, I'd just advise your honors how To gain those golden riches -- 'Tis, Sirs, by digging with the PLOUGH! -- That's, uncontrolled by witches. Dec. 1820. PHILO PINDUS.

from: The Hallowell (Maine) Gazette,

Mar. 18, 1822

The tradition is, that vast quantities of money were deposited in various places in the earth, by the Buccaniers who infested our coast in the early settlement of the country. On these occasions one of the marauders, who had previously bound himself by an oath to guard the deposit, was killed and buried on the spot. The work at present is going on with much rapidity, and another excavation about [50] feet deep, has been made but a short distance from the first. "I conversed," says a gentleman who recently visited the spot, "with the old man who superintended the work, and found him tolerably intelligent upon other subjects. He uniformly evaded my questions which were put to him respecting the motives and expected results of this extraordinary enterprise. His son, however, a lad of 13, who shrewdly suspects they will have their labour for their pains, is more communicative. Having bribed him with a few coppers, he informed us that his father was first induced to undertake the business by a remarkable dream, which was repeated three nights in succession. After consulting an old woman in the neighbourhood, celebrated for her skill in the mystic art, an idiot, generally known by the appellation of "Greely's Fool," who, by the way, although he knows nothing of the material world, is reputed wise in all that relates to the invisible, he was confirmed in the belief of the existence of a subterranean treasure in this spot. Our young informant stated that many of the original partners in the concern had sold out their shares at an advance upon the first cost, and that others who are now concerned, have spent nearly all that they possessed."

from: The New Hampshire Sentinel,

Apr. 13, 1822

from: The New Hampshire Sentinel,

May 4, 1822

from: The Windsor Journal,

Jan. 17, 1825

A respectable gentleman in Tunbridge, was informed by means of a dream, that a chest of money was buried on a small island in Ayer's brook, at Randolph. No sooner was he in possession of this valuable information, than he started off to enrich himself with the treasure. After having been directed by the mineral rod where to search for the money, he excavated the earth about 15 feet square to the depth of 7 or 8; and all the while it was necessary to keep his pumps working to keep out the water. Presently he and his laborers came And heard it chink with pleasure, Then all prepared, just taking hold, To raise the shining treasure. Such is the story as related by himself. -- Whether he actually saw the chest, or whether it was the vision of a disturbed brain, we shall leave the public to determine.

from: The Orleans Advocate,

Dec. ?, 1825

By the rust on the kettle, and the color of the silver, it is supposed to have been deposited where it now lies, prior to the flood.

from: The Vermont Watchman,

Jan. 3, 1826

Now the main difficulty in the way of unsuccessful money diggers is this -- they do not understand the secret -- they neither dig at the right hour of the day, nor in the right place -- nor do they make use of the genuine mineral rod. No reasonable man doubts the fact that inexhaustable treasures lie hid in the earth; but they were desposited there at a more remote period and by a more bountiful hand than the misers of the fifteenth century. For the information of all future fortune-makers and money-diggers, we will reveal the grand secret, imparted to us by neighbors Careful and Successful, who have been digging money for many years, as the old lasy heaped coals of fire upon the heads of her enemies, shovel-ful after shovel-ful. The secret lies altogether in this -- don't dig too deep. The lucky hour is early in the morning, when the dew is on. The right place may be found on almost every upland or interval farm in the country by carefully observing these sure and never-failing signs of money in the earth, invariably indicated by the nature of the soil and the thrifty growth of a fine forest of sugar maple, red beech, black birch and the stately hemlock. And now for the genuine mineral rod. On this point the greatest of men and the gravest of money diggers have heretofore disagreed. While all united in the sentiment that it should be made of genuine metal, lest it point to the wrong place, one contended that the shape and construction of the rod should be straight, like an IRON BAR, -- another believed it would be best to add a lip at the end of the straight rod, to resemble a HOE, -- a third guessed it would be more likely to point at the ready-rhino, by adding the lip to a nose, like a PLOUGH, -- a fiurth verily thought that teeth should be inserted like a HARROW -- a fifth had a notion that the handle should be of wood, with two short arms of curved steel in the end, like a PITCH-FORK -- sixthly and lastly came forward neighbors Careful and Successful, who had been long in the practice of digging money, and absolutely declared, "to their own certain knowledge," that the right place was at they very bottom -- not of the ocean to be sure -- but that the only genuine mineral rod that would direct invaribly to the iron chest of dollars, had neither lip like a hoe, nose like a plough, teeth like a harrow, nor brains like a monkey -- but looked, O horrible! it looked -- just like a DUNG FORK. 'Tis done -- the long agony is over -- the secret is revealed -- and now that the ways and means of digging money are so plainly pointed out, no happy son of Adam, who owes the Printer, can for a moment hesitate what to do. -- With smiling countenances and grateful hearts, our generous patrons will no doubt flock to our office with the fruits and the compliments of the season, most sincerely wishing us, as we do them, a HAPPY NEW YEAR.

from: The (Rochester) Gem,

May 15, 1830

The charm was broken! -- the scream of demons, -- the chattering of spirits -- and hissing of serpents rent the air, and the treasure moved! The oracle was again consulted, who said that it had removed to the Deep Hollow. There, a similar accident happened -- and again it was removed to a hill near the village of Penfield, where, it was pretended the undertakers obtained the treasure. About this time the enemy's fleet appeared off the mouth of the Genesee, and an attack at that point, was expected -- this produced a general alarm. -- There are in all communities, a certain class, who do not take the trouble, or are not capable of thinking for themselves, and who, in cases of alarm, are ready to construe every thing mysterious or uncommon into omens of awful purport. This class flocked to the oracle. He predicted that the enemy would make an attack; and that blood must flow. -- The story flew, and seemed to carry with it a desolating influence -- some moved away into other parts, and others were trembling under a full belief of the prediction. At this time a justice of the peace of the place visited the oracle, and warned him to leave the country. He gravely told the magistrate that any one who opposed him would receive judgments upon his head, and that he who should take away the inspired stone from him, would suffer immediate death! The magistrate, indignant at the fellow's impudence, demanded the stone, and ground it to powder on a rock near by -- he then departed promising the family further notice. The result was the Smiths were missing -- the enemy did not land -- the money-diggers joined in the general execration, and declared that they had their labor for their pains -- and all turned out to be a hoax! Note 1: See the full article in The Gem, for a tie-in with Joseph Smith's family. -- A Rochester area treasure-seeking "Northrop" (Benjamin L. Northrop) is mentioned in connection with Zimri Allen's money-digging adventures on page 3 of George H. Harris' 1887 "Myths of Ononda." Harris' manuscript also re-tells the 1815 Rochester Smith family's story on page 6. Note 2: Although there are some good reasons for concluding that the 1815 Rochester Smith family was not that of Joseph Smith, Sr., the similarities remain striking. For example, the unnamed teenage son in the 1815 Smith family (Alvin was 17 in 1815!) was a seerstone-gazer, who had "become an oracle -- and the keys of mystery were put into his hands, and he saw the unsealing of the book of fate." Besides being a purported seer and oracle, Joseph Smith, Jr. is also supposed to have possessed supernatural "keys," as well as the ability to comprehend the mysteries of magic and religion. Harris' 1887 re-telling of the account adds: "the spirit showed him the great volume and putting the keys in his hands ordered him to open and read." -- Palmyra resident William Hyde recalled in 1888 that Joseph Smith had unsealed "Certain marks or hieroglyphics... [which] recorded the history of a highly civilized community that peopled this earth many centuries ago. No one could comprehend the meaning of the characters engraved on the tablets but young Smith... Hidden treasures would be revealed and everybody... would become the possessor of immense wealth... the 'keys' to everlasting riches..." Also, "that by means of the Urim and Thummim... Joseph [would reveal] the secrets of all arts and sciences..." This type of proto-Mormonism was also hinted at by Eliza R. Snow, who in 1829 wrote of an angel who spoke "of things before untold, Reveals what man nor angels knew, The secret pages now unfold To human view." Compare all of this with the fictionalized 1844 "angelic vision" of Parley P. Pratt: "the Angel... selected a small volume entitled: "A true and perfect system of Civil and Religious Government, revealed from on High"... I opened the book and read... I was about to read further, but was interrupted by the Angel... said he, 'you have now read all you are permitted to read at the present time.'" Note 3: The "Northrop" mentioned in The Gem article could not have been Benjamin L. Northrop (born in 1820); but there is good reason to conclude that the unnamed treasure-seeker was Ben's father, Miles Northrop (1778-1854). In 1830 a "Miles" lived in Monroe's Chili Twp. (adjacent on the West to Brighton -- where Benjamin L. Northrop resided); but this was Benjamin's cousin. A detailed account of part of Father Miles Northrop's farm and its situation in Brighton, can be found in "Charter and Others vs. Otis," an 1862 New York Supreme Court case, a summary of which was published in Vol. 41 of Reports of Cases in Law and Equity in the Supreme Court... In The Gem article Northrop is described as "so unlike anything of refined human kind, that he might well be called a demi-devil." This description matches well with the report given in the 1908 Northrup-Northrop Genealogy, which says he was a "Farmer and butcher... Insane for many years." According to Harris, Miles' son Benjamin L. Northrop also ended up insane.

from: The Rochester Daily Times,

May 28, 1851

The parties are some respectable citizens of the town of Brighton, whose nemos appear as witnesses in the report below, and one Francis Lambert and his wife who have resided in this city some six years. Lambert and his wife are French people, and the latter claims to be a "seventh" daughter born with a veil over her face, and gifted with the power of foretelling future events. We have had occasion to notice her operations before. It was she who furnished a verdant youth a few days since with a mineral rod to find gold upon a farm in Genesse county. She is a professional fortune teller, but of late has engaged in the "spiritual" business for the purpose of digging treasure. The parties who testify below applied to this woman some weeks since for aid in finding gold said to be buried on their farms in Brighton. -- She has been in the habit of going thither to a wheat field on one of the farms, and there convening with spirits, who directed the digging which has been carried on for several nights. It is said a hole some 30 feet square and 1t feet deep has been made by these money diggers. It will be seen by the testimony, that after Lambert and his wife had obtuined the $1000 in deposite from Northrop, the digging on his farm was suspended and [they] made preparations to leave for Canada. They were arrested last evening at the Landing just as they were about to take the boat. His money was recovered and the accused lodged in jail for examination. The parties appeared before Police Justice Moore this morning, and the following testimony elicited: -- Benjamin L. Northrop, sworn: -- Some time since I went and saw, this woman, asked her if there was any money on our farm. She looked in a stone, a diamond, and told me there was; she said she could go and get it, and I offered her one half. She said I must see her husband, I did so, and we agreed to go. We went out; she looked around, and found where it was. She said the spirits would talk to her if it was there. The first night they would not talk; the second night the spirits whistled; she asked the spirits to speak; asked them if there was any money there, they answered yes; have dug there six or seven nights; she then asked how much there was; the spirits said in one place 3 bushels, in another six bushels of gold; the female spirits said they would kill my horses. Mrs. Lambert asked the spirit if the money was good for the seventh daughter; spirit said no, it was not good; said I must raise one thousand dollars and give it to her; I told her to enquire of the spirit if notes deposited would be good; spirit answered her no, I must raise the cash; and it must be left at her house and not put in her hand as it would kill her dead. I raised the thousand dollars, and put into her bureau. -- She was to come on the next night and dig; she did so some two or three times, when the spirit said we must wait until the 26th of June. She said if we worked when the spirit talked it would kill. Wm. Cobb, sworn: -- After Northrop had been on once or twice, I entered the company. The first night I was there and dug, sbe was not there; next night she said if spirit spoke it would be all right, there would be something then, if not must give it up; had been there but a minute or two when there was whistling like a steam car whistle, and in the ground deep; she then asked the spirit if there was any money there, and it said there was. She asked how much, spirit said 3 bushels silver in one place, 6 bushels silver in another place; and 10 bushels of gold in another. Asked the spirit who that money was good for; spirit said for two; she talked in Latin to the spirt and the spirit answered in Latin; she said that the spirit said Northrop must give us a dollar a-piece for digging. Next night she told two of us to go and dig before she came; we did so when the spirit whistled once before she came; when she came she aaked what had been done. I told her the spirit whistled again; she told us to be quiet,and then went to talking with the spirit again. She asked it how long before she could have the money. The spirit said four weeks. --This was about the 15th of this month. The spirit said Northrop must raise $1,000. She said he must leave it with her. I came down to see her at her house. She said Northrop must bring the $1,000 or give up the businss -- she didn't care which. I told her it would be a risk to leave so much money with a stranger. She said "no danger." She said she would not lay her hands on it as it would kill her. She told me that Northrop told me to come and see her. I told her he did not. She said he stood on an eminence higher than I did, called me to his house and told me to go and see her. This was true, and I believed with more confidence what she said. Next night we took the $1000 and went there together with Mr. Pierce. All three went in a room. She said no one must see him leave it. We left him in a room so he could leave the money unseen. She said we must now leave the place where we had been digging, for four weeks. The spirit then told of another place where we went and dug. -- She said if we went to the old place the spirit would kill us. She told us to go on (if we dared and she would appear to us. She said the woman spirit was dying, and we must give her time to die and not go near the place. She looked in her stone and said the spirit's blood was going to the head, and it (the head) was all swelling up and looked as big as a hogshead. At the last place [the] spirit said the money was deep, and it would take six weeks to get it. It might be got sooner if they worked hard. The night after the female spirit threatened to kill Northrop's horses, I let him take mine to go after the woman. Shortly after reaching the ground they were hitched to the fence, we heard a noise and saw one of the horses down. The rail they were hitched to was broken square in two. The horses were much frightened. Daniel Pierce sworn: -- Was with the party every night. Heard the whistling. Mr. P.'s testimony accorded nearly with that of Northrop and Cobb. It appeared, however, that he had a diamond which he consulted, and had seen, he said, this woman in a stone, and she answered the description of one who was to assist in the search for treasure. He advised Northrop to go and get Mrs. Lambert. Mary Lambert examined: -- Have lived in the city 6 years. I was the seventh daughter, and was born with a veil over my face. I look in a little stone which I found when I was twelve years old, and see things, and then everything looks like stars, and I pray. I do not tell fortunes for money. I look in the stone for people and tell theem what I see, and they give me what they please. The residue of this woman s story was that she heard the spirits talk at Brighton and believed there was money there. She said that the $1000 was urged upon her by Northrop, and that she was only going to Oswego on a three week's visit. The magistrate required bail of Lambert and his wife, in default of which they were committed. The witnesses in this case seem to be fully impressed with the belief that spirits directed their operations in digging, and we think that they will not be likely to give up so. It would not be strange if they should follow her to the jail and here ask her aid in digging treasure. P.S.-- Since the above was written, we have heard from the Police Magistrate that Mr. Northrop came forward and bailed Lambert and his wife. Note: According to Dorothy Dengler, the same article also appeared in the Rochester Daily Democrat on May 28, 1851. She also mentions that "according to the Rochester Gem, Ben Northrop was one of Smith's friends who searched for the treasure" in Rochester during the War of 1812. from: The Rochester American, June 1?, 1851 Extraordinary Imposition and Credulity. -- [Recently] Mr. Benjamin L. Northrop, a farmer of Brighton [Monroe Co.], made complaint before Police Justice Moore, against Mrs. Mary Lambert, of this city, to the effect that she had swindled him out of $1000. It appears that Mrs. L. is a fortune teller, and converses with spirits -- not. by "knocking," but by words, whistling, and other vocal signs. She was applied to by Northrop, for her supernatural aid in discovering the whereabouts of several bushels of gold buried, as he believed, on his farm. Nothing loath, Mrs. L. undertook the job, but required Northrop to pay her in advance $1000 in cash, which he did. -- Having secured this handsome sum, she was of course in no haste to fulfill her part of the agreement, and was, in fact, on the point of leaving for Canada, when she was arrested. Fortunately the money was still in her possession, and on finding herself closely pressed by the strong grip of the law, she gave it up to the highly gratified Mr. Northrop. Who shall say that the dark ages of imposture and blind credulity are passed? -- Rochester American. Note: The above article appeared in the Rochester American about the beginning of June. It was reprinted, with slight variations, in the Cleveland Herald on June 2nd, and in the Auburn Christian Advocate on June 11th. |