unOFFICIAL JOSEPH SMITH HOME PAGE

The MOUNDS MYSTERY

Joseph Smith: (Illustrations & Photos) | (Maps & Images) | (NY Histories) | (Money Digging)

??? (18??) |

??? (18??) |

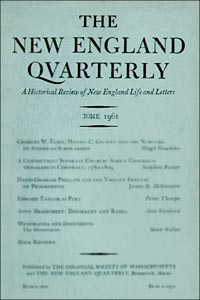

Dahl (1961) |

??? (18??) |

??? (18??) |

??? (18??) |

Captain Kidd | Treasure Seekers | American Israelites | Rods & Stones | Gold Diggers

(under construction)

(under construction)

(under construction)

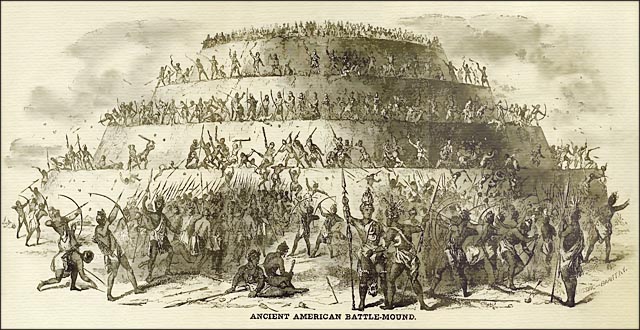

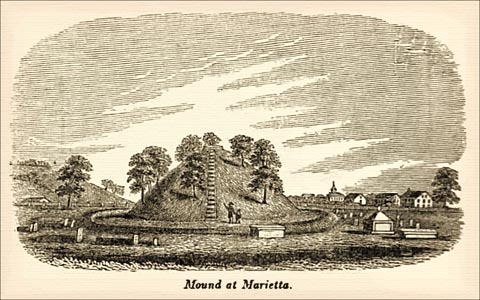

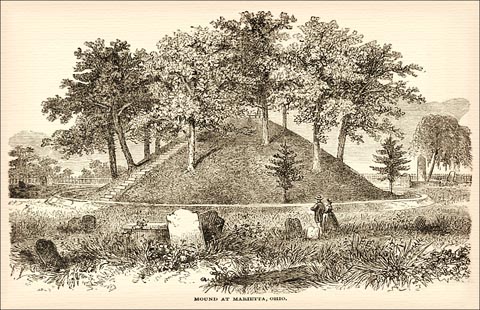

The New England Quarterly Vol. 34 #2 June 1961 [177] MOUND-BUILDERS, MORMONS, AND WILLIAM CULLEN BRYANT CURTIS DAHL IN the first few decades following the establishment of the United States as an independent nation considerable archaeological interest centered on the Mound-Builders. The Romantic love of the distant past, the desire to provide the new country with an antique and glorious history and the controversy over American natural history between nationalistic Americans and the followers of the French naturalist Buffon [1] prompted a number of archaeological books and articles, on these mysterious ancient inhabitants of America. These archaeological writings in turn between about 1800 and 1840 inspired a considerable series of poetic and fictional works. Here was antiquity rivaling or exceeding that of the Old World. Here were mighty ruins comparable to those of Egypt or Greece. Here was a tantalizing mystery to he solved and a whole civilization to be imaginatively recreated. Here was a tale of catastrophic annihilation offering splendid opportunity for pathos and moralizing. The story of the Mound-Builders was exactly suited to the literary taste of the period. It is no wonder that poets and novelists eagerly turned to it. Today these poetic and fictional accounts of the Mound Builders and their calamitous extermination seem impossibly romantic and dramatic. But in the early nineteenth century they did not. For these highly-colored literary works about the vanished race were only following with surprising closeness the most widely held scientific theories of the day. Indeed the archaeological writers themselves came so close to poetry and fiction that many of the poetic and fictional works now seem less fanciful than some of the supposedly scientific. --------------- [1] See Ralph N. Miller, "Nationalism in Bryant's 'The Prairies'," American Literature, XXI, 227-232 (May 1949). [178] I One of the best examples of an artistic treatment of the Mound Builders that is almost exactly parallel to early nineteenth-century archaeological theory is William Cullen Bryant's account of them in "The Prairies" and in "Thanatopsis." In lines 35-85 of "The Prairies" Bryant attributes the construction of "the mighty mounds" to a "populous race" that founded "swarming cities" on the prairies. The Mound-Builders he implies, were not red men, for it was the red men who massacred them. They were an agricultural people who used bison as draught animals. Their mounds were erected for three purposes: as tombs, as platforms for worship and as fortifications. This "disciplined" or civilized, race was beleaguered in its "strongholds" by "warlike and fierce" "roaming hunter-tribes" of red Indians who "butchered" them without mercy and caused their whole race to "vanish from the earth." Only a "solitary fugitive" was left at first "Lurking in marsh and forest" but later spared by the conquerors, to mourn in secret his exterminated people. Now the horsemen crossing the deserted prairies tramples with unconscious sacrilege on the dust of the multitudes of Mound-Builders. Similarly in lines 48-57 of "Thanatopsis" Bryant alludes to the many dead who lie beneath the soil of the American wilderness All that tread The globe are but a handful to the tribes That slumber in its bosom. -- Take the wings Of morning. pierce the Barcan wilderness Or lose thyself in the continuous woods Where rolls the Oregon and hears no sound, Save his own dashings -- yet the dead are there: And millions in those solitudes since first The flight of years began, have laid them down In their last sleep -- the dead reign there alone. These "millions " too are evidently Mound-Builders. [2] [2] This identification is most strongly supported by Bryant's emphasis on the great numbers of dead in American ground. See below. The sentiment, of course, [180] Almost every detail of this dramatic account is backed up by highly respected contemporary archeological works. [3] The archaeological writers, for instance, agree fully with Bryant on the populousness of America in ancient times. Jacob Bailey comments on how powerful, populous, and extensive the ancient American nations must have been. Benjamin Smith Barton asserts that they must have been "extremely numerous," while William Henry Harrison talks of their great cities and many villages. DeWitt Clinton writes of the "numerous nations" of the Mound-Builders and of the "vast population" of their towns. According to Caleb Atwater, the ancient population of America was numbered in the millions, and the banks of the American rivers were probably once "as thickly settled, and as well cultivated, as are now those of the Indus, the is common to Kirke-White, Porteous, Blair, and others (see William Cullen Bryant, II, "The Genesis of "The Genesis of Thanatopsis." New England Quarterly, XXI, June 1948, 163-184). In an early version the word "Barcan" in line 51 was altered to "Borean" (Tremaine McDowell, "Bryant's Practice in Composition and Revision," PMLA, LII, June 1937, 480-485). Bryant at this stage may have intended to make his poem wholly American. [3] The facts in this and the following three paragraphs are derived from Jacob Bailey's letter on the mounds to John Thornton Kirkland of Boston, Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society, iv (1795), 100-105; Benjamin Smith Barton's "Observations and Conjectures concerning Certain Articles which Were Taken out of the Ancient Tumulus... at Cincinnati," Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, iv (1799), 181-215; DeWitt Clinton's Discourse Delivered before the New York Historical Society at their Anniversary Meeting, 6th December, 1811 (New York, 1812. Also published in the Collections of the New York Historical Society II (1814), 37-98 and his Memoir on the Antiquities of the Western Part of the State of New York (Albany, 1818): Caleb Atwater's "Description of the Antiquities Discovered in the State of Ohio and Other Western States," Archaeolgia Americana: Transactions and Collections of the American Antiquarian Society, I (1820), 105-267; Samuel L. Mitchell's letters, ibid., 313-355: John V. N. Yates' and Joseph W. Moulton's History of the State of New-York, 1824-1826; Josiah Priest's American Antiquities and Discoveries in the West (2nd ed., Albany, 1833) William L. Stone's Life of Joseph Brandt -- Thayendanegea (2 vols, New York 1838) with its Indian legends of the mounds; William Henry Harrison's Discourse on the Aborigines of the Ohio (Boston, 1840. The address was delivered and first printed in 1838); John Delafield's An Inquiry into the Origin of the Antiquities of America (New York and London, 1839) and Alexander W. Bradford's American Antiquities and Researches into the Origin and History of the Red Race (New York, 1841). For a clear summary of early comments on the Mound Builders see Henry Clyde Shetrone, The Mound-Builders (New York, 1930), 5-22. In order to save space specific page references have been omitted. [181] Ganges, and the Burrampooter." From the "immense number" of skeletons discovered Atwater conjectures that "millions" were buried in the mounds. Alexander Bradford similarly stresses the "vast population," the "immense numbers," and the "astonishingly numerous" remains of the early Americans. "It is difficult, perhaps, to entertain," he says, "too exaggerated an idea of the immense population which once crowded this spacious territory." The vast public works, the ruins of great temples, and the remains of permanent cities prove that "great empires" once flourished in America. Josiah Priest and Yates and Moulton, however, are most like Bryant in emphasizing the numbers of the Mound-Builder dead. To the latter the mounds seem "monuments of buried nations" unsurpassed in magnitude and grandeur" in America. They mark where once stood cities containing hundreds of thousands of people. There are thousands of tumuli scattered all the way from New York to the Pacific. Kentucky, for instance, is full of the ghosts of a slain white race, and Ohio is "nothing but one vast cemetery of the beings of past ages." Priest believes that "ancient millions of mankind had their seats of empire in America." Many of the mounds are completely occupied with human skeletons, and millions of them must have been interred in these vast cemeteries, that can be traced from the Rocky Mountains, on the west, to the Allghenies on the east, and into the province of the Texas and New Mexico on the south: revolutions like those known in the old world, may have taken place here, and armies, equal to those of Cyrus, of Alexander the Great, or of Tamerlane the powerful, might have flourished their trumpets, and marched to battle, over these extensive plains. Who were these mysterious Mound-Builders? Several of the writers, such as Bailey, Bradford, Harrison, Atwater, and Samuel L. Mitchell, held that they were a more civilized group, of red men (or Malays or Tartars) -- perhaps the ancestors of the Aztecs or Mayas but not of the northern American Indians. They were slaughtered or driven out by tribes of their own race. But most of the serious archaeologists (and all the [182] crack-brained theorists [4]) concurred with Bryant in thinking that the Mound-Builders were not Indians at all but men of a different and now extinct race. John Delafield, for instance, thinks they were Cuthite Egyptians. Priest, after reviewing the evidence for their being antediluvians, Polynesians, Phoenicians, Egyptians, Greeks, Romans, Israelites, Scandinavians, Welsh, Scots, and Chinese, comes to the conclusion that at least they were white. On the basis of Indian legends Yates and Moulton also say that the mounds were fortifications built by whites who were exterminated by barbarous red men. Though,, like his fellow statesman Thomas Jefferson, [5] Clinton refuses definitely to identify the Mound-Builders, he too believes that they were different from the Indians. Bryant's conception that the Mound-Builders were agriculturists is supported by such authorities as Atwater, Bradford, Clinton, Priest, and Yates and Moulton. Though they differ over the precise degree of civilization attained by the ancient Americans -- some holding that it was exceedingly high, others that it was more nearly equal to that of the Mexicans or Peruvians at the time of the Spanish conquest -- all the archaeological writers concur with Bryant in the theory that the mounds represent a comparatively high culture catastrophically overwhelmed by barbarous hordes. The antiquity of some of the mounds, though not of all, is vouched for by all the writers. Bailey, for instance, suggests a date between 795 and 995 A. D. for the destruction of the Mound-Builders. Priest, patriotically trying to push American history back even before that of the Old World, argues that America was the country of Noah and ------ [4] For instance, John Ranking, Historical Researches on the Conquest of Peru, Mexico, Bogota, Natchez, and Salomeco, in the Thirteenth Century, by the Mongols, Accompanied by Elephants (London, 1827), and William Pidgeon, Traditions of De-coo-dah and Antiquarian Researches (New York, 1858 [copyrighted 1852]). Pidgeon believes reports of Greek inscriptions in Brazil, Roman coins in Missouri, Egyptian mummies in Kentucky, Phoenician letters in Massachusetts. and evidence of colonization by Persians, Hindus, Danes, Belgians, and Saxons. [5] In Notes on Virginia (1784-1785) (see Writings of Thomas Jefferson, Library Edition, ed. Andrew A. Lipscomb and Albert Ellery Bergh [20 vols., Washington. 1904], II, 131-141). [183] attributes some of the mounds to the antediluvians. Like Bryant he suggests a comparison with the ancient Greeks. All the writers accept the theory that at least some of the mounds were fortifications. All agree that some were tombs. And several, notably Harrison and Bradford, hold with Bryant that many were built as places of worship. Like Bryant, Atwater combines all three suggestions, but, again like Bryant, he emphasizes particularly that the mounds are the ruins of places of last resort where the Mound-Builders fought desperately to save their wives and children. In relation to "The Prairies," however, the most striking aspects of the archaeological writers' accounts of the Mound-Builders are the vivid and graphic imaginative descriptions of the final catastrophe that overtook the doomed race. Though instinct with terror and drama, the accounts by Clinton, Mitchell, and Delafield are general. These writers imagine the bloody extirpation of the Mound-Builders by floods of barbarians from the north of Asia. Fortifications (the mounds) stem the torrent for a time, but the defenders are eventually worn out and destroyed. Bradford's and William L. Stone's Indian legends make the scene more specific. According to them, in ancient times the Iroquois and other Indians conquered "a numerous and civilized people" "who lived in fortified towns." .After bloody wars, "the last fortification was attacked by four of the tribes, who were repulsed; but the Mohawks having been called in, their combined power was irresistible, the town was taken, and all the besieged destroyed." Harrison, setting the scene at a fort at Miami, Ohio, dramatically describes a last feeble band of the Mound-Builders in their ultimate stronghold making their final effort for country and gods before being exterminated by warfare in its most horrid form. Priest, too, is dramatic. He imagines the remnant of a tribe or nation, acquainted with the arts of excavation and defense; making a last struggle against the invasion of an overwhelming foe; where, it is likely, they were reduced by famine, and perished amid the yells of their enemies. [184] But not all the writers conceived of the extermination of every Mound-Builder; like Bryant some imagined the plight of survivors. Yates and Moulton, for instance, mention that after the cities had been stormed and taken a few survivors may have been able to flee through the forests, and Priest suggests that some (like Bryant's fugitive) may have hidden away, perhaps in vaults. It is Bailey, however, who most closely parallels Bryant's picture of the gory struggle and its aftermath for the few survivors, fierce, cruel, intrepid barbarians, driven by famine, burst, like an impetuous torrent, upon their polished and more effeminate neighbors, involving in destruction, all their monuments of industry, art, and refinement. If a spirited resistance is made, extirpation often becomes the consequence of a victory; and in case of a timid submission, the most humiliating and servile dependence ensues. The survivors of the "terror, havock, and desolation" become "slaves to savages" and are incorporated into their savage masters' tribes, or in "rugged climates and unsubdued wilds" they are obliged to labor so hard to subsist that they forget "every elegant and even useful improvement" with the result that their descendants become barbarians. II When the archaeological writers themselves were so imaginative and grandiloquent and dramatic, it is no wonder that Bryant's "The Prairies" and "Thanatopsis" were only two of a number of contemporary literary works based on the archaeological theories concerning the Mound-Builders. It is striking, moreover, how often the themes and situations already discussed in relation to Bryant's poems recur in the poems and tales by the other authors in this tradition of Mound-Builder literature. One of the earliest of these works is by the English poet Robert Southey. Inspired by a number of legends and a large body of literature purporting to prove ancient Welsh settlements [185] in America, [6] Madoc (1805) tells the adventures of an exiled Welsh prince and his followers who settle in North America, Christianize many of the natives, and war with the Aztecs, who then lived much farther north than they did when conquered by the Spaniards. Drawing largely on the stories of the Spanish conquest of Mexico but setting them back in the twelfth century, Southey fills his long poem with battles, abductions, human sacrifices, maidens in distress, hand-to-hand duels, young women dressed as boys, and the other usual paraphernalia of what may be called the "Aztec" novel. The mounds, he believes, are the remains of cities reared by Welsh and Aztecs before the Aztecs, defeated in battle, headed south toward Mexico. Another poet, Sarah J. Hale of New Hampshire, in her "The Genius of Oblivion" (1823) writes of the founding of the Mound-Builders' cities by fugitives from Tyre. [7] As in the evening a poetic young man named Ormond sits on one of the great mounds of the West and longs to know who built them, the Genius of Oblivion appears to him, and he hears a song about the countless millions of men of bygone empires who are now quenched in eternity. Suddenly he sees a vision of a splendid wedding in a gorgeous city -- Tyre -- but in the midst of the celebration the bride and the bridegroom flee in a ship because the tyrant king of the city suspects the bridegroom's loyalty and lusts for the bride. Like Longfellow's Norse couple in "The Skeleton in Armor," the lovers fly westward over the Atlantic and found a city in America. Mrs. Hale intended to ------ [6] See Southey's preface and notes. Compare Priest, op. cit., 226-228, 236-237, 337; Stone, op. cit., II 487-488; Yates and Moulton, op. cit., 45-57; and Samuel G. Drake, Biography and History of the Indians of North America (7th ed., Boston, (1837), 36-39, 110. [7] The Genius of Oblivion and Other Original Poems (Concord, N. H., 1823). Hale supports her Tyrian theory by notes to the Carthaginian voyager Hanno quoted by Diodorus Siculus. For similar theories that the Mound-Builders or Indians were Tyrians, Carthaginians, or Phoenicians see Priest, op. cit. Preface and 116; Drake, op. cit., and George Jones, History of Ancient America Anterior to the time of Columbus; Proving the Identity of the Aborigines with the Tyrians and Israelites; and the Introduction of Christianity into the Western Hemisphere by the Apostle St. Thomas (3rd ed., New York and London, 1843). [186] carry on her poem to tell of the destruction of the Mound Builders, but a hostile critical reception and a scarcity of babysitters prevented her. Even less skilfully written was the Rev. Solomon Spaulding's unfinished story Manuscript Found, probably written in 1808 or 1809 but never published by the author. [8] The story pretends to be a partial translation of twenty-eight rolls of elegant Roman writings on parchment discovered in an artificial cave covered by large flat stones on top of a mound, evidently an old fort, near Conneaut, Ohio. The carefully hidden rolls contain the story of a group of Christian Romans who in the time of Constantine while sailing for Britain are blown westward to America. [9] There amid "innumerable hordes" of savages they found a colony and hope to rear a new Italy. But driven by concern lest their children will degenerate into savages, they travel westward in the hope that they can return home in that direction. They soon come upon the great cities of the civilized Mound-Builders, who are taller and lighter than the other natives and who manufacture iron and lead, keep flocks and horses, domesticate mammoths, and have an extensive written literature. Spaulding goes on to reconstruct the cities, culture, society, polity, and lives of the Mound-Builders as he imagines them from the evidence of the mounds, and he tells the history of the two great Mound-Builder empires which during five hundred years of peace extended over much of the middle of ------- [8] The "Manuscript Found," or "Manuscript Story," of the Late Rev. Solomon Spaulding (Lamoni, lowa, 1885). Spaulding's story was published only alter it was asserted to be the true source of the Book of Mormon. Controversy raged over it. Though it contains striking parallels to the Book of Mormon, instead of attempting to prove it the source of Smith's book the critic can more profitably study both as outgrowths of a common tradition of writings about the Mound Builders. [9] Roman influence in Mexico was suggested as early as 1787 by Capt. Don Antonio del Rio (see Description of the Ruins of Ancient City, Discovered near Palenque, in the Kingdom of Guatemala, in Spanish America; translated from the Original Manuscript Report of Captain Don Antonio Del Rio... [London, 1822]) and was frequently cited by such writers as Priest and Pidgeon for another popular theory, that the mounds were built by the people of lost Atlantis, see particularly James H. McCulloh, Researches in America (Baltimore, 1816) and Researches, Philosophical and Antiquarian (Baltimore, 1829). [187] the continent. Finally, however, for a frivolous reason the two empires begin a deadly war of extermination, and though Spaulding's story breaks off before the end has come, one knows that the millions of Mound-Builders will kill each other off and leave only the remains of their fortified cities and the huge mounds heaped over their myriad dead. Under the American soil, Spaulding says, lie multitudes of the slain. Then he continues in much the same tone as Bryant: Gentle reader, tread lightly on the ashes of the venerable dead. Thou must know that this Country was once inhabited by great and powerful nations considerably civilized & skilled in the arts of war, & that on ground where thou now treadest many a bloody battle hath been fought, & heroes by thousands have been made to bite the dust. What happened to the noble Romans we never learn. Undoubtedly the most famous and certainly the most influential of all Mound-Builder literature is the Book of Mormon (1830). Whether one wishes to accept it as divinely inspired or as the work of Joseph Smith, it fits exactly into the tradition. Despite its pseudo-Biblical style and its general inchoateness, it is certainly the most imaginative and best sustained of the stories about the Mound-Builders. Its plot is too well known and too involved to require detailed repetition here. Shortly after the building of the Tower of Babel, one group of settlers from the Near East, the Jaredites, find their way from the Old World to the New and establish cities there. Because of their sins the Lord at length causes them to battle among themselves, and they are exterminated in a fierce seven-day battle near the hill Cumorah in Palmyra, New York. As their prophets had predicted, their homes become mere "heaps of earth upon the face of the land." The Jaredites leave behind them, however, golden tablets telling their history, which are found by the second and more important group of immigrants, the Nephites and the Lamanites. These are Israelites. [10] ----------- [10] For a discussion and bibliography of the exceedingly widely held belief that the Indians were descended from the Jews see Samuel Cole Williams' introduction [188] who have escaped from Jerusalem just before its destruction by Nebuchadnezzar in the time of Jeremiah (about 600 B.C.). Guided by God they have wandered in the desert, learnt how to build ships, crossed the ocean and settled in America the land of promise "choice among all other lands." In America they increase greatly till they number in the millions. They build great cities with huge fortifications. They become rich. They domesticate the native animals and till the land. But despite or because of their good fortune they experience the same religious and political problems that the United States was experiencing in Smith's own time. Even after Christ himself has come to America to teach his Gospel, time and time again groups of them fall off from the true faith and righteous living. Indeed, from the very beginning most of the Lamanites have been ungodly and have been given dark reddish skins as punishment (though Lamanites who are godly and join the Nephites can recover their light color). Through the centuries every backsliding group of Nephites joins the progressively more savage Lamanites. About 300 A.D., angered by the repeated apostacy of His chosen people the Lord determines to destroy the Mound-Builders' civilization. The few faithful Nephites war through many bloody years with the Lamanites and their allies. Once again the final and climactic battle (401 A.D.) takes place at the hill Cumorah. With a few exceptions the still civilized Nephites are exterminated by the savage Lamanites, the ancestors of the American Indians. In 421 A.D., however, just before he dies, Moroni, last of the Nephite scholars and priests, a solitary fugitive among the conquerors carefully buries the records of his people and an abridgment thereof in a stone box on top of the hill. There they were found centuries afterwards in 1827 by Joseph Smith by grace of visions sent by God. ----------- to James Adair, History of the American Indians (Johnson City. Tenn., 1930), xxix-xxx. Authors interested in the theory include Cotton Mather, Roger Williams, William Penn, and Jonathan Edwards and range in date from 1607 through the 1840's. The works by Adair, Elias Boudinot, Ethan Smith, and Israel Worsley are of particular interest. [189] Through the miraculous power of the Urim and Thummim, a pair of golden spectacles, Smith was able to translate the abridged Hebrew records written in ancient Egyptian characters and publish them to the world. On this book and on later revelations to Smith the Church of the Latter Day Saints is founded. Whatever one may think of the religious teachings of the Book of Mormon, or, one cannot deny that its often clumsy prose and disorganized narrative contain many vivid, exciting, and well plotted stories. A number of these are parallel to stories in the Bible, but others are tales of danger and battle and subterfuge and love that are both exciting and new. Joseph Smith, if he was the author, had the basic materials for a good historical novel. The last work on the Mound-Builders that demands mention here is Cornelius Mathews' Behemoth: A Legend of the Mound-Builders (1839)." Like the other authors, Mathews follows the archaeological writers in picturing America dotted with great cities of civilized Mound-Builders. In his story the terrified Mound-Builders are threatened with utter destruction by a supernaturally powerful mammoth named Behemoth. After several great armies have failed to slay the beast and the Mound-Builders' fortifications have proved ineffectual to restrain him, a great Mound-Builder hero named Bokulla finally pens in and kills the ravaging monster and preserves his compatriots. Mathews spends little space describing the civilization of the Mound-Builders, nor does he tell how they were finally exterminated. But as a member of the Young America group he is even more consciously nationalistic than Bryant in his effort to give America a legend and a tradition. Unlike his contemporaries Washington Irving, James Fenimore Cooper, and Nathaniel Hawthorne, he failed, for his frequently absurd book was quickly forgotten. Similarly, the Genius of Oblivion has gathered to her bosom the works of --------- [11] The Various Writings of Cornelius Mathews (New York, 1863), 89-115. See my "Moby Dick's Cousin Behemoth," American Literature, XXXI, 21-29 (March 1959). Melville shows interest in the Mound-Builders in the preface to John Marr and in Clarel (Pt. 1, Sect. xvii). [190] most of the other authors [12] of Mound-Builder literature with the exception of Joseph Smith, whose book (or transcription) has become famous for other reasons. Of the literary writings on the Mound-Builders, indeed, almost the only ones still remembered are "The Prairies" and "Thanatopsis." ------ [12] Because of its late date I omit from this study Daniel Pierce Thompson's "Centeola: or, The Maid of the Mounds,' published in his Centolia and Other Tales (New York, 1864) an exceedingly melodramatic story in the style of Robert Montgomery Bird or Edward Maturin about a young and beautiful Mound-Builder maiden and her lover who after terrible persecution from lustful and vengeful tyrants are saved from horrible death only by a catastrophic earthquake. Thompson assumes that the Mound-Builders had great cities; he believes them the ancestors of the Aztecs. The tone of the book seems almost incredible in 1864: one wonders whether it could not have been written early in the century but not published until then. =================== American Literature Vol. XXI #1 March 1959 [21] Moby Dick's Cousin Behemoth CURTIS DAHL Wheaton College AS PERRY MILLER has recently shown in The Raven and the Whale (New York, 1956), one of the most important members of the New York literary circle to which Evert A. Duyckinck introduced Melville about 1845 was Cornelius Mathews, then an exceedingly well known American man of letters. Melville and Mathews came to have many close contacts. [1] In 1839 Mathews had published a brief novel entitled Behemoth: A Legend of the Mound-Builders. [2] This supposedly terrifying tale concerns the struggle by an ancient American race to slay a gigantic mastodon surviving from past geologic ages. The ravaging Behemoth is finally hunted down and slain, after several disastrous attempts, by a doughty Mound-Builder hero named Bokulla. As Perry Miller has indicated, [3] there are striking parallels between this novel and Moby-Dick and especially between Behemoth and the Great White Whale. Behemoth is certainly Moby Dick's cousin; Bokulla is a distant relation of Ahab. [4] ------------ [1] Miller shows that Mathews was the leading figure in the Young America group with which Melville was for a considerable time associated and by whose ideals he was much influenced. See also Jay Leyda, The Meville Log (2 vols.; New York, 1951), 1, xxv, 250-253, 263, 366-367, 382-391, 397; and Eleanor Melville Metcalf, Herman Melville, Cycle and Epicycle (Cambridge, Mass., 1953), pp. 79-88. For Melville's articles in Mathews's humorous magazine Yankee Doodle see Luther S. Mansfield, "Melville's Comic Articles on Zachary Taylor," American Literature, IX, 411-418 (Jan., 1938). In the summer of 1850, while Melville was at work on Moby-Dicl<, Duyckinck and Mathews made an extended visit to him in the Berkshires. See Mansfield, "Glimpse" of Herman Melville's Life in Pittsfield, 1850-1851," ibid., pp. 26-36. [2] Reprinted in The Various Writings of Cornelius Mathews (New York, 1843), pp. 85-119. Melville had access to this edition. See Merton S. Sealts, Jr., "Melville's Reading: A Checklist of Books Owned and Borrowed," Harvard Library Bulletin, Ill, 408 (Autumn, 1949). References in parentheses in my text are to the 1863 reprint of this edition. Mathews was probably inspired in his conception of Behemoth by an Indian legend repeated in 1784 by Thomas Jefferson in his Notes on Virginia (ed. Paul Leicester Ford, Brooklyn, 1894, pp. 64-69, 78-79). The Behemoth of Job had been identified with the American mammoth in Adam Clarke's popular commentaries on the Bible (The Holy Bible with a Commentary and Critical Notes [by Adam Clarke], 8 vols.; London, 1810-1826, notes on Genesis 1:24 and Job 40:15-24). See also Josiah Priest, American Antiquities, and Discoveries in the West. ad ed. rev. (Albany, 1833), pp. 144-l50. [3] The Raven and the Whale, pp. 82-83. I regret that Miller's excellent study was not available to me when this article was conceived and written. [4] Though there seem to be no specific allusions to Mathews's novel in Moby-Dick. [22] Like Melville's Moby Dick, Mathews's Behemoth is immensely huge and powerful -- "the mightiest creature of the earth," whose progress is "unparalleled and majestic" (p. 108). His stature is "tremendous" (p. 97), his frame "monstrous" (p. 103) and "vast" (p. 97), his power "gigantic" (p. 108), his roar "like thunder near at hand" (p. 99), his tread "like the invasion of waters" (p. 99). When he advanced toward the terrified army of the Mound-Builders, his bulk dilated, till it came between them and heaven, and filled the whole circuit of the sky. The firmament seemed to rest upon his wide shoulders as a mantle... His face was like a vast countenance cut in stone,... with features large as those of the Egyptian sphinx (p. 102). His trunk is mighty and lithe and swift, "arteried with poison and death." His tusks are enormous and deadly. He shakes the earth as he marches, and yet his progress is incredibly swift. He is "a vast machine of war, containing in himself all the muniments and defences of a well-appointed host." (p. 102) More important, Behemoth (like Moby Dick) is, or seems at times to be, "a giant in instinct as well as in strength" (p. 99). His "huge and impenetrable frame" (p. 102) seems endowed with a corresponding "energy and stubbornness of purpose" (p. 97). To his brute strength is added "the cool and courageous sagacity of the leader" (p. 102). This intelligence is malicious, malign, "angry and barbaric" (p. 108). As in the case of Moby Dick, it shines out of his eyes: "Through his small and flaming orbs, his soul shot forth in flashes dark and desperate" (p. 102). Thus Behemoth is more than natural. Like Moby Dick, he seems immortal, invulnerable, ubiquitous, and perhaps divine. Decay cannot ---------- Melville does identify the mastodon with the sperm whale in terms that suggest Mathews's words: "that Himmalehan, salt-sea Mastodon, clothed with such portentousness of unconscious power, that his very panics are more to be dreaded than his most fearless and malicious assaults," "the mightiest animated mass that has survived the flood; most monstrous and most mountainous" (Chap. XIV). Mastodons are also referred to in the discussion of fossil whales in Chapter civ. The "ship's navel'' in Chapter xcix is probably also a reference to the Behemoth of Job 40:16. Compare the paralleling of whaling with behemoth-hunting in Mardi, Volume II, Chapter xvii. Though I have not specifically pointed out parallels in wording in Behemoth and Moby-Dick, in passages quoted from Mathews I have italicized expressions similar to Melville's. All italicizing in question is mine and for this purpose. [23] not touch him. He is the last of a race of gigantic antediluvian beasts destroyed except for himself in a geologic cataclysm. If not slain, the "unconquered brute," seemingly "unassailable and immortal" (p. 108), will endure for centuries, perhaps even beyond the duration of the human race (p. 97). He seems inescapable, "an almost perpetual presence" -- the spectral visitant of the nation; -- the monstrous and inexorable tyrant who, apparently gliding from the land of shadows, presented himself eternally to them, the destroyer of their race. He seemed, in these terrible incursions, to be fired with a mighty revenge for some unforgiven injury inflicted on his dead and extinct tribe by the human family. (pp. 95-96) His is "a power that seemed to overshadow the earth" and that at times rivals Deity, "more palpable in its manifestations, nearer in its visible strength, and less merciful in its might" than God's (p. 101). Yet he is in one sense devilish, "some monstrous prodigy, exhibited by the powers of the air or the powers of darkness, to astonish and awe" mankind (p. 91). Rational men, those who "drew their knowledge rather from the intellect than the feelings," believed Behemoth to be "the reappearance of a great brute, which, by its singular strength, in an age long past and dimly remembered, had wasted the fields of their fathers and made desolate their ancient dwellings" (p. 92). On the other hand, children ask if Behemoth is not the God they were taught to fear and worship. In the opinion of many even of the wisest, Behemoth is "the deity of the nation, who had chosen to assume this form as the most expressive of infinite power and terrific majesty" (p. 92). As Melville's mad Shaker prophet believes of Moby Dick, these men believe that Behemoth should be worshiped as a "national idol" (p. 113). It is this morally ambiguous, divine or devilish aspect of Behemoth that strikes almost supernatural panic into his foes. As in the case of Moby Dick, the terror he inspires is even more spiritual than physical. He appears to come between the Mound-Builders and heaven, to blot out the sky. The thought of his "vast and inexplicable power" seems to deepen the darkness around them and infuse "a portion of its weird influence into their souls" (p. 101). They feel utterly helpless before him. Their armies, paralyzed by fear, fly without striking a blow. Behemoth overwhelms their spirits; his "terrible shadow glided" into the national mind, and "no angle [24] of the wide realm of the Mound-builders escaped from the darkness of fear." Joy, ambition, love, and beauty dissolve "before the gloomy shadow of the general adversary" (p. 96). Even for Bokulla himself the hardest struggle is mental. For a long time, "tower as his thought might, it strove in vain to overtop the stature or master the bulk of Mastodon." "With this stupendous and inevitable image the whole might of Bokulla's soul wrestled" (p. 96). Yet this monstrous "image" is sometimes peaceful and calm when alone in nature. Like Melville's whales dallying in their nuptial chamber or peacefully reaping through vast prairie-like meadows of brit, Mathews's Behemoth plays innocently in the sea (he too swims). The giant beast seemed to be sporting with the ocean. For a moment he plunged into it, and swimrning out a league with his head and lithe proboscis reared above the waters, spouted forth a sea of clear, blue fluid toward the sky, ascending to the very cloud, which, returning, brightened into innumerable rainbows, large and small, and spanned the ocean. Again he cast his huge bulk along the main, and lay, island-like, floating in the soft middle sun, basking in its ray, and presenting, in the grandeur and vastness of his repose, a monumental image of Eternal Quiet. Bronze nor marble have ever been wrought into sculpture as grand and sublime as the motionless shape of that mighty Brute resting on the sea. (p. 102) [5] Even in this idyllic scene, however, Behemoth watches the Mound-Builders with an angry, fiery eye. This ironic collocation of peace and terror occurs ever more markedly in the description of the first battle between Behemoth and the Mound-Builders. Though men are cowering in fear, the day is sweet, calm, and cloudless -- seemingly "bright with beautiful auspices." "Save in the immediate path of the desolator, nature smiled, unalarmed and innocent in its primeval and virgin beauty." Nature seems to be trying to lure the Mound-Builders from their fierce purpose of destroying Behemoth even as in Moby-Dick it sometimes tempts Ahab to desist from his blasphemous pursuit of the whale. Green patches of forest, gentle slopes, rich meadows, and sweet wildflowers invite them to rest; babbling brooks murmur "reproaches on the warlike task they were ------- [5] Miller quotes this passage. In the comparison of whales to elephants in Chapter LXXXVI of Moby Dick, Melville comments particularly on the two animals' similar spouting. When emphasizing the peaceful aspect of the whale, Melville several, times mentions the rainbows formed by its spoutings. [25] at present pursuing." On high, the eagle and the vulture fly unalarmed uttering "shrill notes of ecstacy and rapture" (pp. 99-101). [6] As in Melville's novel also, the allegorizing is deepened by allusions to ancient myths. Behemoth is an idol, a "sublime image of stone," a bronze or marble statue. His face, like Moby Dick's, is likened to that of the Egyptian sphinx. He is something unholy that must be destroyed as Sodom and Gomorrah were destroyed. Bokulla, his destroyer, is compared to "the prophet and his chariot of fire" (p. 103). Of even more interest in connection with Moby Dick is the fact that Behemoth is the last of the Titans. A tradition still lingered among them [the Mound-Builders], that of that giant race, which had been swept from the earth by some fearful catastrophe, one still lived and might, from a remote and obscure lair, once more come forth, to shake the hills with his trampling, and with the shadow of his coming, darken the households of nations. Bokulla dreams of the "Titanic tribe of beings" "which had once tyrannized over the earth" (p. 92) and "of a conflict mightier than any his mortal eyes had ever witnessed..." "Armed beings of an inconceivable and superhuman stature passed and repassed before his mind... while in their midst one mighty Figure, neither of man nor of angel, stood chained, and, in a deep and fearful voice, cried to the heavens for succor" (p. 109). The valley in which Behemoth is finally entrapped was of old a prison of the Titans. Unfortunately, Mathews thoroughly confuses his reader by mixing his Greek myth with geology and paleontology. His Titans were mammoths, but whether they were destroyed by heroic men (Behemoth is revengeful against the human race), superhuman heroes or "angels," or a geologic cataclysm is never made clear. The allusion to suffering Prometheus seems to have no purpose at all There is none of Melville's skilful use of the heroic Titan as blasphemer yet symbol of the aspiring mind of man. II Though Bokulla is no Prometheus, the heroes of Melville and Mathews are in several respects parallel. Like the captain of the ------ [6] This peaceful aspect of nature is elsewhere symbolized by the mighty yet lovely black steed of the prairies, which is called the "silent, gentle, beautiful, the calm counter-image to Behemoth." (p. 110). Compare the mythical stallion mentioned in Moby-Dick, Chapter [26] Pequad, the mighty Mound-Builder is heroic primarily in the staunchness of his courage and the greatness of his thought. It is he who rallies his nation when it is paralyzed by fear. By the stunning defeat of the first battle, Bokulla (like Ahab immediately after the loss of his leg) is at first plunged into mental darkness and delusion (p. 97) but then stimulated to keener effort. With gleaming eyes and fast-clenched hands he single-mindedly takes up the challenge to hunt down and slay Behemoth as an "enterprise of magnitude and obstinacy sufficient to call up the whole soul of the man" (p. 105). Of necessity he becomes a solitary figure. His "heroic resolution, almost epic in its proportions and strength,... assuming to contend with unconquerable might" (p. 106), sets him apart from other men in "constant grandeur of soul" (p. 107). "Self-exiled and alone," like Ahab he ponders "long, and anxiously" over his first defeat and confesses that "he had formed but a vague opinion of the hugeness and strength of Behemoth when he had proposed the battle" (p. 106). Then he ventures bravely forth to pursue the mighty beast, "to behold the sum of his vast proportions" and to see "near at hand the actual dimensions of that shape whose shadowy outlines had" wrought "effects so boundless and disastrous" (p. 95). His passions kindled by the "shame of an inglorious defeat," he seeks "to discover, in the broad wilderness toward the sea, whatever means of triumph he might, over a power that had hitherto proved itself more than a match for human strength or cunning" (p. 106). Bokulla's quest is, of course, primarily a physical one -- to seek out and kill the great monster that has ravaged the cities of the Mound-Builders. But in Behemoth, as much more in Moby-Dick, the quest takes on broader, metaphysical overtones. Though the struggle may be fraught with fatal results to himself (in the end it is not), Bokulla will face the danger because he believes "that man must be triumphant, in the end, over this bestial domination" (p. 106). His self-trust has none of the blasphemy of Ahab's, but he too seeks to prove the preeminence of the human will. He has "a deep-founded confidence in the human character. Himself equipped with an indomitable will, and faculties stout and resolute as iron," he scorns the weaklings who would worship Behemoth and believes that by similar qualities of character "the nation was to be redeemed from thraldom." Man has survived cataclysmic geologic change, [27] the drowning of whole continents, and even the extinction of heavenly bodies. Bokulla refuses to believe that man has done so only "to be crushed at last by mere brutal enginery and corporal strength" (p. 96). Bokulla thus fights, as Ahab in the high and good sense of his quest also fights, for the dignity and safety, spiritual as well as physical, of mankind. "Touched by the sufferings and alarms of his nation," seeing them "pursued by a hideous phantom" "not only in the present time, but through a long futurity," he leaves his own home (his insular Tahiti) and, "launching himself in the boundless wilderness of the west," [7] facing solitude and doubt, determines to gain the knowledge that will save his people from their "terrible scourge" (p. 106). Erect in his chariot, like Ahab erect in his whaleboat, Bokulla goes out to face the foe. Like Ahab, he has something divinely grand about him. One of his officers remarks, "Bokulla hath the power and the knowledge of a God. Out of these men, but yesterday dumb and torpid with fear, he has struck the spirit of life, and that with the same ease as my sword-blade strikes from this dull stone at my foot, sparks of fire" (p. 99). Yet about him, as infinitely more about Ahab, there is a moral ambiguity. When haggard, wild, and spectre-like, he returns from his solitary reconnoitering, the people think him "a fiend of the prairie," "a lunatic," and "the keeper of Behemoth." Only later do they recognize him as "a saving angel" (p. 110). Like Ahab, he has a lofty, perhaps too lofty, pride. He "submits but poorly to the lording of any, be it man or brute." He repeatedly disregards the warnings of prophets. His spirit, as one of these comments, "pricks him on too far... He will not be stayed in his purpose" (p. 99). As a result he at first experiences defeat. In neither of the heroes, however, is pride a "gay buoyancy." "Even in the maddest onset and in the high flush of triumph" Bokulla's brow (like Ahab's) "was saddened, oftentimes with a passing cloud of gloom" (p. 94). III The two novels are parallel in other ways also. Both introduce the notion of fatality: Bokulla's first defeat is said to be "already ------ [7] For a description of the prairies closely resembling Melville's descriptions of the sea, cf. Behemoth, p. 101. Conversely, in Chapter cxiv of Moby-Dick Melville compares the sea to a prairie. [28] doomed in heaven" (p. 99). Both have long passages on preparing weapons for the struggle against the huge monster. In both novels the general mass of men alternate between fear of their supernatural antagonist and faith in the power of their leader. Both introduce humor, though Mathews's attempts in the dismally unfunny Kluckhatch scenes (Kluckhatch is a pigmy foil to Bokulla) are entirely unsuccessful. [8] Both novelists love turgid, rhetorical, inflated, often epic style. Both like aesthetically connotative words and make frequent allusions to Biblical and Classical myths even in consciously and patriotically American stories. Mathews, for instance, aims at Eastern richness when he says that Behemoth's tusks "curved and flashed in the sun like scimitars" (p. 102) and at Oriental mystery when he compares Behemoth to "a sublime image of stone in the middle of a silent lake" (p. 109) and to "a monumental image of Eternal Quiet" (p. 102). Both authors are influenced by the world of popular entertainment (the bones of mastodons and whales had long been exhibited in popular museums and traveling shows in the United States). [9] More significant is the similar technique of the two authors in building up physical mass and power and terror to such an extent that it becomes spiritually meaningful. Largely through their very size and mass and power, Behemoth and Moby Dick become devilish natural forces and come to represent that force of evil inherent in the nature of things to which, as Melville remarks, the Manichaeans ascribed dominion of half the world. Behemoth, for instance, though entirely an offspring of nature, is said to be like "the Spirit of Evil" (p. 99), and his voice "with its hollow peals" assaults "the very walls of heaven" (p. 102). IV But a discussion like this one of the parallels between Behemoth and Moby-Dick, however accurate and justified in its specific points, is necessarily misleading because it emphasizes only the similar aspects of the books. In truth, of course, despite their resemblances, the novels are very different. Though Mathews's best passages arc -------- [8] For a slashing contemporary attack on Mathews's humor, see William Gilmore Simms, "The Humorous in American and British Literature," a review of Mathews's Various Writings, in Views and Reviews in American Literature, Second Series (New York, 1845). pp. 142-184, especially pp. 149-150. [9] See Richard Chase's excellent comments on connections between Melville and P. T. Barnum in Herman Melville, A Critical Study (New York, 1949), pp. 81-82. The skeleton of a mammoth was one of the principal exhibits in Peale's Museum in Philadelphia. [29] surprisingly good and though he almost manages to exalt his melodramatic tale of terror into a spiritually significant struggle between man and a titanic -- perhaps devilish -- natural force, his book is hardly more than a long short story, while Melville's is an intricate, exhaustively planned, and artistically complete novel. Mathews has no live secondary characters; his allusions, unlike Melville's, do not really illuminate or expand a theme; his allegory is not consistent or worked out in detail. His suspense is suspense of action rather than of idea. And his ambiguities are merely incidental or even accidental; they do not lead to the profound questioning of reality and moral values that gives Moby-Dick its depth and intensity. His book has many of the trappings and externals of Melville's; it is in a similar tradition; and it seems to hint at similar meanings. But no part of it is really thought through. This, in essence, is the reason why, despite their similarities, Behemoth is a bad and often absurd book while Moby-Dick is a superlatively good one. |

return to the top of this page

The Joseph Smith Home Page