Bookshelf | Spalding Library | Mormon Classics | Newspapers | History Vault

|

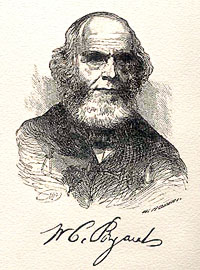

William Cullen Bryant (1794-1878) "Thanatopsis" North American Review (Vol. V No. XV, September 1817) |

|

|

|

Mormons, Mastodons & Mound-Builders | The Conneaut Giants | ||

|

Transcriber's Comments

In his 1961 article "Mound-Builders, Mormons, and William Cullen Bryant," literary critic Curtis Dahl quotes these verses from Bryant's "Thanatopsis: ... All that tread"These 'millions,' too, are evidently Mound Builders," says Dahl. He gives as his reason for this identification, that it is "most strongly supported by Bryant's emphasis on the great numbers of dead in American ground." Dahl also remarls on the differences between these verses in the 1817 original and in later editions, noting that "Bryant at this stage may have intended to make his poem wholly American." The critic is very likely correct in his reasoning on this point. William Cullen Bryant recreates the melancholy sentiments of these passages in his 1832 piece, "The Prairies," where his identification of the ancient American dead as the Mound-Builders is clearly spelled out. Both poems focus upon "the great tomb of man," though the later work more fully indulges in the Romantic poets' typical concern with the ancient past and the fate of "lost nations." Assuming the correctness of Dahl's interpretation, Bryant's writing of "Thanatopsis" marks the first mention of America's "lost civilization" in the poetry of her latecomer sons and daughters of European descent. "Thanatopsis" and "The Prairies" are among the poet's most highly acclaimed writings: both point the reader westward -- they are sunset poems and it is no coincidence that Bryant's friend, the artist Asher Durand depicts a late afternoon's fading light upon a practically deserted landscape in his mysterious 1850 painting "Scene from Thanatopsis." The death of the unknown past opens wide the early 19th century American frontier to both the hardy pioneer and the dreamy idealist. The "red men" of Bryant's "the Prairies" are thin upon the land, compared to the "millions" who once filled the continent. They are but a shadow of the "disciplined and populous race" who reared "the mighty mounds." Of course Bryant, like most of his contemporaries, got it all wrong -- the "red men" were the supposedly extinct "Mound-Builders." Perhaps a romantic poet could have picked up that truth and colored it with the literary shades of pleasurable remorse, but the effect worked better upon the reader if the living Indian tribes could be ignored and hazy images of noble civilizations, who "heaped, with long toil, the earth, while yet the Greek was... rearing on its rock the glittering Parthenon" presented in their stead. Bryant was a notable master of wordsmithing -- who used his verbal imagery to move the reader from one feeling to another, much like a composer carries along an audience in a moving stream of musical genius. Perhaps he was the first American poet to master this art -- at least he was one of the first writers recognized on the western shores of the Atlantic, as possessing these rare abilities. It is not surprising that he chose a Mound-Builder theme for some of his work, but it is, perhaps, regrettable that he never undertook to write the much needed epic of America's missing classical past. Mound-Builders and American Literature In summarizing William Cullen Bryant's contributions to a mythic view of the American past, Mr. Dahl offers the readers of his "Mound-Builders" article (published in The New England Quarterly XXXIV:2, June 1961) these insightful thoughts: One of the best examples of an artistic treatment of the Mound Builders that is almost exactly parallel to early nineteenth-century archaeological theory is William Cullen Bryant's account of them in "The Prairies" and in "Thanatopsis." In lines 35-85 of "The Prairies" Bryant attributes the construction of "the mighty mounds" to a "populous race" that founded "swarming cities" on the prairies. The Mound-Builders he implies, were not red men, for it was the red men who massacred them. They were an agricultural people who used bison as draught animals. Their mounds were erected for three purposes: as tombs, as platforms for worship and as fortifications. This "disciplined" or civilized, race was beleaguered in its "strongholds" by "warlike and fierce" "roaming hunter-tribes" of red Indians who "butchered" them without mercy and caused their whole race to "vanish from the earth." Only a "solitary fugitive" was left at first "Lurking in marsh and forest" but later spared by the conquerors, to mourn in secret his exterminated people. The modern connoisseur of early 19th century American Literature can only lament that a writer of Bryant's caliber did not undertake to compose a lengthier rendition of the "solitary fugitive" story. James Fenimore Cooper managed to fictionalize the story of the "last" of the Mohicans; Joseph Smith gave the world Coriantumr, last of the Jaredites and Moroni, last of the Nephites; but the American equivalent of a James MacPherson never arose to tell the Children of Columbia the epic narrative of the last of the Mound-Builders. Perhaps it is all for the best -- there were plenty of Delaware braves in America long after Chingachgook passed on to the heavenly hunting-grounds and the Mound-Builder blood still flows in the veins of native tribespeople today (albeit with no little or remembrance of their ancient glories). Had some Solomon Spalding of earlier years completed a vast saga of America's legendary past it would read probably today as uncomfortably as does Robert Southey's antiquated tale of Welsh warriors battling native Americans in pre-Columbian Aztlan. When the early investigators of America's hidden past got it into their fertile imaginations that great and powerful nations once inhabited the New World, they were soon forced to come up with some explanation of their demise. The fading of the southern Indian civilizations could be attributed to conquerors like Cortez, Pizzaro, and their ilk -- but what became of the supposedly pre-Indian, greay civilization of North America? Curtis Dahl relates the contributions of some of the leading early theorists in this speculation, men whom he uniformly calls "archaeological writers," though few of them would ever have qualified for a degree in that scientific discipline. He then adds: In relation to 'The Prairies,' however, the most striking aspects of the archaeological writers' accounts of the Mound-Builders are the vivid and graphic imaginative descriptions of the final catastrophe that overtook the doomed race. Though instinct with terror and drama, the accounts by Clinton, Mitchell, and Delafield are general. These writers imagine the bloody extirpation of the Mound-Builders by floods of barbarians from the north of Asia. Fortifications (the mounds) stem the torrent for a time, but the defenders are eventually worn out and destroyed. Bradford's and William L. Stone's Indian legends make the scene more specific. According to them, in ancient times the Iroquois and other Indians conquered 'a numerous and civilized people... who lived in fortified towns.' After bloody wars, 'the last fortification was attacked by four of the tribes, who were repulsed; but the Mohawks having been called in, their combined power was irresistible, the town was taken, and all the besieged destroyed.' Harrison, setting the scene at a fort at Miami, Ohio, dramatically describes a last feeble band of the Mound-Builders in their ultimate stronghold making their final effort for country and gods before being exterminated by warfare in its most horrid form. [Josiah] Priest, too, is dramatic. He imagines 'the remnant of a tribe or nation, acquainted with the arts of excavation and defense; making a last struggle against the invasion of an overwhelming foe; where, it is likely, they were reduced by famine, and perished amid the yells of their enemies.' Having placed William Cullen Bryant within a supposed literary stream which he calls a "tradition of writings about the Mound-Builders," Curtis Dahl goes on to demonstrate that Bryant was not the only American bard with the fate of the ancient people on his mind. The conceivable assemblage of such writers is, however, far too small to constitute a "tradition." By mid-century the identification of the builders of the prehistoric earthworks with the eastern tribes of North America was so complete that only the writers of admitted fantasy could satisfy an audience keen to hear the story of the mounds told in the old fashioned way. Dahl himself limits his choice of authors and poets to the first half of the nineteenth century, and he only manages to come up with a handful of them. His introduction to the second and third members of this select group is worth quoting at length: When the archaeological writers themselves were so imaginative and grandiloquent and dramatic, it is no wonder that Bryant's "The Prairies" and "Thanatopsis" were only two of a number of contemporary literary works based on the archaeological theories concerning the Mound-Builders. It is striking, moreover, how often the themes and situations already discussed in relation to Bryant's poems recur in the poems and tales by the other authors in this tradition of Mound-Builder literature. From Bryant to the Book of Mormon Robert Southey and Sarah J. Hale fit into Mr. Dahl's 1961 paper, along with William Cullen Bryant, rather comfortably. At least all three writers share a certain kind of overlap in some of the themes they chose to wax poetic upon, though their differences might easily be shown to outweigh whatever it was that have in common. Bryant and Southey were professional men of literature, well known and honored in their respective countries. Sarah Hale also became a woman of letters, though today she is probably remembered for little more than having written "Mary had a little lamb..." Only the dedicated student of long forgotten Mound-Builder lore would ever stumble upon her "Genius of Oblivion." Writer Dan Vogel, in seeking out possible connections between the mythic American prehistory and the origin of Mormonism, gave her footnote status in the sixth chapter of his 1986 book Indian Origins and the Book of Mormon. There he merely points out that Hale represented the views common to her day (that the builders of the mounds were "a different race than the Indians") and that she provided explanations wherein "she describes mounds and fortifications... mentions that some fortifications had 'pickets'... [and said] mound builders had metallurgy, including a knowledge of how to make steel." In all of these remarks Vogel is trying to illustrate the narrow tract of common thematic ground occupied by Mrs. Hale and the writer(s) of the Book of Mormon. He does not try to make a case for the latter volume having in any way been dependent upon Hale's 1823 poetic offering. In the same chapter Vogel notes that Bryant's "'Thanatopsis" is thought to be about the 'millions' of ancient mound builders who slumber in American mounds," but Vogel passes over the publication of the poet's "The Prairies" without a mention of its more substantial parallels with Book of Mormon themes. The problem being, of course, that the poem was not written until months after the Mormon book was published and therefore could not have influenced the thoughts of the book's supposed author, Joseph Smith, Jr. Instead, Vogel points out that Mrs. Hale, in a book she wrote in 1835, relates a story about a man's search for a hidden silver mine -- an activity obviously more typical of Joseph Smith the money-digger than of the writers who depicted the Mound-Builders in early American literature. Vogel was not the first student of the Indians to mention Sarah J. Hale and the Book of Mormon practically in the same breath, however. Robert Silverberg, in his 1970 book The Mound Builders, first talks about "The Genius of Oblivion," then devotes a few lines to discussing "A much more important New England poet, William Cullen Bryant," who "also fell under the spell of the mounds..." Silverberg's reporting offers no direct link between poets Hale and Bryant, but he associates their names with the writer of the Book of Mormon by juxtaposing them with the following words: One imaginative young man who was fond of reading and theorizing about the Mound Builders was a farm boy named Joseph Smith, born in Vermont in 1805. 'During our evening conversations,' Smith's mother wrote many years later, 'Joseph would occasionally give us some of the most amusing recitals that could be imagined. He would describe the ancient inhabitants of this continent, their dress, mode of traveling, and the animals upon which they rode; their cities, their buildings, with every particular; their mode of warfare; and also their religious worship. This he would do with as much ease, seemingly, as if he had spent his whole life with them.' What is important about Joseph Smith's fascination with the Mound Builders is that it led him to found a religious movement that is still very active in the United States: the Church of. Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, popularly known as the Mormon Church. Exactly who might have authored these purported "unpublished manuscripts of Mound Builder fables" here conjured up, Mr. Silverberg does not bother to say, but he leaves his readers with the impression that the "unpublished manuscripts" might have been the discarded output of a writer like William Cullen Bryant or Sarah J. Hale, both of whom first wrote and were published years before the Book of Mormon first went though the press in Palmyra, New York in 1830. Solomon Spalding The ideas and examples presented by Curtis Dahl in his 1961 paper predat Mr. Silverberg's very similar reporting by nearly a decade. Like Silverberg, Dahl does not confine his discussion simply to examining the content of a few sheets of early American poetry. Having exhausted his supply of poets fascinated with the mounds, Dahl has nowhere left to turn but to an examination of their prosaic contemporaries. He manages to find three of these -- actually, Dahl implicitly concedes that the number may only be two, depending on whether or not Solomon Spalding was the author of the Book of Mormon. The critic's words on this topic are: Even less skilfully written was the Rev. Solomon Spaulding's unfinished story, Manuscript Found, probably written in 1808 or 1809 but never published by the author. The story pretends to be a partial translation of twenty-eight rolls of elegant Roman writings on parchment discovered in an artificial cave covered by large flat stones on top of a mound, evidently an old fort, near Conneaut, Ohio. The carefully hidden rolls contain the story of a group of Christian Romans who in the time of Constantine while sailing for Britain are blown westward to America. There amid 'innumerable hordes' of savages they found a colony and hope to rear a new Italy. But driven by concern lest their children will degenerate into savages, they travel westward in the hope that they can return home in that direction. They soon come upon the great cities of the civilized Mound-Builders, who are taller and lighter than the other natives and who manufacture iron and lead, keep flocks and horses, domesticate mammoths, and have an extensive written literature. Spaulding goes on to reconstruct the cities, culture, society, polity, and lives of the Mound-Builders as he imagines them from the evidence of the mounds, and he tells the history of the two great Mound-Builder empires which during five hundred years of peace extended over much of the middle of the continent. Finally, however, for a frivolous reason the two empires begin a deadly war of extermination, and though Spaulding's story breaks off before the end has come, one knows that the millions of Mound-Builders will kill each other off and leave only the remains of their fortified cities and the huge mounds heaped over their myriad dead. Under the American soil, Spaulding says, lie multitudes of the slain. Then he continues in much the same tone as Bryant: 'Gentle reader, tread lightly on the ashes of the venerable dead. Thou must know that this Country was once inhabited by great and powerful nations considerably civilized & skilled in the arts of war, & that on ground where thou now treadest many a bloody battle hath been fought, & heroes by thousands have been made to bite the dust.' What happened to the noble Romans we never learn. Mr. Dahl's connection of the abandoned scribblings of would-be author Solomon Spalding with the polished verse of William Cullen Bryant is a most improbable one. The two men (one hesitates to call Spalding a "writer") share practically nothing in their respective styles and accomplishments. Perhaps Spalding's plea for modern man to "tread lightly on the ashes of the venerable dead" might be matched to Bryant's horse, trampling upon "the dead of other days," but the comparison is an odious one. There is little here to equate, other than the obvious fact that both Bryant and Spalding bought into the notions of their day and age, respecting the identity and fate of the Mound-Builders. The writer of the 1961 article passes along the sadly mistaken idea that the Spalding text he reports upon is the very same "Manuscript Found" cited by the old critics of Mormonism as being the true basis for the text of the Book of Mormon. Dahl can be forgiven in this misidentification -- after all, he is merely taking the RLDS Church leaders at their word when they say their 1885 publication of Solomon Spalding's "Oberlin manuscript" is that same noteworthy production. In fact, it is not, and in believing the RLDS claims Mr. Dahl strays slightly from the path to establishing a much more substantial connection for the extant writings of Solomon Spalding. In one of his notes the critic remarks: "Spaulding's story was published only after it was asserted to be the true source of the Book of Mormon. Controversy raged over it. Though it contains striking parallels to the Book of Mormon, instead of attempting to prove it the source of Smith's book the critic can more profitably study both as outgrowths of a common tradition of writings about the Mound Builders." More likely the "common tradition" meriting examination here is the one that links Spalding's story on file at Oberlin College, his long lost "Manuscript Found," and the very first draft of the Book of Mormon. But that is an investigation best conducted entirely aside from any consideration of the poems of William Cullen Bryant. As for "striking parallels," the Mormon apologists generally deny that the Oberlin manuscript contains any such thing. On the other hand, certain investigators have uncovered and reported scores of resemblances in theme and vocabulary, between the Mormon book and Spalding's known writings. Like Robert Silverberg (who may have plagiarized Mr. Dahl's 1961 article just a little) Curtis Dahl cannot resist the temptation of moving almost directly from faded visions of "unpublished manuscripts of Mound Builder fables" to the allegedly divine visions of Joseph Smith, Jr. He says: Undoubtedly the most famous and certainly the most influential of all Mound-Builder literature is the Book of Mormon (1830). Whether one wishes to accept it as divinely inspired or as the work of Joseph Smith, it fits exactly into the tradition. Despite its pseudo-Biblical style and its general inchoateness, it is certainly the most imaginative and best sustained of the stories about the Mound-Builders.... About 300 A.D., angered by the repeated apostacy of His chosen people the Lord determines to destroy the Mound-Builders' civilization... the final and climactic battle (401 A.D.) takes place at the hill Cumorah. With a few exceptions the still civilized Nephites are exterminated by the savage Lamanites, the ancestors of the American Indians. In 421 A.D., however, just before he dies, Moroni, last of the Nephite scholars and priests, a solitary fugitive among the conquerors carefully buries the records of his people... Back to William Cullen Bryant Curtis Dahl provides the name of one last candidate for admission to the Early American Writers' Mound-Builder Hall of Fame, and that is Cornelius Mathews. Strangely enough, an extended examination of Mathews' contribution to the demise of the "lost civilization" cause may eventually lead the reader back to the writings of Bryant. Here is what Dahl has to say: The last work on the Mound-Builders that demands mention here is Cornelius Mathews' Behemoth: A Legend of the Mound-Builders (1839). Like the other authors, Mathews follows the archaeological writers in picturing America dotted with great cities of civilized Mound-Builders. In his story the terrified Mound-Builders are threatened with utter destruction by a supernaturally powerful mammoth named Behemoth. After several great armies have failed to slay the beast and the Mound-Builders' fortifications have proved ineffectual to restrain him, a great Mound-Builder hero named Bokulla finally pens in and kills the ravaging monster and preserves his compatriots. Mathews spends little space describing the civilization of the Mound-Builders, nor does he tell how they were finally exterminated. But as a member of the Young America group he is even more consciously nationalistic than Bryant in his effort to give America a legend and a tradition. Unlike his contemporaries Washington Irving, James Fenimore Cooper, and Nathaniel Hawthorne, he failed, for his frequently absurd book was quickly forgotten. Similarly, the Genius of Oblivion has gathered to her bosom the works of most of the other authors of Mound-Builder literature with the exception of Joseph Smith, whose book (or transcription) has become famous for other reasons. Of the literary writings on the Mound-Builders, indeed, almost the only ones still remembered are "The Prairies" and "Thanatopsis." The tie between Mathews and Bryant is a subtle one, hinted at by Dahl only in a footnote, where he says. "See my "Moby Dick's Cousin Behemoth," American Literature, XXXI, 21-29 (March 1959)." An examination of this obscure and delightful article shows that, at least in part, Herman Melville was probably influenced by Mathews' "Behemoth" story in his writing of the American classic, Moby Dick. The possible lines of linkage between Bryant and Melville is a topic worthy of an extended dissertation, but it is unlikely that Behemoth: A Legend of the Mound-Builders would merit much of a mention in such a report. Robert Silverberg also devotes a few sentences to Mathews' 1839 novel, but avoids making any connection between it and Bryant's work. It seems evident (to the current writer at least) that some worthy comparing and contrasting of the dark themes of Bryant, Mathews and Melville might be a productive line of exploration for some aspiring graduate student of American literature. Each of these writers paid attention to the tragedies of death and destruction in uniquely American compositions, spiced with allusions to classical literature. Like Solomon Spalding, Mathews is a lumbering, unpolished, and oft times absurd story-teller, but his ideas merit a better consideration than a mere mention in listing writers of Mound-Builder fiction. Dahl has opened an interesting path to that end in his 1959 paper and it is not unlikely that a further exploration of that literary trail would cross the meanderings of William Cullen Bryant more than once or twice. And, to end on a whimsical note, one can only guess at what wonderous elaborations might have come out of the quaint notions of a Mathews or a Solomon Spalding, had they been picked up and fully developed by a Herman Melville or a William Cullen Bryant. |

Return to top of the page

Return to: Oliver Cowdery's Writings | Oliver Cowdery Home Page

last revised July 15, 2002