MAGAZINE ARTICLES FROM THE 1870s

PART TWO

1840s | 1850s | 1860s | 1870s (part one) | 1880s | 1890s | 1900s

Historical Mag. | Galaxy 1870-72 | Ladies Repository 1873 | Galaxy 1875

|

The Historical Magazine (NYC: American News. Co.) "Interview with Father Smith" "Birthplace of Joseph Smith" Transcriber's Comments |

|

|

HISTORICAL MAGAZINE. Vol. VIII. Nov., 1870. No. 11.

BIRTHPLACE AND EARLY RESIDENCE TO THE EDITOR OF THE TRANSCRIPT: -- The different authors who have given biographical notices of the above noted individual disagree in relation to the place of his nativity. Coolidge and Mansfield, in their History of New England, says that Joe Smith, the founder of Mormonism, was born and spent his youthful days in Sharon. Mr. Tucker, in his History of |

|

The Galaxy

Vols. 12, 14 (NYC: Sheldon & Co. 1870-1872) |

|

SAVED FROM THE MORMONS. I. I have been asked to write of my escape from a place and a people where the priceless gift of a good man's love for a woman in its wide, pure, spiritual sense, is unknown; its worthless, base counterfeit being a foul earthly passion on one side only, tainting and degrading its miserable object, body and soul. In my faulty, imperfect way, I will tell the story. My first recollection is of a lovely home in Lincolnshire, England. My father was a wealthy farmer, whose ancestors had owned Holthurst Grange since the days of good Queen Anne. Sweetness, cheerfulness, and a lithe, tender beauty express my dear mother, who was the daughter of the rector of the parish. God in His inscrutable wisdom saw fit to take her to Himself before she was world-weary, while life was yet full of hope and promise, while her children still sorely needed her. If she had been spared, this sorrowful history had never been written. As the tuberoses, which are so profusely laid upon the beloved dead in this country, bring sorrowful memories. so the scent of heliotrope and mignonette will ever be associated with my mother's dying hour. The sweet, heavy perfume of the pale purple and gray-green flowers growing beneath the window, filled the room, as, with difficulty folding me in her nerveless but loving arms, she drew me close to her breast, and gave to me, a girl of ten years, a solemn charge to watch over and protect Richard and Alice, my brother and sister, of seven and five. Young as I was, the sacred trust sank deep in my heart; and though I trembled and shuddered sorely, I gave my promise with sobbing earnestness, little wisting of the bitter years to come. For my poor father, who had loved his wife with an utter devotion, became a changed man after her death. The bluff heartiness of his manner, the stalwart erectness of his gait were gone forever. He was kind to us little ones in a sad, pitiful way, but scarcely ever noticed us. He ceased to take any interest in his farm, leaving all his affairs in the hands of his steward and servants. Before long everything fell into confusion, and at last a corroding fever stretched him upon his bed, from which he did not rise for many weeks. When he did, it was with a listless, weary, vague desire to go somewhere, anywhere out of his lost paradise. What wonder, then, that he should fall a victim to one of those emissaries of the Evil One, the "Latter-day Saints," who, with smooth, plausible manner and sophistical arguments, had sent so many heart-weary souls galloping on the road to hell? Yes, a Mormon demon invaded, haunted Holthurst Grange. He watched my father lynx-eyed; saw him trembling, hesitating; seized his opportunity, and bound him over body and soul to sell all he possessed and hasten at once to the paradise of saints, that unimaginable heaven upon earth, where troops of friends, abundance of this world's goods, and perfect bliss awaited him. Added to this was the solemn asseveration that the Mormons were the people whose God is the Lord Jehovah, who had secured for them on this earth a part of the rich inheritance which would be theirs in eternity. Yes, the fatherhood of God and the brotherhood of man in complete equality were the cornerstones of their faith; consequently envy, hatred, and malice were unfelt, unknown, in that land of pure delight. All this and much more was poured out with a bewildering eloquence which fell like dew upon the parched, hungry soul of my father. Not a word was breathed to him of the revolting feature whioh is the true Alpha and Omega. of the Mormon faith. The wily tempter reserved this bait for coarse and brutal natures. To my father the beautiful picture of a community of brothers touched him as nothing else could. If happiness were gone forever, surely there might be peace and rest; so under the gentle upspringing of this, as he thought, reasonable hope, he sold his long-descended inheritance, and taking us by the hand went resolutely away to the new and untried life. Hundreds of equally deceived and infatuated 678 SAVED FROM THE MORMONS. [Nov. persons made up the party; many of these were so miserably poor and degraded, and all so immeasurably inferior to my father, that I have since vainly wondered why the discovery of this fact did not give him a distrust of his newfound friends. Mormon hunting is the best ordered emigration society in the world ; for while they are glad to have well-to-do converts, they will also accept the very scum of the earth, who must pay "the church" by their subsequent labor for the expense of their transportation. I will not tire you with a description of the long, long journey which war before us, after we had reached and left New York. We received recruits at several points on the route, a motley crowd, gathered from all nations; some clattering about in wooden sabots or shoes, some barefooted, all lowly born and ignorant. Scores of children swarmed all over the huge wagons drawn by oxen, which were our only means of locomotion after we had reached the "Plains;" but I could find no congenial companion among them, and I clung only the more closely to my little brother and sister. Three poor little pilgrims were we, travelling, as we thought, over an endless, bewildering green desert, a vast billowy ocean of verdure and flowers, from which every night, miles and miles away, the sun seemed to go down a green and golden stair and pass through the very gates of heaven. When it grew dusk, and evening sank in the arms of night, the encampments, widespread upon the waste, with their flickering, uncanny night lights, kept us staid, prim little English children in a continual flutter of excitement. We encountered several tribes of Indians on our journey, to my extreme delight, immediately followed by excessive disappointment. I had read Cooper's novels, and Campbell's poem of "Gertrude of Wyoming," and you may imagine how naturally these feelings underwent such quick transition when I discovered, instead of the true nobility of nature, the almost divine heroism which these books had led me to expect, a set of thieving, tipsy savages, who with scowling visages demanded whiskey and yelled at the children. That I afterwards received from some of this debased race that help and succor which was denied me by my own people, indicates that true nobility might have been a common trait with them, before the enlightened white man demoralized the poor savage, body and soul. And so the days went lagging by -- till at last, sun-burned, weary, and dusty, we came to the end of our journey -- to Salt Lake City -- to home. Some of the elders visited our camp on the outskirts immediately; but after the customary salutation of "Peace be with you," they left us pretty much to ourselves. Father found great difficulty in obtaining any shelter, until he could decide what business he should pursue, and for some time we adhered to camp life. This was early in September. Before the cold weather set in, father bought some land a few miles from the city, upon which there were already some improvements, though sorry ones enough in our estimation. We had a cabin to cover us, built of logs filled in between the chinks with grass and earth. It was a mere hut, but our own; and father talked so cheerily of the nice house he would build in the spring, and the trees and flowers with which he would surround it, that we waited contented and hopeful. And now for months we were entirely alone. Although there were farms all around us, their occupants were either unsocial or too much engaged with their own affairs to attend to strangers. We also were very busy, for father and I developed the most brilliant faculty for turning the old boxes in which our goods had been packed into sofas, chairs, and bedsteads. Oh, I look back upon those days with a feeling akin to rapture! We loved each other; we were together, and alone! I know my father would have shuddered and recoiléd then, could he have foreseen the crooked ways in which he would afterwards walk; all the innate purity scorched out of his soul; his thoughts afraid, ashamed, ever again to dwell upon the dead wife he had so truly loved and lost. Early spring found us in a small house of four rooms which father had built, fiving his cabin to a hired man and his wife, Americans, who assisted him in the care of his stock, of which he now owned a quantity. These Americans were naturally intelligent and had some education, 1872.] SAVED FROM THE MORMONS. 679 and though they were beneath the class with which I had associated in England, I found in Mrs. Miller the friend and adviser I sorely needed. I was now in my fourteenth year. Like all English girls, I was more developed in person than an American girl of twenty. My hair was of a deep chestnut brown, and my hands of the same good rich color, owing to the chronic absence of gloves. My firm and by no means waspish waist held a healthy pair of lungs, to which I gave ample exercise, for I sang from morning till night. Singing was as natural to me as to a thrush. Chants, carols, and anthems sprang from my throat and heart as freely as the bird's morning and evening hymns were poured out in praise to their Maker. With all this, I was a most serious, thoughtful little woman, watching over my brother and sister with the love and solicitude of a mother. -- Up to this time, so secluded had been our lives. I had no idea. of the evil doctrines which governed the community in which we lived. Father attended the weekly meetings in the Tabernacle, but he very seldom took us children. I believe now that he shrank from exposing the vileness of their belief and practice to our innocent perceptions. Thus on Sundays I would have church at home. With my mother's prayer-book in my hand, standing opposite to Richard and Alice, I would reverently read through the beautiful English service of prayer, they responding with bent heads, in solemn tones. Then we would chant the glorious psalms and anthems, I leading, with soul uplifted, rising with the sound as the lark rises singing to heaven. We sang, not like the Sunday-school children I have since heard, boldly independent of time and tune, each squeaking to suit himself, but with perfect, harmonious accord; for we all had fine voices, and I was passionately fond of music. But too soon those pleasant Sundays came to an end. One dark day, dark to me though it was in the sweet month of June, Elder Pratt, the next in power to Governor Brigham Young, called upon my father, and, after conversing a little while on business matters, abruptly asked him, "Why do you not take a wife?" I started, and expected father at once to rebuke the impertinent question either by silence or an indirect reply. Hot tears came into my eyes at the thought of any one daring to take my mother's place. Imagine my dismay then when father quietly answered, "I have been thinking of the matter for some time, but do not know whom to ask." Then the two proceeded to the discussion of the women to be had, much as they would have spoken of the price, quantity, and quality of the cattle in the market. At last the Elder said, "Well, I think you had better take Eliza White and Ann Johns. They are both healthy young women, good workers, and will make useful wives." So intent were they upon the matter that they forgot my presence; but at this horrible speech I could endure no longer. Setting my teeth firmly and springing up, I exclaimed, with burning cheeks and flashing eyes, "What! marry two women? two women?" "Certainly, child; why not?" said the Elder, turning his cold gray eyes upon me. "Why not?" I repeated; "because no two good women would marry the same man!" Then a terrible thought crossed my mind, and I cried out, "Oh, do women do so in America?" Then sobbing, "But my father does not want two wives, nor one even to take my mother's --- " I could not go on; my sobs choked me. For a moment the men were silenced, and my father looked agitated; but at a sneering remark from the Elder he roughly bade me leave the room and not meddle with matters I did not understand. I obeyed, and ran quickly out to a little grove near the house. With a cry, "Oh, mother, mother!" I fell down in the grass, and poured out my tears and prayers. My poor little heart was raging against the bad man who was tempting my father to sin. In the midst of my anguish there came, descending from beyond the broad rustling green leaves high overhead, the scent of heliotrope and mignonette perfuming all the air, and I knew that my mother was looking piteously down out of heaven upon the poor little daughter who was weeping and calling upon her name. Suddenly the sweet, low voice of a woman singing camel dreamlike to my troubled senses, but the words I heard distinct and clear: 680 SAVED FROM THE MORMONS. [Nov. Christ leads us by no darker way, Then he passed through before; And who would in his kingdom come, Must enter through that door. Faint and fainter grew the sounds, as the singer passed on, but the blessed portent had done its work. I raised myself up and listened breathlessly for a moment, then "sobbed out: "Yes, mother darling -- I will try to bear this misery. I know my Saviour suffered; and he will help and comfort me." Then with slow, reluctant feet I returned to the house, and quietly went about performing my duties. A few days after this, as l was riding alone on a little pony my father had given to me, I met a sad-eyed woman whom I had often seen passing our house. Taking courage I approached her and said: "Will you tell me, do men have more than one wife at the same time in this country?" She regarded me with a pitiful look and returned: "Why do you ask, my child?" "Because I have no mother, and I have heard that which fills me with dread." And then she told me all about it -- how that she herself was one of four wives; that the three others and her husband all lived in one house. "Oh," I sighed, "are the women happy here? Do the women have more than one husband?" "Oh, no! Women have but one husband. Whether they are happy or not you will find out for yourself before long." Between that woman, Sarah Barnes, and myself there sprang up one of those strange friendships that sometimes exist between middle-aged women and children prematurely old. Looking back now, I know that her frequent counsels to be patient, to yield my opinions to circumstances, in addition to the example of her own patient, sorrowful life, greatly helped me to endure all those years of torture. One Sunday, soon after this conversation, a violent storm prevented father from going to the Tabernacle. I did not dare to commence our services; but little Alice, with the blessed innocence of childhood, climbed up to the shelf for the prayer-books, and after distributing them, placed herself demurely upon father's knee, saying with one of her rare sweet smiles: "Go on, Madge, we are ready; papa and I will read out of dear mamma's book." I did not look at him, but with a silent prayer for strength I read the opening sentence: "When the wicked man turneth away from his wickedness that he hath committed, and doeth that which is lawful and right, he shall save his soul alive." Father joined with us in the prayers and responses, his strong bass voice mingled with ours in the chants and hymns; while through it all, down deep in my heart, like a refrain, was a trembling supplication of my own that God would turn him aside from the wicked thing he contemplated doing, and send us happier days. All that day he was kind to us, more like his old self: and when once little Alice smoothed his face with her small soft hands, a big tear started from his eyes and rolled slowly down his cheek. But oh, with the morning came the Mormon elder -- the demoniac tempter, with his hateful counsel, which was little less than a command; and he never left us until a coarse, raw-boned woman was brought into the house, a great animal, against whom my heart rose in fierce rebellion -- refusing in her behalf to profane the sacred name of mother. She was my father's wife; and my friend Mrs. Miller besought me to hold my peace, and thank God that only one woman called my father husband. Alas! for that I had not long to thank Him. II. And now truly began our Mormon existence, and I ate thenceforth the bread of bitterness. With some remembrance of the decencies of life, father allowed Richard, Alice, and myself the use of one room. It was seldom invaded by Ann Johns, the new wife, and we came to regard it as sacred to ourselves. That was something; oh, it was a great deal to us. Most of the rough plodding work of the household was done by this woman, and I seized the unwonted leisure to educate my brother and sister. Among the treasures we brought from England was a lifesize portrait of my mother. I had never dared to ask father to unpack it and let us hang it upon the wall until that last happy Sunday, when, taking courage, with trembling lips I preferred my request. There was a few 1872.] SAVED FROM THE MORMONS. 681 moments troubled silence, and then it was granted. I am sure the hesitation arose from no unkind feeling, for the bit of canvas represented that which once held the whole heart and soul of the man. The thought of the outrage he was about to commit upon the memories of past happiness, pure and holy, unnerved him and made him dumb. I felt this, and quietly and quickly went out with Richard to get the precious picture. We hung it in our room in the best light, with our tears blinding us; for the sweet lovely features seemed to smile down upon us, and the beautiful eyes to follow us as if with a blessing wherever we moved. After this the poor place became glorified. When certain allotted daily tasks were done, we children were left to ourselves. Then Richard with Alice behind him on his pony, and I on mine, took long rides, exploring the country for miles around. In those little journeys I forgot the dark brooding pain which beset me in the polluted atmosphere of my home. Dear little Alice's bright face smiling and sunny, the pure air, and varied, beautiful scenery were like a psalm of consolation. The hours went smiling by, the gay deceitful hours; the lull before the storm. For before the summer was ended father commenced making preparations for building an addition to his house. At first I had no suspicion of his intention, but poor Ann, dull and stupid as she was, doubtless knew only too well what it meant. She suddenly lost her cheerfulness, and I often surprised her crying bitterly; little as I liked her, I was sorry, and pitied her with a vague compassion, asking no questions. It is but a homely tragedy, but when the addition was finished and father brought in Eliza White, and said she also was his wife, I stood confronting them for a moment, faint, dizzy, stupid with horror; then gasping for breath, I rushed past them into the open air. I walked; I ran until I fell down exhausted, with my mouth pressed against the earth to stifle my agonized cries, sobbing out my grief to that only mother left to me, the kind, merciful earth, in whose quiet breast our tortured bodies are laid when our souls go home to God. The eastern sky was glowing with the beams of the morning, and my clothing was drenched with dew, when with a painful effort I wearily raised myself to return to the house; but before I went, I registered a solemn vow to live as though the eyes of my sainted mother were ever upon me; to bear this indignity as she would have borne it; and more than all, never to stain may soul with the foulness of polygamy. From that day I talked to the children of the great evil of the land. I told them that I had the memory of our mother's pure life and earnest teaching to guide my steps; but they must remember my words, as I might not live to tell them of the terrible dangers which would beset them when they were grown. But oh, even then I felt most about Richard, and determined with God's help to devise some means of escape for him ere he reached manhood, lest he should be tempted to continue this foul wrong to women. In our long walks and rides, I would tell the children of all the cases of marked unkindness to wives; of those poor wretches who, no longer able to endure the throes of jealous agony, fled to the terrors of the wilderness and the savages, preferring them to the intolerable, unnatural tortures of their lives. Yes, I told my young brother and sister these shameful stories, until, though only half understanding, their faces blanched and they shrank in horror from the recital. What could I do? It was like setting a canker in a rosebud; it was poisoning, festering their healthy young souls. My own purity rebelled against it, and I could only pray that theirs with this cruel knowledge of evil would not be breathed upon beyond recall. My father's first wife, Ann, showed by her wan and spiritless demeanor that, coarse as she was, a woman's heart beat in her bosom; and Eliza, like many another Mormon bride, felt that her welcome was more hostile than hearty. Like Ann she neglected us children. She was a fat, sleepy-brained woman, who neither enjoyed nor suffered greatly. As I grew older I mixed more freely with the people of the country, partly from curiosity, but principally because father laid his commands upon me. I studied the women, and found that they were stolid, heavy-eyed, and indolent. The married women have pathetic faces, and fade young. With all the sophistry which is woven about them, they have 682 SAVED FROM THE MORMONS. [Nov. dreams of "the might have been;" of the joy that comes in its completeness to the heart that is all in all to one alone. Their cry goes up to God for divine love, but their unsatisfied hearts are doomed to be forever hungry for the love that is human. Oh, happy wives! who are sheltered in the sunshine of a good man's heart -- a heart which belongs to you, and you alone -- can you imagine anything more like the apples of Sodom than the Mormon marriages! I do not wish to give the impression that there were any highly-refined or cultivated women in Utah, for I do not remember one to whom an intelligent, superior man would turn for intellectual enjoyment; not one whom a poet might dream of, or an artist desire to paint. To a stranger they assume a joyful demeanor. This their religion not only inculcates, but enjoins to such an extent that no woman would dare carry a sad face intentionally, any more than she would parade a disgrace. No sad hymns or chants are tolerated; no one repeats a tale of misery to his neighbor on pain of Brother Brigham's displeasure. Their joys are frequently discussed, their sorrows never. The women in the same house (not home) are commanded to be-sister each other, and their tow-headed, all the way round to black-headed progeny tumble about promiscuously on the same grass-plot before the door. That they don't all go mad or kill each other is owing to what that powerful but ignorant sensual animal, Heber Kimball, called "triumph o' grace." The owner of all Mormondom is Brigham Young. He is the church. His will is law. If any one becomes obnoxious to him, that person receives a note advising him to leave. If he neglects this warning, the Destroying Angel will surely and speedily remove him. Young was born in Vermont, and at fifty years of age was a large, fine-looking man. Though uneducated -- for there was always an irrepressible conflict between his nouns and verbs -- his ability, diplomacy, and shrewdness are something marvellous. There is power in his eye of steely gray-blue; power in his massive chin; strength and power in the mouth shut so firmly. If he says No, that special petition is never renewed. His word is as the laws of the Medes and Persians. His system of tithing is worthy of the brain that originated it. When a man of property arrives, he must give an inventory of his possessions. Of these the church kindly consents to accept one-half, and afterwards one-tenth per annum, for which he receives a receipt from the Recording Angel. The only available road to the canyon which supplies firewood lies through Brigham Young's grounds. Families have the privilege of using this road, on condition that they leave every third load within the enclosure for church purposes. The Tabernacle is a long, low building of sun-dried bricks, 126 feet by 64. Its height is so disproportioned to its size as to give it a very squat appearance. it seats twenty-two hundred people on a pinch. The great temple, whose architectural plan was developed to Brigham by an angel, is hardly as yet above the foundations. When finished --if ever it is -- it will present an exceedingly comical mix-up of all schools and ages and styles, never seen before on earth, and let us hope unknown in heaven. The exhortations in the Tabernacle were of manifold complexion. Not the least curious was the gift of tongues, which consisted of the utterance of gibberish unintelligible to the speaker himself. One of the elders rose one day and gave us an address in what we were told was the Carthaginian language. The jargon would have disgraced a Hottentot. As to the misquoting of Scripture to suit their purposes, the Saints surpass the wildest imagining, and Heber Kimball overstepped them all. With permission I extract an exhortation by this brother, from Ludlow's "Heart of the Continent," as an example of tergiversation as ingenious as it is wicked: Seven women shall take a hold of one man. There! (with a resounding slap on the back of the nearest subject for regeneration) what d'ye think o that? Shall! Shall take a hold on him! That don't mean they shan't, does it? No! God's word means what it says, and therefore means no otherwise -- not in no way, shape, nor manner. Not in no way, for He saith, "I am the way, and the truth, and the life;" not in no shape, for a man beholdeth his nat'ral shape in a glass;" nor in no manner, for "he straightway forgetteth what manner of man he was." Seven women shall catch a hold on him. And ef they shall, then they will! For everything shall come to pass, and not one good word shall fall to the ground. You who try to explain the Scriptur' would make it fig'rative. But don't come to 1872.] SAVED FROM THE MORMONS. 683 ME with none o' yer spiritooalizers! Not one good word shall fall. Therelore seven shall not fall. And ef seven shall catch a hold on him -- and, as I jest proved, seven will catch a hold on him -- then seven ought; and in the latter day glory seven, yea, as our Lord said un-tew Peter, "Verily I say un-tew you, not seven but seventy times seven" -- these seventy times seven shall catch a hold and cleave. Blessed day! For the end shall be even as the beginning and seventy-fold more abundantly. Oh, the work of the Lord is ga-lo-rious! The cure by the laying on of hands is worthy the attention of wiser, more scientific people than those who practise it. I recollect an instance of a child seemingly dying who was restored to life by this means. A number of saints were sent for, selection those in the most perfect physical health and highest electric power. The little one was put into a warm bath, then taken out and wrapped in a heated blanket, beneath which the right hand of each saint in turn was inserted, and the child's body excited by vigorous rubbing. The electricity was conveyed in a perfectly continuous stream into the body of the child, and this was kept up for days, each one resigning his place to another on the least weariness, and the child was restored to health. So highly charged with electricity would these persons become, that showers of sparks would fly from their clothing when taken off; and one woman in perfect health and without a blemish of body, after rubbing the sick, by stepping hastily across the room could light a match with her finger, as readily as if it had been touched by a coal of fire. Try this remedy, parents, when your little ones are in danger of dying of weakness, after the disease has left them. If I could ever know that some little child of a Christian family had been saved from death by reading this part of my sad narrative, and then faithfully using the cure described, I should rejoice that this good at least had been evolved from the hated evils of my life. III. Years came, years passed -- dark, sad, cruel years -- until the harem of a civilized Christian gentleman -- as I once believed my father to be -- numbered five inmates, of many nationalities, and but little education or refinement, though some of the women could fairly lay claim to considerable beauty.I was now eighteen. I had learned much and suffered more, but as yet had not personally sounded the depths of Mormon degradation. I was not beautiful; only a well-developed, healthy English girl, with a bright, clear complexion and luxuriant hair; but I knew without vanity that I was fully equal if not superior in appearance to most of the women I met. That I was more intelligent is also true; for I read all the books I could obtain. I was passionately fond of music, a natural musician; for I could play upon stringed or keyed instruments intuitively, and my voice was true, sweet, and powerful. This talent I carefully concealed lest it should expose me to the notice of the speculating saints in women. Skilled musicians were rare in Brigham Young's dominions in those early times, and I well knew that if my talent were known my time would no longer be my own. Singing was the one joy of my life, yet I carefully abstained from it save when far away from human habitation. Then, with Rick and Alice, I would give full vent to my pent-up emotions. We were only three children as yet, and grand old times we had carolling in company with the birds. In our rides we made some strange friends with Indians, for we had a feeling that, though possessed of a darker skin, in some points their souls were whiter than those of our own people. About five miles from [Lake] Utah is the hot Spring, which flows from beneath a rock at the base of a mountain. The water is so hot that an egg may be boiled in it. This water, which commences in a stream the size of a man's body, spreads into a seething, steaming lake more than an acre in extent. The Utes and Arapahoes frequently met here, and on one of our visits we found encamped a band of Arapahoes. The chief came to meet me with a sad face, telling me in his broken English that his mother was very ill, and begging me to go in and see her. I found the poor old squaw ill indeed with consumption, that rarest of diseases in Utah. Nothing that I could do would prolong life, but I prepared jellies made from the wild fruits of the country, as my friend Mrs. Miller had taught me, and delicious soup from the game the hunters of the 684 SAVED FROM THE MORMONS. [Nov. tribe brought in. The poor feeble creature relished these delicacies more than anything her own people could make for her; my very presence soothed and comforted her. I would sit many an hour holding her brown, wrinkled hand in mine, singing and dreaming my dreams, pouring out my soul in the ballads and melodies I had learned in my childhood, the hymns I had been taught at my mother's knee, and the sublime chants of our beautiful church service. One after another the Indians would softly enter the wigwam, until Feotah the chief motioned them away. Then they would form groups outside, listening with bent heads, until I had finished the last note. They called me Wina Metre, or Singing-Bird; they looked upon me as inspired; not one of them but would have walked miles to do me the slightest service, and the old squaw would kiss my hand as though I were a goddess. One day Feotah told me that they must move, for their old enemies the Utes were on the war-path. He pressed upon me the gift of a pretty gray pony, to Rick he gave a beautiful bow and set of arrows, and to Alice a buffalo robe. To have refused these presents would have been a grave insult to their friendship. We saw them leave with genuine sorrow, for they had been true friends to us in our desolate condition. We had never been compelled to attend the meetings in the Tabernacle. The services were so repugnant that unless father desired us to accompany him we remained at home. But now Brigham Young himself ordered father to see that we attended regularly. From this command there was no escape. I knew that I had lately been kept under a strict espionage. I was mortally afraid of that mysterious horror the Destroying Angel, as the chief of the terrible Danites was called, and I went henceforth to the meetings with my brother and sister. But I charged them on the way to spend the hours at the Tabernacle in castle-building, in dreaming of anything, in sleeping, rather than to listen while the enormity of polygamy was speciously defended and smoothed over. This advice, which I also observed, brought my fate upon me. One Sunday the congregation commenced singing a hymn I dearly loved, because it had been taught me by my mother. Absorbed in dreams, the melody stole in upon my brain. Hungering after the lost happiness of my childhood, my full heart rose to my lips, and unconsciously poured forth its yearning in that hymn. High and higher rose my voice until it drowned the rest, and I came back to my senses to find all eyes fastened upon me, covering me with dismay and an undefined terror. The next day I was ordered by Brigham Young to become a member of the choir, which was largely composed of his own children, whose acquaintance I had no desire to make. I refused to go. Then I received a note signed by Fate himself, ordering me to be present at the next meeting of the choir. Resolved not to sing in that temple of Dagon, I braved my fate and stayed away. The following Wednesday, as I was sewing in my own room, my father opened the door and stood upon the threshold looking at me. There was that in his face which told me that a crisis in my life had arrived. He entered, and seating himself carefully, as I thought, with his back to my mother's portrait, he said, "I wish to talk to you upon a subject of great importance to us both." I bowed my head in silence, and waited for him to proceed, with a trembling heart and wistful look. But he became confused, and hesitated, and made some pointless observations about domestic matters. Then a dusky flush rose in his face; he frowned, and moved uneasily in his seat, and his breath for a moment came hard and fast. Oh, did a thought of my sainted mother arrest his cruel intention? did the wistful expression in my eyes remind him of her, and force the base proposition he was about to make back to his heart? But it came at last, his eyes not daring to meet mine; and shorn of the verbiage with which he strove to hide its loathsome features, it amounted to this: That I should at once become the eighth wife of Elder Pratt. I heard the bitter, shameful words. My breast heaved with my quick spasmodic breathing. Stung beyond endurance, I started up at last, and raising my hand as if I were registering an oath on high, I said, "Never," father, never, while God gives me life!" 1872.] SAVED FROM THE MORMONS. 685 "Do not say that," cried my father tempestuously, "for you only blaspheme. By to-morrow this time you will be the honored wife of a good man." I sank into my chair, and covering my face with my hands rocked my body to and fro with anguished moans. My suffering was too great for tears; the pain of those dry, choking sobs was intolerable. "No more of this nonsense!" urged my father roughly. "You have not liked your home, and you will have another cause of discontent when I tell you that to-morrow a daughter of Elder Pratt's will be sealed to me as a wife, while as the good Elder's wife you will have a home of which any woman might be proud." "Proud of the eighth part of a husband, the eighth part of a home! God forbid! I will not so degrade my womanhood! I will not so steep my soul in infamy! Oh, father, think of your promise to my dying mother; can you have the heart to consign me, her child, to a torment besides which death would be only too welcome? I cannot do this thing, I ---" "Hush, you jade! how dare you brave my authority? See to-morrow that you receive cheerfully, and marry without one word of dissent, the man who has honored you by his choice, or" -- and a wrathful flash shot from his eyes -- "you will rue the day you were born." As he spoke these cruel words, he rose and went hastily out of the room, leaving me trembling with rage and horror at the double abasement and outrage with which he had overwhelmed me. I was to bartered, traded away for one of the loathsome old man's daughters. My father had sold me, not because love for another had blinded his conscience, but from a base, sensual desire to increase the inmates of his harem; and I -- I was to enter into the same dishonored life -- all good impulses offended, all pure instincts outraged, to the end of my miserable days. Was there no escape? Escape! How the word rang through my half-crazed brain. With my hands pressed upon my burning, tearless eyes, I repeated this word over and over in my mind, until meaning fled. Ghastly faces floated in the air, the faces of the women who I knew were suffering the torments of the hell to which I was doomed. Suddenly I heard my darling little sisters voice calling to some of my father's other children in the playground below. The sweet voice and trilling laugh of the child, so ignorant of may misery, opened the flood-gates of my tears. Sinking upon the floor, and laying my head upon the chair, I wept unrestrainedly. From weeping I turned to praying. Soon the light came; my way was clear. I would escape from this moral grave that yawned before me, if I went knowingly to my physical death. I would literally "flee to the mountains." When night had come I hastily gathered together a few clothes, and then retired as usual, to avoid exciting suspicion. Little Alice cuddled close to me, asking sleepily, "What keeps you, dear Madge?" "God keeps me," I thought, as I kissed the flushed, warm cheek of the sleeping child. I told neither Alice nor Richard of the base proposition that had been made to me, nor of my determination to leave them, the only beings dear to me on earth. I thought if they knew nothing father would not revenge my disobedience upon their innocent heads. About eleven o'clock I rose from my bed, and kneeling down with a breaking heart, I commended my darling sister to the God of the helpless and desolate. I prayed that I might escape so as to make a way for her to leave this modern Sodom. My blithe, pretty, innocent sister! My tears fell on her face as I softly kissed her, and they rained down as I bent over Richard for a last look and blessing. His arm was curled round his head, his beautiful face was the picture of health and innocent happiness; yet as he grew how could honor and faith and respect for women blossom in that foul air? Oh, how I prayed that he might loathe and abhor the peculiar sin of this people! that in him God would raise up a reformer who would in some measure atone for the wrong-doing of our father, Kissing them, I stole softly out, and in another moment stood beneath the starry sky. I went to where my pony was fastened, gathered up the rope or lariat, saddled and bridled him, took my little sack of clothing and provisions, not forgetting a small pistol and ammunition and matches, strapped them all on with a heavy blanket, as soldiers carry their knapsacks, mounted him, and rode away into the night, a homeless, desolate girl. Of my escape I will tell next month. |

|

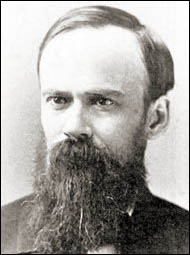

Truman H. Safford (1836-1901) "The Mormon Prophet" The Ladies Repository L:5 (Boston: Univ. Pub. Nov. 1873) |

|

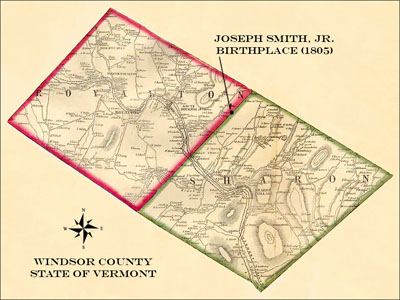

The Mormon Prophet. The annals of the world hardly present a more wonderful exhibition of ignorance and imposture, nor of willful fabrication, than was exhibited by that prince of charlatans, Joseph Smith Jr., the pretended Mormon prophet and revelator. Nor do the records of the human race furnish many such extraordinary and successful attempts as were made by this man to delude and defraud a credulous public. By the pretence that he was appointed by God a seer, revelator and prophet, that he had the power of salvation and damnation in his own hands, he gained an ascendancy over other men, inspired them, by an appeal to their fears, their interests and passions, with an attachment to his person, and caused them to acknowledge him both as a spiritual and temporal head, and assist him in obtaining proselytes in nearly all the different countries of the world. A great many years since there lived in the northeasterly portion of Royalton, Vt., very near the Sharon line, (the house in Royalton and the farm mostly in Sharon) a man by the name of Joseph Smith who married a woman named Lucy Mack. The father of this lady I well recollect. He used to ride about the country on horseback with a side-saddle. He was somewhat infirm, or had met with an accident that disabled him from labor, and he spent a portion of his time in peddling an autobiographical sketch of his own life. The Smith family consisted of the parents and nine children, the prophet or Joseph being the fourth in the order of age. Joseph Smith Sen., was a thriftless man and spent a portion of his time in hunting and fishing, other portions in digging for Captain Kidd's money, but his more profitable labor was in searching for hidden springs of water, and digging wells. The search for springs was made while holding in his hand a forked stick of the hamamelis virginica of the botanists, a tall shrub with yellow blossoms that flowers late in autumn, and is popularly called witch-hazel, as it was said to have been formerly used by the Lancashire witches. When Mr. Smith passed an underground spring of water he alleged that the forked ends of the shrub would spring down while in his hands and indicate with unerring certainty the presence of water, which only needed his keys, a shovel and spade, to bring it to the light. Joseph Smith Jr., was born in the house previously described, situated in Royalton, on the 13th of December, 1805. In 1812 the elder Smith with his family removed from this house to the Woodard neighborhood in Royalton, and Judge Woodard, now of South Royalton, writes me that he recollects that young Joseph, then a lad of seven or eight years of age, came to the raising of his father's house. Mr. Smith again removed to the Metcalf neighborhood, resided there for a season, and in the summer of 1816 he left Royalton with all his family, including Joseph the prophet, and settled in the town of Palmyra, New York, opened a cake and beer shop, and also pursued his old calling of hunting, fishing, making baskets, digging wells, etc. For a little more than two years he was a resident of that town, and then took a settler's possession of a piece of land in the neighboring town of Manchester. Joseph had the reputation of being the laziest and most thriftless of any of the Smiths at Palmyra, and was regarded as a cunning, [370] shrewd and unprincipled youth. He now occupied some of his time in reading, and was fond of sensation story books. He also attended revival meetings, and quoted texts from the Bible while engaged in conversation. In 1819, while Joseph Smith Sen., and his two eldest sons were engaged in digging a well, they found a singularly shaped stone resembling quartz mineral. Joe, as he was termed, was lounging around the premises, and took possession of this curiosity. He had now found what he designated a magic stone, and by its aid soon made wonderful discoveries. Hidden things, stolen money, lost treasure could now be readily recovered, and Joe adopted the profession of a money digger, and for a number of years he made dupes of all the credulous persons in the vicinity that he could influence by his marvelous stories to join him in this fruitless search. In 1827 there had been great numbers of excavations made by the Smith family and their dupes, but without any success in the discovery of treasures of any kind. Joseph now pretended that he had a vision, and that all the previous revelations in the world were false and that the true one was to be made to him; that he was to take from the earth a metallic book and translate it. With a spade and napkin he now repaired to the woods, and after a few hours absence returned with the Golden Bible and a huge pair of spectacles which he termed his Urim and Thummim. Smith pretended that the angel of the Lord directed him to translate this book, but he had colleagues, and by their aid a manuscript book was made by plagiarisms from the Bible and a manuscript novel written by Solomon Spaulding. Martin Harris was one of Smith's disciples, and a man of some means, and he took the manuscript home to examine and decide whether it would be safe for him to furnish Smith money to procure its publication. His wife, a person of superior judgment, committed it to the flames, and thus ended the first Book of Mormon. Another copy was made, and the book was finally printed by Mr. Grandin of Palmyra, N. Y. The Mormon Church was organized and the venerable Joseph Smith Sen., the witch-hazel well digger, was appointed patriarch and president, and his son, Joseph Smith Jr., was prophet, seer and revelator. Sidney Rigdon appeared as the first preacher of this new faith. In 1830, Kirtland, Ohio, near the residence of the two disciples, Rigdon and Pratt, was selected as the headquarters of Mormonism, and hither the president and patriarch removed, with his family, and a house was built for the prophet. Brigham Young was converted and joined them. Converts from other places now came in rapidly, and a part of the church removed to Independence, Missouri, but Prophet Smith remained for a season at Kirtland, superintending a "wild-cat" bank that he had established at that place, and looking after other property. But in 1838 the remaining Mormons mostly joined their brethren in Missouri, where fresh trouble awaited them; for they soon had conflicts with State authorities, mobs succeeded, and Joseph the prophet and his brother Hiram were capturered and lodged in jail. The matter was settled by an agreement between the Mormons and the State authorities, that the former should leave the State, and previous to the year 1840 they left for Nallvoo, on the Illinois side of the Mississippi river, which now became the headquarters of Mormonism. The Nauvoo house was built, a new city government organized, a temple commenced. Missionaries were sent to foreign countries to preach the Mormon doctrine, and returned with great numbers of converts. The Nauvoo Legion was trained and disciplined, and Joseph Smith Jr. appointed its commander. Says Mr. Tucker, from whom I quote: "The Nauvoo Legion, extending finally to an armed force of four thousand men with Smith as the general in command, was one of the fruits of State action. Smith, superbly equipped himself, had called to his aid a splendid staff, and at the last dress parade of the Legion he was accompanied to the field by a display of ten of his spiritual wives, dressed in a fine uniform, and mounted on elegant white horses." [371] General Smith was made Mayor of Nauvoo, and his property was estimated at over one million of dollars. But conflicts soon arose between General Smith and the authorities of Illinois, and the former with his brother Hiram led the Nauvoo Legion against Governor Ford; but an arrangement was finally made that the Legion should be disbanded, and that the Smiths and others of the leaders should be placed in jail and be protected until matters were settled, and then liberated. But an enraged mob broke into this place of refuge on the 27th of June, 1844, when the two Smiths were killed. The prophet was pierced by two balls and fell, calling in his dying moments on "the Lord, his God." Brigham Young, also a Vermonter, succeeded Smith as the head of the Mormon church, and for a long time after the death of the latter was more successful in gaining proselytes than Smith had been. But his fate may be as tragical as that of Smith.

T. H. Safford.

Truman Henry Safford (1836-1901) Professor Safford was born in the same Vermont county as was Joseph Smith, Jr. The Smith cabin strattled the line between Sharon and Royalton townships. When Royalton's notable historical figures are mentioned in books and articles, the two men generally share about the same measure of consideration. Safford was born a generation too late to have personally encountered the Joseph Smith, Sr. family in New England, so his reporting on that topic consists only of second hand information. For more details on the Smith family in Windsor County, Vermont, see the NYC Mormon of July 12, 1856, the Syracuse Sunday Herald of April 9, 1916 and Richard L. Anderson's 1971 book, Joseph Smith's New England Heritage. |

|

John Codman (1814-1900) "Through Utah" The Galaxy XX:3-6 (NYC: Sheldon & Co. Sept.-Dec. 1875) |

|

Transcriber's Comments

|

Back to top of this page

History Vault | Bookshelf | Spalding Library | Mormon Classics | Newspapers

HOME unOFFICIAL JOSEPH SMITH HOME PAGE CHRONOLOGY

last updated: Feb. 1, 2013