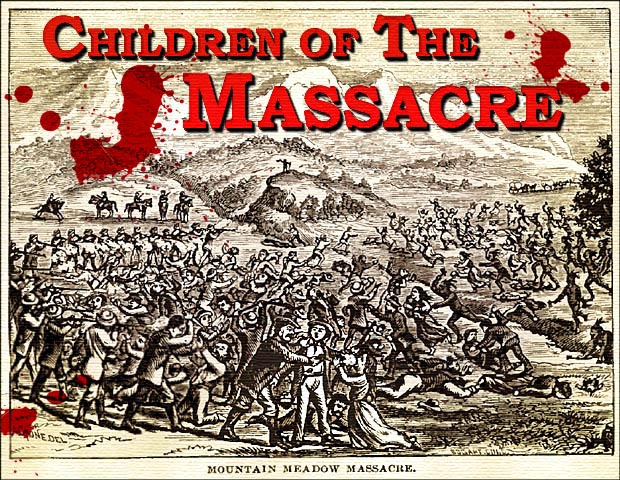

CHILDREN OF THE MASSACRE

SELECTED SOURCES ON THE SURVIVORS OF THE MASSACRE

AT MOUNTAIN MEADOWS, UTAH TERRITORY, SEPTEMBER, 1857

On-line Texts Page 1 | On-line Texts Page 2 | On-line Texts Page 3 | Idaho Bill | Links

This web-page: 1893 Post-Dispatch | 1940 American Weekly | 1941 True Stories

|

view images from original article: No. 1 | No. 2 | comments St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis, Missouri, July, 1893.

How J. P. Fancher of Berryville, Ark., Has Kept Track of the Surviving Children in His State, Missouri and Texas, Working for Government Aid Seeking to Bring About a Reunion -- Formation and Departure of the Emigrant Train -- Hostility of the Mormons -- Arrival at Mountain Meadows -- The Massacre, as Told in the Confession of Bishop Lee of the Mormon Church -- Servitude of Children Spared From the Slaughter -- Their Rescue and Return to Arkansas. This is the story of the greatest tragedy connected with the history of the State of Arkansas -- the Mountain Meadows massacre -- and of the strange afventures, rescue and after life of the few survivors of the great tragedy, the children of Arkansas parents. The latest effort in the direction of bringing about a reunion of these survivors of the Mountain Meadows massacre. Should this prove practicable, one of the most picturesque and pathetic spectacles possible would then be presented. Some point in the State of Arkansas will be chosen for the reunion, if it is found that the survivors of the Mountain Meadows massacre can again be brought together. It would be the first time they have met in a body since that day, many years ago, when, rescued from the Mormons and brought back to their native State, they were received by old neighbors, friends and kinfolk as though coming back from the dead. For more than a quarter of a century one man in Carroll County, Arkansas, has watched over the firtunes of these survivors of a historic tragedy with almost a fatherly interest. That man is James Polk Fancher, and the objects of his persistent care are the little remnant of that train of emigrants who escaped the bloody fate of their parents and friends at the Mountain Meadow massacre in the southern part of the Territory of Utah nearly forty years ago. The nephew of the brave commander of the train, and related to many other victims of the unparalleled butchery of more than 100 defenseless men, women and children, Mr. Fancher, the present County Clerk of Carroll County, has had good reason to exercise a kindly guardianship over that now scattered and diminished band of orphans whose infant eyes beheld one of the most terrific spectacles of inhumanity ever perpetuated in any land. "Polk" Fancher, as everybody in Carroll County calls the Berryville attorney and official, has never lost any of his zeal for the seventeen boys and girls spared by the Mormons and their Indian allies on that bloody day in September, 1857, when the Arkansas emigrants "surrendered" to John D. Lee and his trecherous associates after a week of fighting accompanied by horrors that to-day make the minds of thousands of people shudder when the Mountain Meadow massacre is mentioned. It was more than twenty-five years ago when Polk Fancher began to urge the claims of the survivors for Congressional aid. He thought the national Government should assume some parental care over the few persons who lost the dearest interests of life and every heritage of material wealth in that awful destruction of the train of emigrants. Many other prominent citizens of Nirthwest Arkansas have hoped that Congress would take some action in favor of the Mountain Meadow survivors. As the history [sic - historian?] of the great Mormon crime and the earnest and generous champion of the rights and interests of every survivor of the train, Polk Fancher has done more than any other person to keep alive the public sympathy in this matter. Related to Unoted States Senator James H. Berry and ex-Congressman Samuel W. Peel, both of whom were Carroll County men, Mr. Fancher has had some able workers in his cause at Washington City, but thus far no recognition of the claims of the survivors has been secured. With a view to the possible success of his laudable efforts to obtain some appropriation in favor of the Mountain Meadow people, the Clerk of Carroll County has through all these long years [kept] up a correspondence with most of the survivors, and the question of a reunion of the scattered remnant of the unfortunate train has often been contemplated, though the obstacles in the way of such a desirable event have so far prevented its achievement. But he has not despaired, and at the present time is renewing his efforts in this direction. The "Mountain Meadows Reunion" may yet be brought about in the near future. In the early spring of 1857, now a little more than thirty-eight years ago, a large and well-equipped train of emigrants left Northwest Arkansas for California. The counties of Carroll, Madison, Searcy, Marion and Crawford furnished the majority of the fortune-seekers, who were thus allured away from their quiet homes in the Ozark Mountains by the golden promises of the far-famed Eldorado of the Pacific Slope. The preparations for the momentous journey had begun long before the melting of the winter snows, and tradition says that all the country for many miles around Berryville, the county seat of Carroll County, knew of the contemplated adventure and talked much about the coming event. A trip across the plains then seemed a marvelous undertaking to the people of the White River region, who lived at least 500 miles from a railroad, and had but a vague idea of the nature of the outside world. So the approaching departure of these Arkansas argonauts naturally provoked a great deal of comment, for those were days when the pioneer settlers did not soon tire of a theme of local interest. The appetite of the mountaineers for news was fresh and vigorous. Books were few, and newspapers almost unknown in that rugged section of the Union, and the people discussed the current happenings of their territory of acquaintance when they met at house-raisings, log-rollings, shooting matches, camp meetings and other gatherings characteristic of pioneer life over a generation ago. Perhaps every man, woman and child in Carroll and the adjacent counties had heard about the prospective train weeks before the emigrants departed for the wonderland at the western end of the continent. When the emigrants assembled and organized for the trip they numbered about 140 souls, comprising over twenty families, most of these connected by various kindred ties. The heads of the families were yet in the prime of life. The men were stalwart pioneers of the East Tennessee type -- tall, muscular and resolute fellows -- trained in that rugged school of unconscious heroism that has given to the great West its forest-tamers and path-finders. The boys, just entering manhood, lacked the physical grace of the city youths of to-day who attend gymnasiums and participare in athletic contests, but the young mountaineers knew much about woodcraft, and in the arts of pioneer life they were very resourceful, in the use of the old flint-lock rifle, hammered out in a Tennesee forge years ago, these awkward lads seen about the camp of the emigrants were marvelous experts, and they looked forward to the prospect of drawing a bead on the big game of the plains as the most eventful feature of the journey. There were coy and modest maidens in the train, who had never been twenty miles from their mountain homes, and these fair young daughters of the Arkansas border looked westward with hearts full of romantic dreams as the train made ready to start on the long strange journey to the treasure-laden shores of the great ocean. About the camp fires little children frolicked and prattled, half wondering what the show of covered wagons, cattle, horses and people meant. There were forty wagons and a number of carriages in the train; about 1,000 head of cattle and several hundred horses. A magnificent stallion, worth $2,000, the finest animal, it was claimed, that ever crossed the plains up to that time, constituted a noble feature of the train. The value of the property which the emigrants took with them aggregated over $100,000. the old settlers of Northwest Arkansas to-day believe. It was an unusually rich company, and attracted attention everywhere along the way on this account. Capt. Alexander Fancher of Carroll County was the organizer and commander of the train. He had crossed the plaind twice before, and being a man of superior intelligence, integrity and courage, was well fitted for the leadership in the expedition which his followers by a unanimous choice assigned him. The commander was about 40 years old, tall and rather slender than heavy in body, his old neighbors say. He was a Tennessean by birth, had married in Cumberland County, Illinois, and settled on the Osage Creek in Carroll County, Arkansas, many years before the beginning of this story. Many relatives and friends came to the camp of rendezvous to tell the emigrants good-bye and wish them a safe journey. Tears dimmed hundreds of eyes at that memorable parting, and yet none in the weeping multitude dreamed that the separation would end all earthly relations between most of the members of that fated train and their kindred at home. Never did a company of brave adventurers turn their backs on loved ones and fond associations to march to a more terrible doom. The Fancher train, as it was called, moved out of Arkansas to the prairies of Kansas, taking the regular California route through that territory and Colorado. At every fort and station where letters could be mailed some of the emigrants wrote to the kindred and friends they had left behind. The news of the progress of the train was eagerly received at home, and through the local agencies for the distribution of this information thousands of people in Northern Arkansas and the border counties of Missouri knew all the incidents of the trip as they were told by mail from week to week. At all the camp-meetings, wool-pickings and quiltings held in Carroll County, Arkansas, during the summer of 1857 the latest report from the train was a preferred topic of conversation, and many letters written on the burning plains were actually worn out in passing from hand to hand among the numerous relatives and friends of the now distant reavelers. Letters came regularly till the train reached the southern part of Utah, The emigrants arrived at Salt Lake City late in August. Here they took what was known as the "Southern route," which ran through Provo, Nephi, Fillmore and Cedar City. At this time the Latter Day Saints were in a state of great excitement. The Unoted States mails had been stopped on Utah, a Governor had been appointed to supplant Brigham Young, who, in addition to his ecclesiastical sovereignty as President of the Mormon Church, was also the Chief Executive of the Territorial Government, and an army under the command of Albert Sidney Johnston was then marching toward Salt Lake City to see that the prophet and his followers did not longer defy the laws of Congress. It was an ill-fated time for the Arkansas emigrants to attempt to pass through the Territory, now so thoroughly dominated by the blind and zealous votaries of this un-American religious fanaticism. Never had the Mormon faith burned with more bigoted fervor than in the summer of 1857, when President Young issued his proclamation declaring war against the United States and commanding his followers, if necessary, to burn their homes, devastate the whole country around Salt Lake and flee, with what sustenance they could carry, to the mountain fastnesses and there defy the pursuit of the enemy. There is another fact of Mormon history which many persons have thought sheds some light on the events that will follow in the course of this story. Among the early teachers of the doctrine first promulgated by the prophet Joseph Smith was Parley P. Pratt, brother of Orson Pratt, whose zeal for the new faith would dare all opposition and danger. He was gifted with an eloquent tongue and something of a poetic fancy, it is said, and could urge the claims of the alleged golden plates and the mission of the Latter Day Saints as none of Smith's other co-laborers were able to do. Pratt went to Arkansas [sic - California?] on a proslyting tour, and while in that State converted the wife of a citizen of considerable prominence, who lived near Ft. Smith. The faithless wife went to Utah with Pratt and became one of the priest's household. In after years the woman returned with her Mormon husband to Arkansas. The injured husband now suspected that the woman was trying to steal away her children from their home and take them to Utah, so tradition says, and he chased Pratt out of the State, and after running him some distance into the Indian Territory overtook the fugitive and ended with a dirk the career of this Mormon evangelist. On this account, it is claimed, the people of Arkansas became peculiarly hateful to all loyal disciples of the Prophet of the Saints. Whether the fate of the Fancher train can in any way be connected with the killing of Pratt the writer will not attempt to say. The circumstance is given here as one of the many elements that make up the story of this tragedy. The train passed through Provo, Nephi, Filmore and Cedar City, and was about to leave the Great Utah Basin and cross over the summit of the cintinent to the Pacific slope, when all news from the emigrants suddenly stopped. Every mail for months had brought to the relatives in Arkansas letters from the moving train, but now there came an ominous silence. Weeks came and went, summer faded into autumn, the frosts of October were followed by the first harbingers of winter, and yet no word or trace of the lost train could be had. A thousand hearts in the mountain homes of Arkansas beat anxiously as the last days of the memorable year dragged heavily on and no tidings came of the missing ones. Doubts became fears, and fears grew into convictions of an awful calamity before the slightest clue of the mystery reached the friends of the vanished train. At last on the 31st day of December, 1857, William C. Mitchell, a memver of the Arkansas Legislature from Carroll County, received the first information of the massacre of the immigrants at Mountain Meadows in the southwestern part of Utah. Mr. Mitchell had obtained the news of the shocking butchery from Los Angeles, Cal., where the story of the massacre had been conveyed by other emigrants who passed through the meadows while signs of the crime were yet unmistakable. The Legislature of Arkansas at once took steps to investigate the affair, and so did the United States authorities. It was first reported as an Indian massacre, and a long time elapsed before the awful truth became known that Mormon hate treachery directed and abetted the savages in this almost unparalleled slaughter of 121 helpless men, women and children. Only the most convincing evidence could force such a revolting revelation on the public. That proof, however, came after Nemesis had seemed to sleep for years, and the details of the Mountain Meadows massacre were given to the world in the trial of the Mormon bishop, John D. Lee. On the 22nd of June, 1858, nine months after the massacre, Dr. Jacob Forney, United States Superintendent of Utah, discovered the whereabouts of some children supposed to be survivors of the Mountain Meadows tragedy. Up to that time it was not known by the relatives and friends of the Fancher train that a single soul had escaped death. The investigation went on so slowly, however, that another year elapsed before the children were gathered together. On the 15th of June, 1859, the following survivors of the massacre were placed in charge of Maj. Whiting of the Unoted States Army: Rebecca, Fannie and Sarah Dunlap, daughter[s] of Jesse Dunlap, deceased, from Carroll County, Ark.; Prudence. Angelina and Georgiana Dunlap, daughters of L. D. Dunlap, Marion County; Martha, Sarah and William T. Baker, heirs of G. W. Baker, Carroll County; Carson and Tryphenia Fancher, son and daughter of Capt. Alexander Fancher, commander of the train, Carroll County; John C. Mary and Joseph Miller, Crawford County; Milum and William Tackett, sons of Pleasant Tackett, Carroll County; Sophronia and F. M. Jones, children of J. M. Jones, Carroll County. When the children were found and rescued from the Mormons they had been in captivity nearly two years. The majority of the little orphans had no recollection of the massacre and supposed they were at home among those whose hands helped shed their kindred blood. A few of the older children remembered the awful scene of slaughter and the says of siege and fighting which preceded the final destruction of the train, but they were separated from the other survivors and had no means of telling their sad story to friendly ears. The children, except Milum Tackett and John C. Miller, were sent by Maj. Whiting to Fort Leavenworth, the two survivors named being detained in Utah as witnesses for the Government. At Fort Leavenworth the [----- band] of boys and girls stopped for a while until met by William C. Mitchell, special agent for the Government, and one Mrs. Railey of Arkansas, who took the survivors on to the homes of their relatives. Mr. Mitchell was the member of the Arkanasa Legislature who first heard of the massacre of the train. On the 16th of September, 1859, two years and four days after the Mountain Meadows horror, Mr. Mitchell and Mrs. Railey reached Carrollton, Carroll County, Ark., with their charge. Carrollton had been the home of many of the families that perished in the massacre, and it was here that most of the children were to be distributed among their relatives. The scene which characterized the reception of the surviving orphans at Carrollton is described by those who witnessed the event as one of the most affecting spectacles ever known and the old men and women who still tell the story seldom get through with the incidents without shedding tears. Some of the children were recognized by their relatives and claimed at once. Others could not be clearly identified, as they were so young. The survivors found homes among kindred or the friends of their parents, and each one of them became an object of especial interest to all the people of the surrounding country. The older children were talked to constantly for days about the massacre, and no doubt the little ones learned to believe some of the stories which fancy created where memory failed in trying to recall the details of the tragedy and its consequences. John C. Miller and Milum Tackett, the two witnesses, were taken to Washington City by Dr. Forney in January, 1860. After being examined by the government authorities the boys were taken to Carrollton, Ark., by Maj. John Henry of Van Buren. These children, though the oldest of the survivors, were too young to be used as legal witnesses and they did not testify in the trial of John D. Lee, which occurred after Tackett and Miller had grown to manhood. The full enormity of the crime of Mountain Meadows was not known till the details of the massacre were brought out in the trial of John D. Lee and his Mormon accomplices, and the confession of the only man who died to expiate the wholesale murder of the Fancher train paints this picture as one of the darkest combinations of cowardly treachery and fiendish barbarity ever held up to the view of a civilized people. At the time of the massacre of the Arkansas emigrants John D. Lee was living near the Mountain Meadows and acting as farmer for the Pah Utes Indians. Isaac C. Haight was President of the State [sic - stake?] of Zion and second in Mormon authority in Southern Utah to Colonel William. Dame, who commanded that military district. On or about Friday, Sept. 9, 1857, Capt. Fancher and his train reached the Mountain Meadows, eight miles siuth of the village of Pinto. This place was then a grassy valley about five miles long and one mile wide, walled in by high mountains. At either end of the pass was a good spring. West of this divide, which connects the Utah basin and the Pacific slope, lies what is known as the Ninety Miles Desert, and emigrant trains usually stopped here a few days to rest their stock and prepare for the journey across the waterless region beyond. Capt. Fancher, having traveled the route twice before, decided to stop at the Meadows and refresh his train. At the northern end of the valley or pass was the "corral" of Jacob Hamblin, sub-agent for the Pah Utes. It was at the southern spring that the Arkansas emigrants made their camp. The spring was in a gulch or ditch about eight feet deep. From the bank above the water the ground was nearly level for a distance of 200 yards, and on this part of the Meadows the wagons of the train were corralled. This must have seemed a pleasant camping place to the weary emigrants. They had now been on the road nearly five months and were about to cross over the great mountain range that divides the Father of Waters from the Pacific slope of the continent. Behind them were the memories of home and loved associations, while to the westward lay the goal of their new hopes. How these people, over whom the shadow of an impending doom was then gathering so darkly, spent the time from Friday till Monday morning will never be known. The oldest survivors of the train brought home with them only dim and shadowy memories of the stay at Mountain Meadows till the cruel scene of death began. Those days of rest were no doubt full of interest to the older emigrants. They talked of their old homes and wrote letters to relatives and friends -- letters that were destined never to enter the mails. The children played on the beautiful wild meadow and perhaps gazed in wonder at the towering mountains which walled in the little valley. Some of the men were perhaps busy repairing the harness of their teams, while the women washed and mended clothing and cooked a supply of food for the journey beyond the mountains. Thus, might fancy sketch, that the pen of the historian can never describe in musing on the last peaceful hours of the Arkansas emigrants who perished at the Mountain Meadows. At daylight on Monday morning, Sept. 12, while the emigrants were preparing breakfast, a volley of rifle shots startled the camp, and seven members of the train fell dead, while more than twice that number were wounded. The shots came from the gulch near the corral of wagons and savage yells told, as the emigrants supposed, the nature of the secret foe. A scene of terror and confusion indescribable must have followed this attack, as the train realized the effects of the first fire and saw the peril of the situation, but those Arkansas men were brave and heroic, and they soon had their long rifles in hand and drove the murderous assailants from the gulch to a more distant place of concealment. Then the besieged emigrants began to fortify their position. The wagon wheels were chained together, a ditch dug for the riflemen and to protect the women and children, and Capt. Fancher arranged his forces for the battle which he knew had only begun. The Indians kept up the fire from their new position, which the emigrants returned from time to time when they saw a good chance to do effective work. The dead were buried, uncoffined, in rude graves dug within the corral, and the wounded received such attentions as the situation would allow. Thus the first day of the siege wore on while the savage enemy received new recruits from the surrounding mountains. The first attack had stampeded the cattle and the Indians drove off the animals and butchered some of them in sight of the emigrants. Night came and brought new fears and perils to the beleagured train. There was no sleep during the long, terrible hours till the dawn of the second day of the siege. All night the Indians had feasted and yelled around the camp and by morning they could be seen in larger numbers. It was evident that other tribes were joining the cruel Utes in their blood-thirsty war on the emigrants. The men of the train saw the increasing danger of their situation and resolved to try to reach aid by sending two trusty messengers to the Mormon settlement at Cedar City. The men started on their perilous trip and the emigrants fiught on and waited for help. That night while the two scouts were telling their sad story to some of Brigham Young's disciples at Richard's Spring and begging for assistance one of the men, Adam [sic - Aden?], was shot and killed by a Mormon assassin, and the other messenger, though wounded, made his escape back to the Meadows and disclosed to his companions the awful truth that the Indians were but the allies of the whites in the attack on the train. Hope must have died in the hearts of the weary and doomed emigrants when they learned that the Mormons were aiding the savages. Soon they saw the story of their wounded messenger confirmed when white men appeared among the war-paonted Indians and became open and active allies of these howling fiends. These inhuman fanatics of the Mormon faith were signaled by the people in the camp, but they refused to recognize a flag of truce even when carried by a little child. One last effort to reach some friendly hand beyond the besieging foes was made. A statement of the condition of the train was set forth in writing, addressed to Masons, Odd Fellows, Methodists, Baptists and all humane people. This was signed by the emigrants and given to three of the most active and resolute men in the camp with instructions to go westward in search of help. There was no hope of aid from the other end of the route, as the fate of Aden had already shown. The three messengers stole out of the corral at night and started on their mission. They were pursued, overtaken in the Santa Clara Mountains and all slain. The cowardly foes hung around the camp day and night, firing whenever they could see one of the emigrants. If a man, woman or child left the corral to go to the spring or to get firewood a shower of bullets fell around the exposed person. Hunger and thirst wwere added to the miseries of the camp and the stench of the putrefying carcasses of horses and cattle killed on the first day of the fight poisoned the air. The days and nights came and went, but no sign of relief or mercy could be duscerned by a member of the train. The tragedy that began on Monday morning was soon to end with a scene of horror which would give to the Mountain Meadows a name unparalleled in the catalogues of great crimes. To show how the emigrants were butchered by the treacherous Mirmons who led the Indians in this most atrocious massacre let the Mormon bishop John D. Lee, who wrote his confession under sentence of death, tell the sickening story. It was about daylight Friday morning, the fifth day of the siege, when a council was held by the Mormons taking part in the fight decided that the emigrants must be decoyed out of their camp and then murdered. Lee says about the massacre: "The emigrants had kept a white flag flying in their camp ever since they saw me cross the valley. Bateman took a white flag and started for the emigrant camp. When he got about half way to the corral, he was met by one of the emigrants, that I afterwards learned was named Hamilton. They talked some time, but I never knew what was said between them. Brother Bateman returned to the command and said that the emigrants would accept our terms * * * The present survivors of the Mountain Meadows massacre now claim a mention in this story. The children were raised in Northwest Arkansas and Southwest Missouti by their kindred and friends. Some of them died before reaching the years of maturity. The surviving members of the little band, orphaned so cruelly, shared the common lot of the young people of the Ozark country. The[y] worked at rural avocations, attended such schools as the White River region afforded a few weeks each year, learned the practical ways of life through some hard experiences, loved, wedded, and became, as a rule, the heads of numerous families. Tryphena Fancher, the only daughter of Capt. Fancher, whom the Mountain Meadows murderers spared, is now Mrs. J. C. Wilson, and lives on Osage Creek, eleven center of Carroll County, Ark. She is a pleasant, motherly woman, about 41 years old, and has nine children. Mrs. Wilson's husband is a well-to-do farmer and stock raiser. In speaking of her family and the massacre this only heir now left to cherish the memory of the brave commander of the butchered train, says: "I am the youngest daughter of Capt. Alexander Fancher. My mother's name was Eliza. I had three or four sisters and four brothers. I do not know the names of any of them, except my oldest sister, Mary, and my youngest brother, Kit Carson, who was rescued with me and brought back to Arkansas. Kit died eighteen years ago. I do not know how old my people were when killed. My father was about 40, I think. Kit and I were the only members of our family spared. I do not remember anything about the massacre or our stay with the Mormons. The first thing I can remember was seeing was sseing the lake. The next thing I recollect was our arrival at Carrollton when brought home. I do not call to mind any incident that occurred on the way home. Kit and I were taken and kept by John D. Lee. Kit was two years younger than me." Milum Tackett, one of the two survivors taken to Washington City, lives about fifteen miles from Berryville, Ark., and is the father of a large family. He remembers some of the incidents of the trip to Utah and much about the massacre. He says that a distinct picture of the fight with the Indians and Mormons, which has always been in his mind, was the heroic part taken by his aunt, Mrs. Jones, who fought with the men after the first attack on the train, the courageous woman using the gun of one of the fallen emigrants. During the butchery of the people after the surrender the little fellow thought he was to be killed and ran to a white man and begged for mercy, offering to give the Mormon, as a reward for his life, a new coat much prized by the boy. Milum Tackett returned to the West after he grew to manhood and revisited, it is said, the fatal Meadows, the only one of the survivors who has ever beheld the scene of the massacre since the awful day of death. William Tackett, the other member of that family spared, some two years younger than Milum, died near Proteus, Taney Co., Mo., in the summer of 1893. His grave in the lonely cemetery near White River is marked by a tomb stine bearing the inscription: "One of the survivors of the Mountain Meadow Massacre." This grave always attracts the attention of strangers, and all the children throughout the country can tell every word of the inscription. William Tackett left a wife and five or six children, who a short time ago moved to Orange City, Cal. The Baker children were raised near Harrison, Boone Co., Ark. Sarah married J. A. Gladen, and has to-day seven children, one of whom took the premium at a baby show in Harrison several years ago. Mrs. Gladen remembers but little, if anything of the killing of her parents and one suster at the massacre. She tells this story for the Sunday Post-Dispatch: "My father's name was George W. Baker, and my mother's name was Marvena. I have but a very faint recollection of the murder of our people at the Mountain Meadows. There is a hole through the lower part of mt left ear which I suppose was made by a bullet, but I do not remember being shot. My sister, Martha, says that I was sitting on father's lap in the camp when I received the wound in the ear. Our sister, Vina, was never heard of after the massacre, but Martha says she saw men leading her away about the time the murdering stopped. She thinks that Vina was spared. I have some recollection of living with the Mormons. They did not violently abuse us, but we were poorly fed and clothed. They sold us from one family to another. They dod not allow the children to stay together, but kept us mostly in separate families." William Baker lives near Harrison, and is a prosperous farmer. Fannie Dunlap married a Linton, and her Post-office is Valley Springs, Boone County, Ark. The other survivors are scattered, Texas being the home of one or two of them. William C. Mitchell, the man who went to Fort Leavenworth after the children, has been dead for many years. Mrs. Railey, the woman that assisted in bringing the survivors home, now lives near the "Old Camp Ground," three miles from Lead Hill, Boone County, Ark. She is a very old lady and the event of her life was that trip to Fort Leavenworth and back when the rescued little ones were returned to their relatives. Mrs. Railey always speaks of the survivors as "my children," and the aged lady tells many interesting stories of that memorable journey from Fort Leavenworth to Carrollton, Ark., with the orphan band. She has always desired to have a reunion of the Mountain Meadows survivors, but could never get the "children" together. Note 1: James "Polk" Fancher's efforts in organizing a reunion for the 1857 massacre survivors seem to have have been brought to fruition by James Lynch, one of the heroes of their 1859 rescue in Utah. The following news item appeared in the New York Times of Oct. 10, 1893: "A reunion of the survivors of the Mountain Meadow massacre is to take place here [at Harrison, Ark.] this week. James Lynch of Washington, represents the survivors in a suit against the United States, and he reached Harrison a day or two ago. The massacre occurred in September, 1857, and only fifteen children escaped death, ten of whom are now living, five of them in Boone county. -- Capt. Lynch says the Mormon Church has been sued for $256,000, and that the case is likely soon to be settled in favor of the plaintiffs. The wagon train had $70,000 in money, and $26,000 in cattle, besides household effects. -- Capt. Lynch was in the United States Army and assisted at the rescue. He has since devoted almost his entire attention to the survivors." Note 2: Despite newspaper notices, no documented evidence for a 1893 survivors' reunion has yet been located. Possibly the reunion was postponed for two years -- a page in the Sept. 19, 1895 issue of the Fort Worth Gazette reprinted the lengthy St. Louis Post-Dispatch article, with no mention of an 1893 meeting. |

|

(view images from this Aug. 25, 1940 A.W. article: No. 1 | No. 2 | No. 3 | No. 4

|

|

|

Back to top of this page

History Vault | Bookshelf | Spalding Library | Mormon Classics | Newspapers

HOME unOFFICIAL JOSEPH SMITH HOME PAGE CHRONOLOGY

last updated: Mar. 13, 2010

"CHILDREN OF THE MASSACRE"

"CHILDREN OF THE MASSACRE"

I SURVIVED

I SURVIVED