unOFFICIAL JOSEPH SMITH HOME PAGE

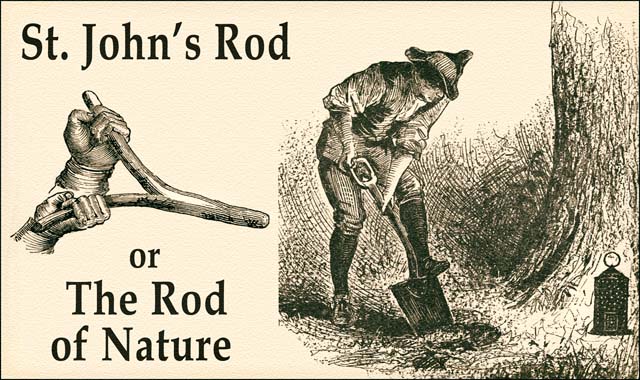

The AMERICAN RODSMEN

Divining Rods & Seerstones

Joseph Smith: (Illustrations & Photos) | (Maps & Images) | (NY Histories) | (Money Digging)

News Articles (1800s) |

Am. Jour. Sc. (1820) |

Quarterly Review (1820s) |

The Minerva (1825) |

Worcester Mag. (1825) |

Am. Jour. Sc. (1826) |

U.S. Magazine (1850) |

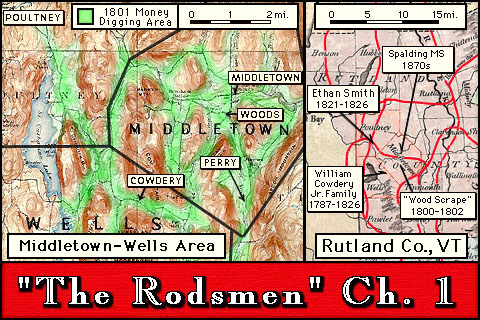

"The Rodsmen" (ch. 1) |

Mounds Mystery | Captain Kidd | American Israelites | Treasure Seekers | Gold Diggers

from: Misc. U.S. Newspapers

excerpt from: Petersburg Courier,

Jan. ?, 1815

The following are the results of experiments which have been made: 1st. A single twig of any tree, whatever, when newly cut will diverge a certain number of minutes or degrees from its proper position when brought directly over or in the immediate vicinity of any conducting substance, such as metals or water. But the best conductors for electricity and galvanism are not the best for the divining rod. Water is found to be more powerful than any of the metals, and salt water still more powerful than fresh. The degree of attraction also depends considerably upon the substance interposed between the conductor and the divining rod. 2d. Although a twig from any tree will prove the experiment -- yet some trees are found to answer much better than others -- the branch of the peach and the cherry tree are said to be superior in this respect. A forked twig will also diverge more powerfully than a single twig. 3dly. If the twig be suspended by an electric, or in immediate contact with an electric, no divergence will take place. 4thly. The angle of divergency depends in a great measure upon the nature of the conductor which is used. -- The human body is found to produce a greater degree of divergency than any other substance -- and the bodies of some individuals produce the effect in a most surprising degree, while in other individuals the action is scarcely perceptible. The effect is also found to vary with the state of the system. What appears most surprising is, that in the same individual the greater the state of debility, the greater the effect produced. If the skin of the human body be moistened, particularly those parts in immediate contact with the divining rod, the effect is much increased. Salt water or a weak solution of muriatic acid, has been found to be the best fluid for this purpose. 5thly. The most effectual mode of using the divining rod, is as follows: The operator to be bare footed in making the experiment -- and to have the soles of his feet and his hands well moistened with salt water, or such a solution of the muriatic acid, as will not prove disagreeable. The divining rod to be a forked twig of peach, cherry or hazel tree. He holds the extremity of each fork by one hand, in such a manner that the twig may rest in a direction nearly perpendicular to the horizon, having the cut extremity upwards. The operator holding the twig carefully in this position, walks slowly forwards, and so soon as he approaches any subterraneous water or metal, not more than twenty feet below the surface of the earth, the twig begins to turn or bend forwards. If the metal or water be but a few feet below the surface of the earth, the twig turns entirely over with the extremity pointing towards the earth. The same effect will take place with many individuals without being barefotted -- but if the above precautions be taken, the experiment will succeed with every person. 6thly. If the operator in making the experiment, has silk stockings, or uses silk gloves, no effect will be procured. The divining rod has been practised in the western country for many years with the greatest success in the finding of water; and there are several gentlemen of the first respect in Kentucky, and whose veracity is unquestionable, with whom the experiment invariably succeeds. There are also two gentlemen in Richmond, who are well known, would never attempt to impose upon the public, equally dexterious in the use of it. Those are the Reverend John D. Blair, and Mr. John Foster. The latter I have seen myself make the experiment. The European theory to explain the phenomena of the divining rod, is chiefly this. The conductor, whether water or metal, is supposed to form with the superincumbent earth and the fluids of the human body, a galvanic circle, and the more perfect this circle is, so much the more powerful will be the action of the divining rod. Thus what was regarded only a few years ago as a deception practised by impostors and the credulous, is now cultivated, improved, and made the study of men of science.

excerpt from: Washington National Intelligencer,

July ?, 1820

excerpt from: Windsor Journal,

Jan. 17, 1825

excerpt from: Montpelier Vermont Watchman,

Jan. 3, 1826

Note: The above excerpt was, of course, meant as a joke and a put-down for the generally "unsuccessful money diggers" of New England. Mineral rods in the early 19th century were inevitably cut from live wood, and not fabricated from metal. See also the somewhat similar, humorous poem published in the Keene New Hampshire Sentinel of Dec. 23, 1820.

excerpt from: Pittsburgh Recorder,

May 26, 1826

excerpt from: Pittsburgh Recorder,

Oct. 3, 1826

excerpt from: Middlebury Vermont American,

May 7, 1828

excerpt from: Palmyra Reflector,

Feb. 1, 1831

Note: This appears to be the first published association of Joseph Smith, Jr. with a "mineral rod" or a "divining rod," (although he is not definitely credited with its use). A more reliable early account of Smith family members using a divining rod can be found in Peter Ingersoll's statement of Dec. 2, 1833. There is some evidence (from a later period) indicating that young Smith may have evolved in his seership, from an initial use of forked sticks to consultations with peepstones -- and, eventually, to direct epiphanies that required no magical apparatus. See Mark Ashurst-McGee's 2000 Utah State thesis, "A Pathway to Prophethood: Joseph Smith Junior as Rodsman, Village Seer and Judeo-Christian Prophet."

excerpt from: Woodstock Vermont Chronicle,

June 24, 1831

excerpt from: Fredonia Censor,

Sept. 14, 1831

excerpt from: Boston Christian Watchman,

Nov. 9, 1832

excerpt from: New York Commercial Advertiser,

July 25?, 1836

excerpt from: Hudson Rural Despository,

Nov. 5, 1842

excerpt from: Chicago daily Tribune,

Sept. 9, 1877

excerpt from: Boston Daily Advertiser,

July 11, 1879

excerpt from: Montpelier Cincinatti Daily Gazette,

Aug. 16, 1879

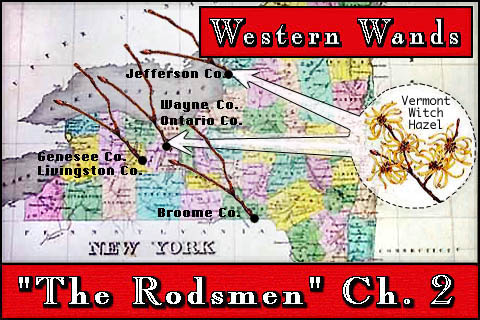

The divining rod is an implement of unknown antiquity. It is probably older than any traces remain of its employment; and there are at this day persons of some pretensions to science who are, from what they consider evidence of their own senses, firm believers in its efficiency.... The divining rod is most frequently used for the discovery of water; and there is no denying, that, in many instances, water has been found in the places where it seemed to indicate its existance. But as search is seldom made for water, by the use of the diving rod, except in localities where there are other reasons for suspecting its presence, the instances of apparent success through its instrumentality must, until the contrary is shown, be set down as coincidences. The characteristic circumstance in the phenomena of the divining rod would seem to be the fact that it "works" in some hands and does not work in others. That, in the hands of some, the index of the implement does appear, to the holder, to be drawn forcibly from its perpendicular, while in those of others, under precisely the same circumstances, no such tendency is perceptible, is not without withholding all faith in human veracity -- to be denied. Now if there were really a mutual attraction between the divining rod and some exterior substance or element, this difference would not occur; at least there is no known warrant for its occurence. From wherein, then, does it arise? Modern science seems to afford the answer. Between the muscles of voluntary and the muscles of involuntary motion the distinction is not absolute. Under the influence of particular physical conditions, the former, in persons In whom the imagination predominates, exert forces of which the indIvidual is altogether unaware. From special states of mind, of which the party may be entirely unconscious, there results special muscular activities and inactivities; the latter often taking the form of decrepitudes which, originating in no physical infirmity, baffle the efforts of the most experienced for their removal. The person in whose hands tbe divining rod "works," while doing his utmost, with his conscious will and one set at muscles, to keep the staff of the instrument in an upright position, is resisted by a more potent automatic volition of which he is unconscious, which has, under its command, another set of muscles, by which the strength of the first is subdued and overome. The final cause, it may be, of this capacity for a duplicate and antagonistic manifestation exists in the fact that there are two brains, each capable, under special conditions, of acting independently of the other, while there can be consciousness of the operations of only one of them at a time. Ordinarily there is little art in the construction of a divining rod; any green branch that divides equally being employed. But for special purposes there are special recipes, savoring of the relics of magical ideas and practices. I remember one that was constructed for the express purpose of searching for "Kidd's money," on the islands of East River, near the city of New York, in which inquest several persons whom I knew were engaged.... A traditional rule... for the construction of the mystical implement which was to assist in the discovery. This was a fork of witch hazel, which, in its natural position, divided north and south, so that the sun passed over the point of intersection, and which had been cut at sqme particular lunar aspect or planetary conjunction. The stock was about a hand's breadth in length and an inch in thickness, and the branches each about an inch long and half an inch in diameter; fastened to each of which was a thin slip of whalebone ahout eighteen inches in length....

excerpt from: Montpelier Vermont Watchman,

Oct. 26, 1887

excerpts from: Oakland Naked Truths About Mormonism,

Jan.-Apr., 1888

Christopher M. Stafford' Statement I was born in Manchester, Ontario Co., N.Y., May 26, 1808. I well remember about 1820, when old Jo Smith and family settled on one hundred acres one mile north of our house... Jo [Jr.] claimed he could tell where money was buried, with a witch hazel consisting of a forked stick of hazel. He held it one fork in each hand and claimed the upper end was attracted by the money... |

from: American Journal of Science -- 1820 -- Art. XVII. -- On the Divining Rod, With Reference to the Use Made of it in Exploring for Springs of Water. [102] ...letter to the Editor, dated

NORFOLK, (Con.) Oct. 23, 1820.

Remark -- Every person, in the least conversant with the objects of a scientific Journal, must be aware that an Editor is, in no case, answerable for the opinions of his correspondents. We are willing to preserve all well authenticated facts respecting the divining rod, although we have the misfortune to be sceptical on that subject: perhaps, however, we ought in candor to add, that we have never seen any experiments. Those so often related by the ignorant, the credulous, the cunning, and the avaricious, are, in general, unworthy of notice; but when attested by such authority as that of the Reverend gentleman, whose name is attached to this letter, they will ever command our ready attention. Dear Sir, I am highly pleased with your Journal of Science; and doubt not of its being at once a source of instruction and an honor to our country. Permit me to suggest the propriety of inserting an article, embodying a sufficient number of well authenticated facts on the use of "mining rods" in discovering fountains of water under ground -- to put their utility beyond a doubt. I presume that yourself or some of your correspondents are already in possession of such facts and could easily furnish the article. For myself, I was totally sceptical of their efficacy, till convinced by my own senses. [103] My class-mate, the Rev. Mr. Steele, of Bloomfield, N. Y. called on me a few weeks ago, and in conversation on the subject, informed me that the rod would "work" in his hands. A twig of the peach was employed on the occasion. It was at once manifest that it bent and often [withed] down from an elevation of 45 degrees to a perpendicular in some spots; and when we had passed them, it assumed its former elevation. At one spot in particular, the effect was very striking, and he at once said there must be a very large current of water passing under that place, or it must be very near the surface. I informed him that a large perennial spring issued at the distance of perhaps fifty rods, and requested him to trace the current, without informing him of the direction of the spring. He did so, and it led him nearly in a direct line to the spring, which was so situated as to prevent his discovering it till within one or two rods of its mouth. The mode of his tracing it resembled that of a dog on his master's track crossing back and forth, and he proceeded with as little hesitation. The result however inexplicable removed all my doubts. It was in vain for me to reply against the evidence of my senses, by saying, How can this be? and why should not these rods operate in the hands of one as well as another? On a journey to the south-east part of New Hampshire, I found a practical use has been made of these rods in that region, for a year or two past, in fixing on the best places for wells. A man in that vicinity could not only designate the best spot, but could tell how many feet it would be needful to dig to find water, and had frequently been employed for this purpose without having failed in a single instance. I will recite one case out of a number. A man who had dug in vain for a good well near his house, requested his advice. On experiment with the rods, the best place was found to be directly under a favorite tree in front of the house; and there the proprietor was assured he would find abundance of water at a moderate depth. But on reflection, he was loth to sacrifice the tree, and concluded it would answer as well to dig pretty near it. He dug; and after sinking the shaft much deeper than had been directed, [104] abandoned it in despair. He soon complained of his disappointment. "Did you then dig in the precise spot I told you?" "I dug as near it as I could without injuring the tree." "Go home and dig up that tree, and if you do not find water at the specified depth, I will defray the expence." He did so; and obtained an excellent well at the given depth. As to the depth, it occurred to me at once, when seeing the operation of the rods in the hands of Mr. Steele, that it might be easily ascertained, by taking the angle they made at a few feet from the spot where they became directly vertical; and this, I conclude, is the mode of ascertaining it, though I was not informed. Let me also mention a fact in optics, which I have not before witnessed, and which occurred to me when travelling recently in company with a friend. As we were descending the hill perhaps two miles this side of Tolland, we were admiring the fine view of the highlands, which are seen stretching from north to south on the west of the Connecticut. All at once, the northern half of the range appeared to change from the brown hue of an autumnal forest, to a bright and beautiful green, resembling the verdure of a rich pasture in the spring, or a distant wood of deep evergreens. But after descending a few rods further, it assumed its native aspect. The sun, about three hours before setting, was then shining very brightly on the range, and the sky clear, though damp. I conclude the effect was produced by the particular angle of reflection, and the state of the atmosphere. Yours with respect,

RALPH EMERSON.

P. S. -- One morning, we witnessed a beautiful exhibition in nature, of the "sun's drawing water," (as it is commonly termed,) produced by the shadow of a copse on a hill, projected across a valley filled with a dense fog. It led me to conclude, that that appearance is never produced except in clouds of so thin a texture that the sun can shine through them -- contrary to what I had before supposed. But you are too familiar with so common a phenomenon, to need any remarks upon it from me. R. E. Note 1: The "Rev. Mr. Steele" who demonstrated a knowledge of the workings of the divining rod was evidently the Rev. Julius Steele (1786-1849) who ministered for the Congregational Church in Bloomfield township, Ontario County, New York from 1815 to 1828. In 1830 Bloomfield township was split into East and West Bloomfield. West Bloomfield borders Mendon township and touches Victor township, in Monroe County, (the area where Brigham Young and Heber C. Kimball joined the LDS Church in 1832). East Bloomfield touches Farmington township, which was split into Farmington and Manchester in 1821. Manchester was the boyhood home of Joseph Smith. It seems more than likely that both Brigham Young and Heber C. Kimball (who were wont to attend all sorts of relgious meetings, camp meetings, etc., in their neighborhood) knew Rev. Julius Steele prior to his departure from their neck of the woods in 1828. According to Mormon historian D. Michael Quinn, Brigham Young and Heber C. Kimball were no strangers to the operation of divining rods. See Quinn's "Latter-day Saint Prayer Circles" in the Fall 1978 issue of BYU Studies, where the historian says "during the Nauvoo period Apostle Heber C. Kimball 'inquired by the rod' in prayer," etc. Note 2: Heber C. Kimball's parents, Solomon F. Kimball and Anna Spalding Kimball, moved from Sheldon, Vermont to Bloomfield township, Ontario in 1811 and young Heber lived there until 1820. Solomon F. Kimball is listed in the 1820 Ontario Co. Federal Census as living in Mendon township, just north of West Bloomfield. Rev. Julius Steele is listed on page 379 of the 1820 Ontario Co. enumeration for Bloomfield -- the page previous lists the Moses Fairchild family and page 376 lists Sally Fairchild's family, among whom was William Buell. Fairchild. Oddly enough, the 1820 listing shows Sally Fairchild and Rev. Julius Steele living in close proximity to members of the Alger family, probable close relatives of Samuel Alger and Clarissa Hancock Alger, the parents of Joseph Smith, Jr.'s first plural "wife." Another near neighbor was Alpheus Cutler (later a notable Mormon), along with various members of the Hamblin, Noble, and Buell families. Joseph Bates Noble's father once worked for one of the Bloomington Fairchilds. For William Buell. Fairchild's recollection of early events in Bloomfield, the origin of Mormonism, etc. see his 1845 article, "Mormonism and the Mormons." Note 3: It appears unlikely that the "Ralph Emerson" who contributed the above letter to Silliman's Journal was the famous Ralph Waldo Emerson. The correspondent says that Julius Steele was his "class-mate." Rev. Steele graduated first from Yale College in 1811 and then from Andover Theological Seminary in 1814, while Ralph Waldo Emerson attended the Boston Latin School and graduated from Harvard University in 1821. On the other hand, a Rev. Dr. Ralph Emerson (1787-1863) graduated from Yale College in 1811 and later became a professor at Andover Theological Seminary.

-- 1826 --

[201] Observing men have long been perplexed with the divininig rod, that common discoverer both of salt water and fresh, and of minerals and ores in the bowels of the earth. Those who at once laugh at its pretensions and always laugh at them, make light of the perplexity, without taking a step towards its removal; while those who have paid any attention to the subject, find facts irreconcilable with any known and established laws of nature; and, also, reasonings contrary to known laws and to common sense. If the laws of the divining rod be an absurdity, it is equally an absurdity that honest men should combine to maintain a poor falsehood. Since the eleventh century the divining rod has been in frequent use. It was first employed "for the purpose of finding metals and minerals, and for the discovery of stolen property, and to identify characters guilty of crimes." Justice coming to be better understood, the divining rod lost credit as a witness of moral turpitude, and now claims, and has long since only claimed, to find metals and ores and fountains and veins of water below the surface of the earth. More than one English writer has spoken kindly of the esteem in which it has been held by the miners of Britain. In France, so late as 1781, a volume was published, 'detailing 600 experiments, made with all possible attention and circumspection, to ascertain the facts attributed to the divining-rod; by which is [202] unfolded their resemblance to the admirable and uniform laws of electricity and magnetism.' We find in our own country, many decided friends of the divining rod. Our public journals not unfrequently contain letters of respectable correspondents, stoutly maintaining its character for truth and integrity. It is a subject of eager curiosity to some, and is not perfectly understood by any. It admits of being explained to the most moderate capacity; and it is hoped this paper will furnish every reader both with facts and arguments, to sustain him in right views of the divining rod, and to enable him to disprove the false. It begins with a description of the rod, and a general notice of the present state of the art in our own country. The divining rod is a forked branch of any tree whose bark is smooth and whose fibre is very elastic. The witch hazel is in the highest esteem, not merely for its potent name, but also for the convenient size and ready forks of its plenteous branches, and the uncommon elasticity of its fibre. The peach and the cherry are often used. The limbs of the fork should be 18 inches or 2 feet in length, and of the diameter of a pipe stem. When used, it is taken thus: [graphic - not copied] the palms of the hands being turned upwards. But when the diviner, apprehending the action of the hidden influence. [203] begins to grasp the rod firmly, the fingers are drawn tightly upon the rod, and it takes this form: [graphic - not copied] the limbs of the rod being bent from their middle to their lower extremities outward. The diviner, holding the twig carefully in this manner, moves onward with a slow and creeping step. In due time the head of the fork turns downwards, and, coming to point perpendicularly to the earth, marks the site of the fountain or ore. The action of the rod under these circumstances, is a fact plain to the vision of every beholder. Those who hold it, are oftentimes men in whose hands we would without hesitation intrust life, property and reputation: and no doubt they are wholly unconscious of the power, which excites the action of the rod, but they confidently believe it proceeds from hidden fountains, or minerals in the bowels of the earth. From north to south, from east to west, the divining rod has its advocates. Men in various callings, men above the reach of mean arts, men of the soundest judgment, of large information, and of the most exemplary lives, do not disown the art, and when a friend demands their aid, rarely if ever, is it made the means of extortion by the meanest professor. Literati and Doctors, in want of fountains for their domestic use, do not disdain to call for the demonstrations of the divining rod, and will, in some instances, acknowledge the accordance of the results with the previous declarations of the diviner. If there be a fraud, the diviners themselves are the first deceived, and the greatest dupes. But how can they be deceived? They hold the rod steadily in both their hands -- in the diagram, the point of the rod is turned towards the heavens. [204] In searching, the rod discovers its sensibility by the motion of the point from its vertical position downward through the arc of a semicircle, ontil it rests perpendicular to the earth. This motion, so far from being intended by the holder of the rod, is made in opposition to the closest grasp his hands care give. And although an honest man's word might be taken for this, we have the fact corroborated by our own senses. We can see, and if that be not enough, we can also feel the rupture of the green bark, as it is fairly wrung from the rod, in the contest between the force which bears the point of the rod down, and the pinching grasp of the diviner, to prevent that motion. The rod does not exhibit this unaccountable action in the hands of every man. Many, all, can urge it to exhibit this motion; while it is only in the hands of a very few that it is supposed to move not merely without urging, but contrary to their best efforts. (One writer says: With the precaution of washing the hands and soles of the feet in a weak solution of muriatic acid or salt and water, and making he trial barefooted, the experiment will succeed with every one.) These few are of no peculiar age, constitution or habits, to distinguish them from their fellow-men. But if any female has ever exercised the gift of divining by the witch hazel, it has not come to the knowledge of the writer. Diviners are sensible of no change in their feelings, while the rod acts. They determine its nearness to some attracting body, as every beholder may, solely by the demonstration of the rod itself. The only peculiarity Ihave heard commonly remarked, is, that the rod acts more freely in hands naturally moist, than in hands naturally dry -- a mechanical effect which oil would probably increase. In New-England, where springs are most abundant and always pure, the use of the art is less frequent, because less necessary. In the states south and west, where water is not equally abundant, and fountains are not so certainly pure, the art is better known and more highly valued. The water hunter obtains celebrity. He is sent for to a great distance, and performs wonders with praiseworthy modesty, and for a moderate compensation. In all parts of the land, if the diviner hunt for metals, he becomes distrusted by the better sort of men. Yet the persuasion is general, that the rod is influenced by ores; and this persuasion is the diviner's greatest defence. "For in pursuit of water, if he direct the search at a wrong place, he is [205] excused without loss of confidence, upon the discovery of any mineral or vile ore in sinking the well. Traces of iron ore are almost universal in that part of our country, where the divining rod is in the highest repute; and often serve effectually to conceal the diviner's entire defeat. But the divining rod does not merely point out the site of the hidden fountain: it determines also its depth. This part of the science is equally wonderful and important. To know that water may be obtained by digging at a particular spot, is not enough. We must know more; that the fountain is within a reasonable depth. Accordingly, all men gifted with the use of the divining rod, have a way to determine the depth of the newly discovered fountain, if it be within fifty feet of the earth's surface. Thus the inexplicable motions of a green twig in the hands of a rare man, serve, in the opinion of many, to point out the situation of a fountain in the midst of the dry land, and to ascertain its depth; and to point out veins of salt water with precision from 300 to 600 feet below the surface of the earth. The thing is incredible; and it is equally incredible that the best men. in the land should falsely maintain that the motions of the rod in their hands are entirely contrary to their own well-meant efforts. In 1820, I was at the residence of a respectable farmer in Ohio, and again in 1821, where I noticed a new well at an inconvenient distance from the house. I inquired why that spot had been chosen for a well. The farmer replied, that it had been selected by the dividing rod. "Ah! and who carried the rod?" He named the father of a large family, one of thirteen brothers, and respected throughout the country. Here was food for curiosity. The well was but 7 or 8 feet deep, a triumphant witness to the power of the divining rod. (* No sign of a fountain, dissoverable to common view, existed at the spot before sinking the well. The diviner told the precise depth it would require to reach the water: so said the farmer.) On learning further that the rod marked perfectly well in the hands of one of the farmer's eight sons, I obtained leave to take him with me, and make experiments. The lad was about 12 years of age, and his character of a diviner was established, where that of a prophet is last allowed: in his own family and among his own kindred. His youth was no reasonable objection to his possessing a peculiar natural gift; and I hoped now to determine, whether the cause of the motion [206] of the divining rod lies above or below the surface of the earth. We first prepared divining rods from every species ot shrub and tree in the forest, the orchard and the garden, to determine the kinds of wood which are most apt for divining. We then repaired to the grass plat, in which the new well was situated; for there the rod, when held by experience, had already designated the situation and general course of three veins of water, which the lad might retrace with more certainty, than he could designate a new fountain. A swift brook runs on one side of the enclosure. The first experiment was to know, whether the rod would exhibit its singular movement in my hands. It would not. The next was to find what notice it would take of water running above ground. The lad held the rod naturally by its limbs parallel to the surface of the swift brook. But the point made not the slightest dip to discover its affinity for water. Then the lad held the rod in the diviner's manner, sometimes standing in the water, and continued standing on stones raising him above the water. After many trials with contradictory results, the boy thought that the brook attracted the rod in some degree, but not so much as a vein of water under ground. We next turned to the hidden veins of water, on one of which the new well was situated. No one has ever supposed that the attraction between the rod and hidden fountain communicated through the eyes of the diviner. It was clear that these guides of his steps must be quite unnecessary to the lad in retracing the hidden water-courses, if I would gently lead him myself. For the rod is not an eye-servant, to fail of noticing its proximity to hidden fountains, because its master fails to watch its motions. I explained my purpose to the lad, who readily consented to further it. He traced the three hidden veins over the space of an acre, while I, following close behind him with a heavy stick, tore off the light turf, and made a continued furrow along his course. While thus employed, I repeatedly asked him, if he surely found the veins as the aged man had done; and to his constant answer in the affirmative I replied, that any mistake now would render it impossible for him to retrace his path blindfolded. This done, I blindfolded him so that he could not see, -- took him lightly by the elbow, and led him away from the [207] furrow marking the vein of water on which the new well had been sunk. After a few steps, I turned with him, requesting him to hold up the rod for discovery. I guided him back, but he chose the time of every step. The rod began to turn, and, when having finished its circuit it turned perpendicular to the earth, he stopped. "Do you mean that the rod points exactly to the vein of water?" "Yes," he replied. And indeed it did: with his eyes he could not have pointed it better. This was demonstration. Conviction could neither be resisted nor avoided. The sight of the new well had prepossessed me in favour of the divining rod. The experiment with the lad had been conducted fairly, and its result was irresistibly conclusive. It must convince every one: and to obtain a collection of facts which would put the question at rest forever, I continued the experiment. I led the lad to the next furrow, and the rod missed it. I led him back, and it missed again. I led him to and fro, across and then along his three furrows; and he failed incessantly. I tore off the turf at every new place, where the rod pointed out a fountain, and ceased not from discoveries, until the russet and bleached turf of the acre on which the experiment was conducted, became figured with black spots, denoting fountains every where. This was as it should be. There could be no mistake. The illusion of the fountains, and of all attraction under ground, vanished at once. The motion of the rod remained, but it must be accounted for some other way. In all my experiments with diviners since, I have found them very shy of a blinder. No diviner has proved so traitorous to his own self-respect as to test the skill of the rod by depriving it of the light of his own eyes. One whose age and respectability obliged me to pay him deference, was pleased with the suggestion of trying the rod over running water above ground. Across a neighboring stream, a huge tree had been prostrated; its capacious trunk serving for a firm pathway over the swift waters. On this the good man crossed the brook, holding the divining rod properly in his hands. As he came over the waters, the point of the rod began to turn, but did not reach the end of its motion, until he had fairly crossed the stream, and stepped upon the opposite bank. In repeating the experiment, his own motions and those of the rod were better timed together. His conclusion, carefully drawn, was, that the rod was affected by running water above ground, but not so much as by water under ground. [208] He held the rod with peculiar spirit, and an air of determination. Hoping to catch his lively manner, I took a rod, as I stood on the bank of the rivulet, and tried my own hands again. I moved neither hand nor foot, but the rod was in action; neither could I restrain it. He who has held the Leyden jar in one hand, while, for the first time in life, he received its electric charge with the other, will recognize the sensation which communicated itself to the heart, when I felt the limbs of that rod crawling round, and saw the point turning down, in spite of every effort my clenched hands could make to restrain it. To my great satisfaction, without moving from the spot, I found the bark start and wring off from the limbs of the rod in the contest; just as the diviner often shews, to convince himself and his employer of the strong attraction of the discovered fountain. It was manifest that the force moving the divining rod is unconsciously applied by the hands of the diviner, and that the great art in holding the rod consists in holding it spiritedly. A smooth bark and a moist hand appeared to have a substantial connection with divining; and from that day to this the rod has never failed of moving in my hands, nor in the hands of those I instruct. Take the rod in the diviner's manner, and it is evident that the bent limbs of the rod are equivalent to two bows tied together at one extremity; and, when bent outwards, they exert a force in opposite directions upon the point at which they are united. Held thus the forces are equal and opposite, and no motion is produced. Keep the arms steady, but turn the hands on the wrists inward an almost imperceptible degree, and the point of the rod will be constrained to move. If the limbs of the rods be clenched very tightly that they cannot turn, the bark will burst and wring off, and the rod will shiver and break under the action of the opposing forces. The greater the effort made in clenching the rod, the shorter is the bend of the limbs, and the greater the amount of the opposite forces meeting in the point: and the more unconsciously, also, do the hands incline to turn to their natural position on the wrists. And this gives true ground for the diviner's declaration: the more powerful his efforts are to restrain the rod, the more powerful is its effort to move. It would be absurd to suppose, as he does, that the fountain or mineral increases its attraction, in proportion to the resistance he opposes to the motion of the rod induced by that attraction: and he never once suspects, that the very effort to [209] restrain the rod is so applied by the unnatural position of his hands, as to become itself the sole cause of the rod's motion. Let the diviner release his grasp, and the rod can no more turn itself in his hands, than the unbent bow can throw an arrow. By grasping the rod smartly, he strains the bows; and if the rod be small and elastic, and of a smooth bark, it will weep round in moist hands slowly and mysteriously. -- But if the rod be large, and otherwise properly qualified, its limbs are too stout, and its motion, when smartly bent, becomes ungovernable. This renders a small rod essential to the diviner; a rod whose motions he can bridle, but not wholly overcome. The motion of the divining rod forwards rather than backwards, is produced by the slight turn of the hands on the wrists towards their natural position. The rod may be mad with perfect ease to turn backwards rather than forwards, only by turning the hands still more upward. This motion of the hands on the wrists is not observed by the diviner, but if he mark the position of his hands in the commencement, and again at the end of the experiment, he will find it apparent. Two large goose quills tied together at their tips, and held like a divining rod, are a fine test of the nature of this moving force. Two sticks of polished whalebone, flattened and joined at one extremity, form a perfect divining rod. The motions of these quills and bones are as perfect for the discovery of fountains as those of any green branch ever cut. Indeed, polished whalebone excels witch hazel itself in divining, as it is firmer, smoother, and more elastic. But polished whalebone has neither sap nor juices to be attracted by metals nor by fountains. (Since writing this, I have learned that a professional gentleman, a most excellent man, and a well-known diviner, not many years deceased, commonly used a fork of whalebone for a divining rod.) The laws by which the depth of the discovered mines of fountains is supposed to be determined, are a curiosity sufficient to attract a moment's attention. There is something amusing in the oddity of their moonstruck features; but it is a sober and a melancholy sight to see a good man working by them, wise men confounded by the results, and the multitude inclined by the whole operation to trust in superstitious observances. [210] The diviner, having ascertained the site of a fountain, and wishing to determine its depth, makes it a centre from which he retires to some distance, and returns again very slowly with the rod on the search. The moment the rod is perceived to move, he stops and marks the ground. He then retires from the centre in another direction, and carefully approaching again, he marks the ground where the rod is first moved by the supposed fountain. Repeating this several times for the greater certainty, he makes it appear that the rod is every where affected within a circle, whose centre is the site of the fountain; and the diameter of this circle is precisely twice the depth of the fountain required. If the water be 7 feet below the earth's surface, the rod will be affected in a circle of 14 feet diameter; but if the water be seven times seven feet deep, the rod will be affected in a circle seven times greater than the first. The attraction extends with the distance! It is absurd. The deeper the fountain lies, the sooner the rod will discover its existence I It is most unnatural. Moreover, the amount of the attractive forces is always just sufficient to draw the point of a rod through the arc of a semi-circle, and no more; whether the attractive forces be expanded throughout a circle of 100 feet diameter, or compressed into one 14 feet diameter. Then these forces ought to be very active, when the circle is reduceed so as to bring the atracting bodies into near contact. But after they come in sight of each other, all mutual attraction ceases, and they remain at rest! I am unable to say what law is used to determine the depth of salt-water fountains. That which remains to be noticed is more applicable to their case, than the law already expounded. It would extend the first rule too far for the simplest understanding, to suppose, that a salt-water fountain, 300 feet deep, would influence the divining rod in a circle of 600 feet diameter; and that a fountain 600 feet deep would influence the rod in a circle of 1200 feet diameter. This second law, however, was invented before salt-water fountains of that depth were discovered, and is extensively known to diviners, and for variety frequently used. It can be deduced from the manner of operation, which is this: the diviner holds the rod by the extremity of one of its limbs, extended over the discovered fountain or mine. In this situation the point of the rod is exposed to two conflicting forces, viz: the attracting body, and the elasticity of the rod. In the contest [211] between these, the rod vibrates, and the number of its vibrations is the depth of the attracting body, not in yards or inches, but in running feet! Such are the laws of the divining rod; and such their boasted "resemblance to the admirable and uniform laws of electricity and magnetism." Some good men will yet be reluctant to surrender the divining rod; to rank it among the monstrous births of the dark ages which yet survive. They will urge instances of its successful operation: they will assert, and perhaps prove, that fountains have been and are discovered according to the predictions of the diviner. They will take particular notice of the exactness with which the blinded boy struck the vein of water the first time, and be almost ready to suspect that the natural incertitude of mind, peculiar to one led about blindfolded, communicated itself to the divining rod, and caused its mistakes. That the lad succeeded perfectly the first time, ceases to be a wonder, when it is recollected that afterwards he failed incessantly. Possibly he kept some count of his steps, to aid him in the first trial, and then became bewildered. He should be bewildered. He ought not to know north from south, but only that the ground he would tread on was safe. Then his mystical rod might have ceased to move, if it were not where the waters were. But it did move, and point most knowingly. And if the young fox had had his eyes, I doubt not that in fifty trials, the rod would have pointed more than twice in the same place. I am not one to believe that a series of coincidences on the same point is often accidental. If fountains have been and are discovered according to the predictions of the diviner, (which I allow,) it is because, in this country, men can hardly fail of finding water in from 20 to 50 feet deep, any "where: they cannot miss oftener than diviners actually do. That sometimes the diviner hits the truth closely, as in the case of my farmer's new well, I shall not deny, when others honestly assert the fact. But they do sometimes mistake altogether; and their failure being no wonder, is soon forgotten, while their success is matter of astonishment long to be remembered. After a faithful and patient investigation, I know not the slightest ground on which the claims of the divining rod can be sustained one moment. I allow to the utmost, that the [212] motions of the rod take place contrary to the sincere intentions of the diviner. But the same force which he applies to restrain the motion, does, actually, from the peculiar manner of holding the rod, compel that motion. If the attraction between the rod and water be real, it will show itself, one would think, when the rod is held fast in the diviner's hands, in any position. This, however, is not the case. It requires a smart binding pressure of its limbs, together with an imperceptible turning of the hands on the wrists, to put it in action; and then the more you hold it, the more it will go; This singular conduct of the rod has imposed on diviners, and, mistaking its true origin, they have, with common consent, imputed it to ores and fountains in the bowels of the earth. The whole character of the divining rod may be safely rested on the single experiment of blinding the diviner. Young or old, if guided solely by the divining rod, he could repeatedly trace the same courses blindfold, which he has before traced, always marking his veins and fountains of water in the same places, the rod would gain credit; but since he cannot, it must sink, -- it must be forsaken. The supposed laws of the divining rod are absurd. It goes blindfold when the diviner is blindfolded; and the cherry, the peach, and the hazel itself, are excelled in the subtilty of their divining motions by dry and nervous whalebone. The pretensions of diviners are worthless. The art of finding fountains and minerals with a succulent twig, is a cheat upon those who practice it, an offence to reason and to common sense; an art abhorrent to the laws of nature, and deserving universal reprobation. Note 1: The reader should not assume that a review such as this one, published in a "scientific journal," would not have reached a popular readership. Indeed, the essentials of this very article were reprinted in various newspapers of that period -- for example, by the Sandusky Clarion in its issue of Dec. 2, 1826. Practitioners of water witching and mineral rod divination in those days needed to be aware of contemporary rational arguments against their special activities, and it is reasonable to assume that information such as that printed in the 1826 "Divining Rod" article had wide circulation. Note 2: Given the fact that Silliman's Journal attempted to provide truly scientific reporting, it is strange that even its skeptical reporter was so unfamiliar with geology and hydrology. In instances where permeable underground rock strata are ubiquitous (as is often the case), there are no underground streams or fountains. The scientific basis for mineral rods locating underground "slippery treasures," (that move about of their own accord), is -- of course -- nonexistent. |

from: Quarterly Review (London) -- March, 1820 -- Art. III. -- Popular Mythology of the Middle Ages. [348-49] Art. III. -- 1. Dictionnaire Infernal; ou Rechcrches et Anecdotes sur les Demons, les Esprits, les Fantomes, les Spectres, les Revenans, les Loup-garoux, les Possedes, les Sorciers, les Sabbats, les Magiciens, les Salamandres, les Sylphes, les Gnomes, les Visions, les Songes, les Prodiges, les Charmes, les Malefices, les Secrets merveileux, les Talismans, &c. &c. &c. Par J. A. S. Colin de Plancy. 2 vols. Paris, 1818. 2. Histoire de la Magie en France depuis le commencement de la Monarchie, jusqu a nos Jours. Par M. Jules Garinet. Paris. 1819. 3. Danske Folkesagn, samlede af J. M.Thiele. Copenhagen. 1818. 4. Deutsche Sagen, herausgegeben von den Brudern Grimm. 2 vols. Berlin. 1816ó18. 5. Des Deutschen Mittelalters, Volksglauben vnd Heroensagen, von L. F. von Dobeneck. Berlin. 1815. 6. Tales of the Dead, principally Translated from the French. Tales of supernatural agency are not read to full advantage except in the authors by whom they are first recorded. When treated by moderns, much of their original character must necessarily evaporate; like tombs, which lose their venerable sanctity when removed from the aisles of a cathedral, and exposed in a museum. We reason where the writers of former days believed, and the attention of the reader is riveted by the earnestness of their credulity. Besides which, the very outward appearance of their volumes diffuses a quiet charm.... [365] ...Mining countries have often become the strong hold of popular mythology. Cornwall may be instanced; and thus also the Harzwald in Hanover, the remnant of the Hercynian forest, is entirely enchanted ground. 'In this district,' says an old author, 'are more than an hundred and ten capital mines, some of which have small ones belonging to them; some are worked for the king of Great Britain (as Elector of Hanover) on his own account, and the rest farmed out. According to ancient chronicles King Ilsung held his court at Weringerode in this forest, about the time of Gideon, judge of Israel, and Ilsung was the son of King Laurin the dwarfish monarch and guardian of the garden of roses, who flourished in the time of Ehud, judge of Israel, in the year of the world 2550.' -- These dates have been ascertained by the diligent chroniclers of the uncritical ages, who took great pains to force ancient fables into synchronism with the facts recorded by authentic historians. In the existing text of the Book of Heroes the Hercynian forest is not assigned to the sway of Laurin; but the chroniclers were probably also guided by local traditions, and even now the dwarfs and cobolds (spirits of the mine) still swarm in every cavern. Malignity is constantly ascribed to the goblins of the mine. We are told by the sage demonologist quoted by Reginald Scott, 'that they do exceedingly envy man's benefit in the discovery of hidden treasure, ever haunting such places where money is concealed, and diffusing malevolent and poisonous influences to blast the lives and limbs of those that dare attempt the discovery thereof. -- Peters of Devonshire with his confederates, who, by conjuration, attempted to dig for such defended treasures, was crumbled to atoms as it were, being reduced to ashes with his confederates in the twinkling of an eye.' Peters of Devonshire sought his fate. But the Demons who [366] haunted mines were considered as most tremendous. 'The nature of such is very violent; they do often slay whole companies of labourers, they do sometimes send inundations that destroy both the mines and miners, they bring noxious and malignant vapours to stitle the laborious workmen; briefly their whole delight and faculty consists in killing, tormenting and crushing men who seek such treasures. Such was Annabergius, a most virulent animal that utterly confounded the undertakings of those that laboured in the richest silver mine in Germany called Corona Rosacea. He would often shew himself in the likeness of a he-goat, with golden horns, pushing down the workmen with great violence, sometimes like a horse breathing pestilence and flames from his nostrils. At other times he represented a monk in all his pontificals, flouting at their labour and treating all their actions with scorn and indignation, till by his daily and continual molestation he gave them no further ability of perseverance.' ... [373] ...The Norman peasants believe that there is a flower which is called the herbe maudite -- he who treads upon it continues walking round and round, imagining that he is proceeding onwards, though in fact he quits not the spot to which the magic root has bound him. This spell seems to bind us; for we find ourselves still in company with the goblins of the mine, whom we imagined we had left far behind us. The Emperor is, undoubtedly, to be identified with those capricious powers. In the middle ages the winning of these riches became the trade of those sages who are the prototypes of the Dousterswivel of our northern enchanter, and the employment of treasure-finding was a regular profession in the mining countries, where some traces of it still remain. Each of these adepts had his own mode of operating. One was the Theurgist; he prayed and fasted till the dream came upon him. He was a pious man, and his art was holy; and if the eager disciple sinned against faith or chastity, the inspiration fled, the treasure vanished. Guilt, guilt, my son! give't the right name: no marvelThe natural magician smiled at the mystical devotee, whom he affected to treat either as the dupe of his own enthusiasm, or as an impostor. Trusting only to the secret powers of nature, he paced along with the divining rod of hazel * which turns in obedience, __________ * The employment of the divining rod when employed to discover ore or metal, was associated with many superstitions observances. The fact, however, of the discovery of water being effected by it when held in the hands of certain persons seems indubitable. The following narrative, which has been lately communicated to us by a friend residing in Norfolk, puts the subject in the clearest point of view. And we shall simply state that the parties, whose names are well known to many of our readers, are utterly incapable cither of deceiving others, or of being deceived themselves. 'January 21st, 1818. -- It is just fifty years since Lady N.'s attention was first called to this subject; she was then sixteen years old, and was on a visit with her family at a chateau in Provence, the owner of which wanted to find a spring to supply his house, and for that purpose had sent for a peasant, who could do so with a twig. The English party ridiculed the idea, but still agreed to accompany the man, who, after walking some [374] attracted by the effluvia from the metals concealed beneath the soil. These are delusions, thought a bolder sage who had been instructed in the secrets of Cornelius Agrippa: and he opened the sealed book which taught him to charm the mirror, in which were seen all things, however distant or hidden from mortal view, and he buried it by the side of the cross-road, where the carcass of the murderer was wasting on the wheel, or he opened the newly made grave and caused the eyes of the troubled corpse to shed their glare upon the surface of the polished chrystal. Telesms and pentacles, and constellated idols also lent their aid. Such were the implements of art belonging to an Italian or Spanish Cahalist. -- We give the story as it was related to us many years ago by a right learned adept. -- This Cabalist ascertained that if he could procure a certain golden medal, to be worked into the shape of a winged man when the planets were in a proper aspect, the figure so formed would discover all secret treasures. After great pains, he was so fortunate as to obtain __________ some way, pronounced that he had arrived at the object of his search, and they accordingly dug and found him correct. -- He was quite an uneducated man, and could give no account of the faculty in htm or of the means which he employed, but many others, he said, could do the same. The English patty now tried for themselves, but all in vain, till it came to the turn of Lady N., when, to her amazement and alarm, she found that the same faculty was in her, as in the peasant, and on her return to England she often exerted it, though in studious concealment. She was afraid lest she should be ridiculed, or should, perhaps get the name of a witch, and in either case she thought that she should certainty never get a husband. Of late years her scruples began to wear away, and when Dr. Hutton published Ozanam's researches in 1803, where the effect of the divining rod is treated as absurd (vol. iv. p. 260-7.) she wrote a long letter to him, signed X. Y. Z., stating the facts which she knew. The Doctor answered it, begging further information; Lady N. wrote again, and he, in his second letter, requested the name of his correspondent: that Lady N. also gave. A few years afterwards she went, at Dr. Hutton's particular request, to see him at Woolwich, and she then shewed him the experiment, and discovered a spring in a field which he had lately bought near the New College, then building. This same field he has since sold to the College, and for a larger price in consequence of the spring. Lady N. this morning shewed the experiment to Lord G., Mr. S., and me, in the park at W. She took a thin, forked hazel twig, about 16 inches long, and held it bv the end, the joint pointing downwards. When she came to a place where water was under the ground, the twig immediately bent, and the motion was more or less rapid as she approached or withdrew from the spring. When just over it, the twig turned so quick as to snap, breaking near her fingers, which by pressing it were indented, and heated, and almost blistered; a degree of agitation was also visible in her face. When she first made the experiment, she says this agitation was great, and to this hour she cannot wholly divest herself of it, though it gradually decreases. She repeated the trial several times, in different parts of the park, and her statements were always accurate. Among those persons in England, who have the same faculty, she says she never knew it so strong in any as in Sir C. H. and Miss F. It is extraordinary that no effect is produced at a well or ditch, or where earth does not interpose between the twig and the water. The exercise of the faculty is independent of any volition.' So far our narrator, in whom, we repeat, the most implicit confidence may be placed. The faculty so inherent in certain persons is evidently the same with that of the Spanish Zakories, though the latter do not employ the hazel twig. [375] the talisman, which lie confided to a workman, who gradually hammered the metal into the astral form, using his tools only at those moments when the Master, consulting the Alfonsine tables, desired him to proceed. It happened that the smith was left alone with the statue when it was nearly finished, and a sudden thought, inspired by his good genius, induced him to give the last stroke to the magical image. His hand fell in the right ascension of the planets; the virtue was imparted, and the statue instantly leaped from the table, and fixed itself firmly on the floor. No effort of the goldsmith could remove it; but, as he guessed rightly of the true nature of the attractive influence, he dug up the pavement, under which he discovered an earthen vessel full of coin, which had been concealed by some former owner of the mansion. Who could be more rejoiced than our goldsmith? Destiny had gifted him with the means of becoming the master of all the secret treasures of the earth. He instantly resolved to appropriate the inestimable talisman to himself; and, to evade pursuit, he embarked in a ship which was then setting sail. The wind blew briskly and favourably, and in a short time they were out at sea; when the ship sailed over a treasure concealed in the caverns of the deep. The talisman obeyed its call: it sprang from the hand of its astonished owner, and, with all his hopes, was lost for ever beneath the waves. Wretchedness, disappointment, and delusion thus invariably conclude the mystic or legendary narrations, in which human avarice is represented as yearning after gold, and attempting to wrest it from heaven or from hell. If the gift is bestowed, it becomes a glittering curse; but oftener it is denied, and Fate tantalizes the eagerness of humanity. When the Arab searches the ruined temple, the chest of stone sinks lower and lower beneath the soil. The rocks fall in and bury the treasure just when his charm is about to take; if the cavern opens before the suffumigations of the sorcerer, the treasure vanishes from his grasp. The moral is as obvious as the source of the mythos, in which we again observe the varied sway of the good and of the evil.... Note: An excerpt from this article was published in the June 26, 1820 Vermont Intelligencer. |